A recently uncovered 180-ton green stone in eastern Kyrgyzstan has triggered renewed international interest not only because of its extraordinary size, but also due to the deep historical and cultural associations such stones have carried across Eurasia for millennia.

While scientific analysis has identified the stone as a lower-grade variant known as nephritoid, its discovery has opened up broader discussions that reach far beyond geology, bringing ancient belief systems, ritual practices, and sacred landscapes of both early Turkic societies in Central Asia and the Hittite civilization in Anatolia back into focus.

The massive stone was uncovered near the village of Chon Kyzyl Suu in the Jeti Oguz district of the Issyk Kul region, an area already known for its striking natural landscape. Local residents were the first to bring the monolith to light, after which specialists were sent in to examine its structure and composition.

Experts determined that the stone closely resembles nephrite, a type of jade long valued for its durability and aesthetic appeal, but clarified that it is technically nephritoid. This mineral is visually similar to nephrite yet considered one grade lower in quality due to differences in density and purity. Despite this distinction, specialists emphasized that the stone holds considerable visual and geological value and represents an important example of the region’s natural heritage.

Local authorities and residents are now preparing to put the site on the map as a cultural and nature-based tourism destination, with expectations that the sheer scale of the monolith will draw both domestic and international visitors to Issyk Kul.

The discovery has also revived interest in ancient Turkic beliefs surrounding stones believed to influence natural forces. In pre-Islamic Turkic tradition, nature was understood through sacred elements, particularly mountains and trees, which were seen as central to the creation of the universe and the protection of the state.

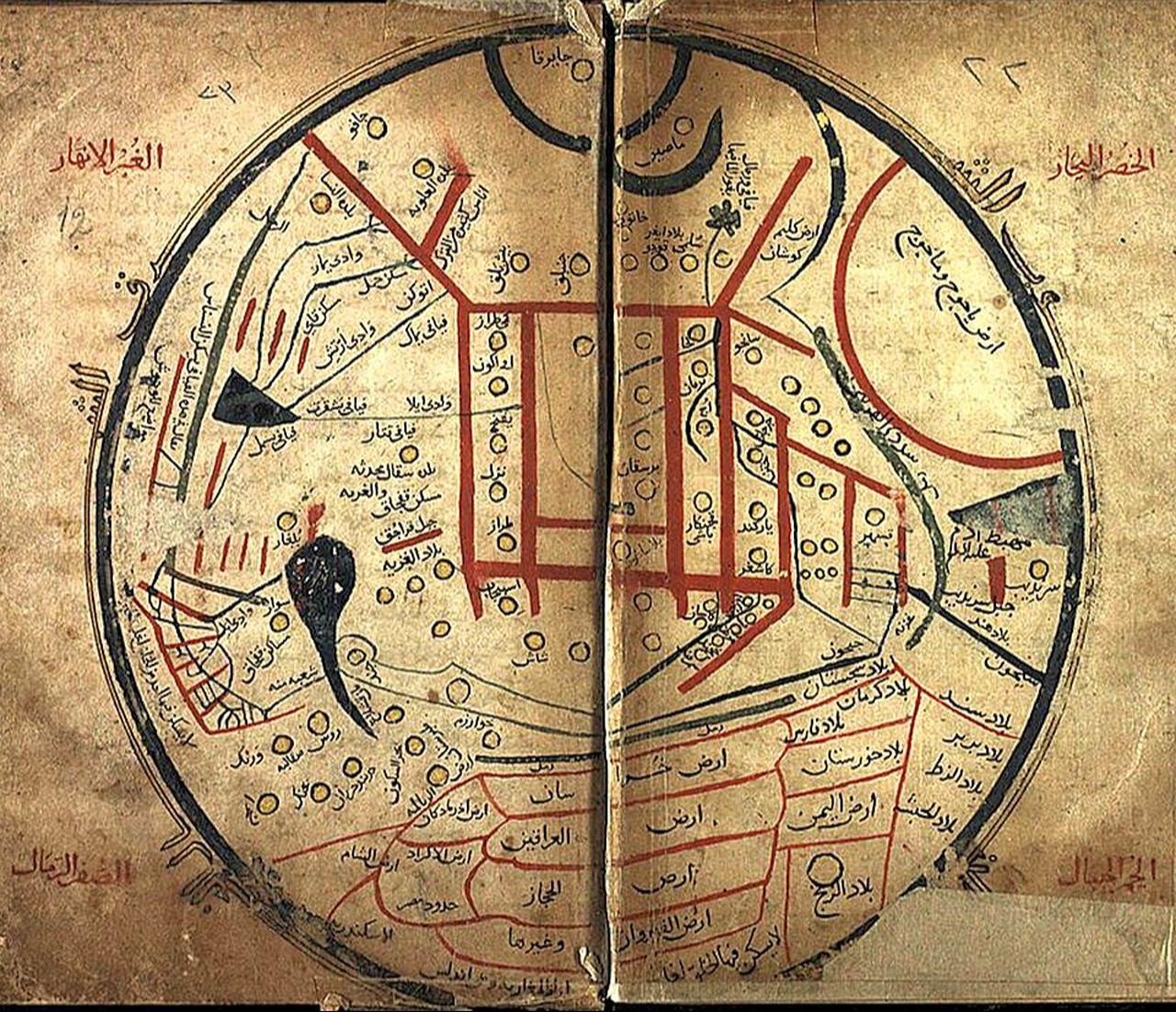

Within this worldview, a legendary object known as the Yada (jade) stone, referred to in Arabic sources as hacer al matar, occupied a special place. Medieval sources, including the renowned lexicographer Mahmud al-Kashgari, described the Yada stone as an object used in ritual practices to call down rain, snow, or wind, particularly during droughts or forest fires. Kashgari recounted witnessing such a ritual in the lands of the Yagma tribe, where snowfall was said to have extinguished a summer fire.

These beliefs were closely tied to the Turkic tree cult. Sacred forests such as Otuken were viewed as the spiritual heart of political authority, and rulers were believed to secure the survival of their realm by maintaining harmony with nature. Trees were planted at graves, dynasties traced their origins to mythical trees, and rituals involving stones and weather were seen as extensions of this natural order.

A strikingly different yet comparable case can be found in Anatolia, in modern-day Türkiye, at the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa. Within the ruins of the Great Temple stands a large, cube-shaped green monolith carved from serpentine or nephrite-like stone. Known locally as the “wish stone,” its original function remains unresolved.

According to excavation director Professor Andreas Schachner, the stone differs markedly from surrounding materials, although the mineral itself is locally available. Archaeological evidence indicates that the monolith was not used in its current position during the Hittite period, as it lies well below the original walking level. The site continued to be used as a settlement and cemetery after the fall of the Hittite Empire, further complicating efforts to date or contextualize the object.

Various theories have been put forward, ranging from a ritual altar to a ceremonial seat or an object linked to the Hittites’ well-documented interest in astronomy and seasonal cycles. However, no definitive evidence supports any single interpretation, and researchers caution that its purpose may never be fully understood.

While there is no direct historical link established between the Turkic Yada stone traditions and the Hittite green monolith, both cases reflect how stone objects could take on symbolic or sacred roles within societies deeply attuned to nature. In both Central Asia and Anatolia, green stones associated with durability and the earth appear within religious or ritual landscapes, even when their precise functions remain unclear.