For centuries, the Ottoman Empire stood as one of the world’s most powerful political entities. Yet its strength was not defined solely by military victories or territorial reach. It was also measured by its ability to absorb the displaced, protect the persecuted, and transform forced migration into social stability. From Spanish Jews fleeing the Inquisition to Muslims and Christians escaping Russian expansion, Ottoman lands became a refuge not by chance, but by policy, confidence, and imperial self-assurance.

Unlike early modern nation-states that equated unity with exclusion, the Ottoman Empire ruled through inclusion. Migration was not seen as a burden, but as an opportunity to reinforce the empire’s demographic, economic, and cultural vitality.

The expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 marked one of the greatest forced migrations in European history. Following the Alhambra Decree, Jews were given a brutal ultimatum: Conversion or exile. Tens of thousands chose exile and found no welcome in Christian Europe.

The Ottoman response was decisive and confident. Sultan Bayezid II dispatched imperial ships to rescue Sephardic Jews from Iberian ports. Refugees were encouraged to settle in Istanbul, Thessaloniki, Edirne, and Bursa.

Historian Halil Inalcik, as cited by Salahi R. Sonyel’s article, emphasized that the Ottomans made little distinction between persecuted Jews and Andalusian Muslims. Both were viewed as victims of a hostile rival power. By sheltering them, the empire asserted both moral authority and geopolitical confidence.

The demographic impact was immense. Sephardic Jews soon constituted nearly 90 percent of the empire’s Jewish population. Istanbul became home to the largest Jewish community in the world, while Thessaloniki emerged as a predominantly Jewish city.

The Ottomans did not merely shelter refugees; they empowered them. Spanish Jews brought advanced skills in trade, medicine, diplomacy, and technology. In 1493, brothers David and Samuel ibn Nahmias established the empire’s first printing press in Istanbul, a development highlighted in a 1992 study in Belleten by Salahi R. Sonyel.

This openness reflected imperial self-confidence. The Ottomans did not fear difference; they regulated it. Jewish communities were granted autonomy over education, courts, and religious life under imperial protection. As Sonyel notes, this autonomy allowed Jewish culture to flourish while remaining loyal to the state.

In his 16th-century chronicle Seder Eliyahu Zuta, Elijah Capsali remarked that Spain had weakened itself by driving out productive citizens, a view later reinforced by historian Mark A. Epstein, who argues that Ottoman tolerance functioned as calculated statecraft rather than simple generosity.

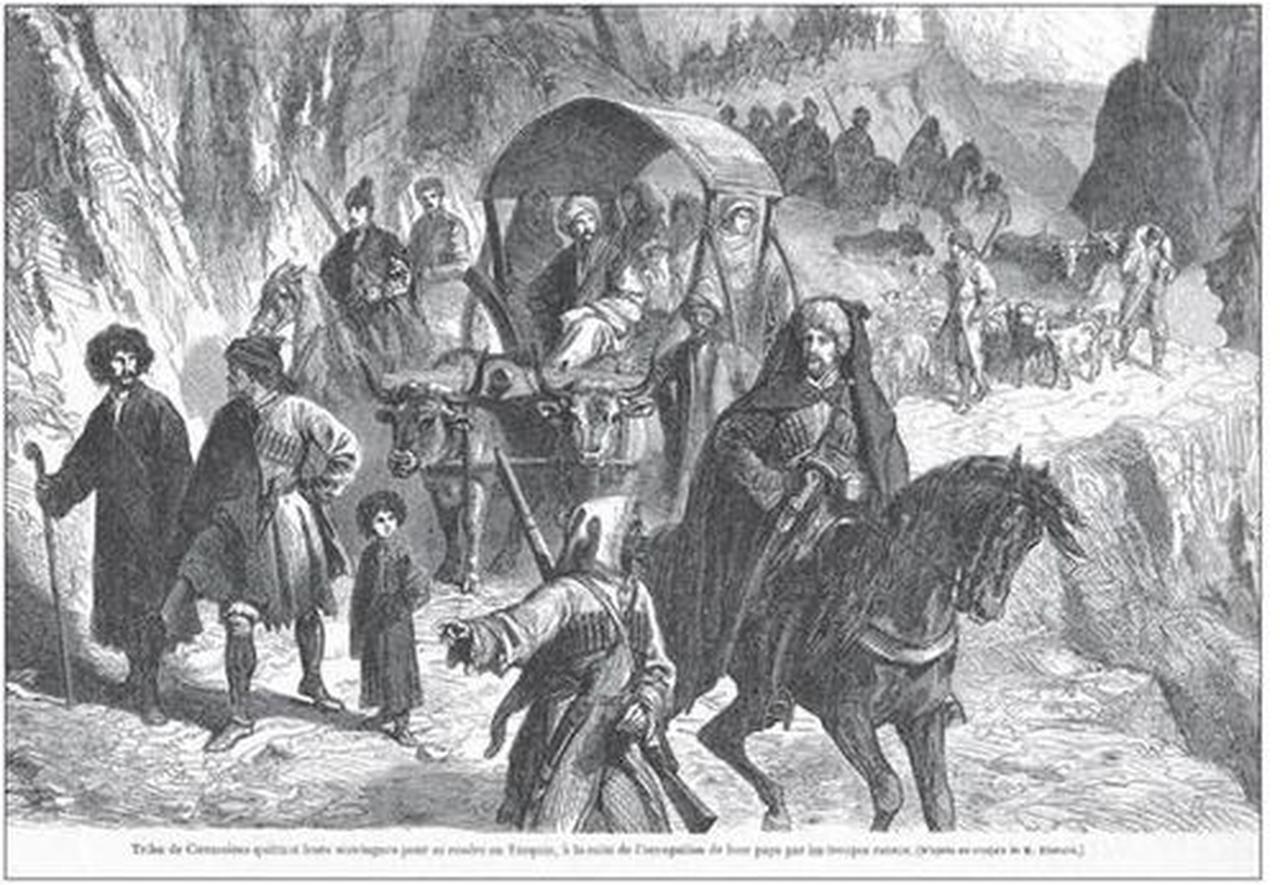

Ottoman hospitality was never limited to Jews or Muslims. From the late 18th century onward, Russian expansion triggered mass displacement across the Black Sea and Caucasus regions. According to Ekrem Bugra Ekinci, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the Caucasus, hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatars, Circassians, and Chechens fled to Ottoman lands.

These migrations intensified during the Crimean War and later conflicts. Despite economic strain and territorial losses, the Ottoman state continued to accept migrants, settling them across Anatolia and the Balkans.

Christian refugees also found shelter. Cossacks fleeing Tsarist religious reforms were settled in western Anatolia, while Molokans, persecuted for their beliefs, were welcomed in Kars. Later, after the 1917 Russian Revolution, nearly 200,000 White Russian refugees arrived in Istanbul and Gallipoli, even as the empire itself reeled from World War I.

According to “The Ottoman Empire: A Shelter for All Kinds of Refugees,” even figures such as Leon Trotsky were granted temporary refuge, an act reflecting Ottoman adherence to long-standing asylum traditions.

One of the empire’s most distinctive migration policies was rooted in Islamic law: Aman, or guaranteed protection. According to M. Yakub Mughul, his research examines how this legal framework ensured security and recognized status for non-Muslims while placing them under imperial authority rather than exclusionary rule.

Historians note that the Ottoman reception of refugees was grounded in this concept, which extended state protection to non-Muslims while allowing them to retain their religious and communal identities. Unlike modern asylum systems, aman did not presume permanent foreignness; instead, it enabled integration within the imperial order without enforced marginalization.

Under aman, migrants’ lives, property, and families were legally protected. Refugees could move freely, engage in trade, and establish communal institutions, gradually acquiring permanent status. This framework fostered integration rather than isolation, reinforcing loyalty to the Ottoman state while preserving social pluralism.

According to historian Vladimir Hamed-Troyansky, the scale of nineteenth-century refugee flows from the Russian Empire pushed the Ottoman state to institutionalize migration management, leading to the establishment of the Muhacirin Komisyonu (Commission for Immigrants) in 1860.

Circassians were placed in Uzunyayla and Sivas, Crimean Tatars in Konya, and Caucasians across Central Anatolia. Housing, food, medical care, and transportation were state-funded. Refugees were not left in camps indefinitely; they were turned into producers.

Perhaps the most powerful demonstration of Ottoman sovereignty was its refusal to surrender refugees, even under diplomatic pressure. As Ekinci recounts, the empire risked war rather than hand over asylum seekers, including Swedish King Charles XII and Hungarian and Polish revolutionaries after 1848.

This policy signaled strength. Protection was not conditional on religion, ethnicity, or political convenience. It was a declaration of imperial dignity.

The Ottoman Empire’s approach to migration reveals a fundamental truth: Hospitality is not weakness. It is an extension of power. By transforming refugees into citizens, contributors, and allies, the empire turned displacement into durability.

As historian Isabelle Poutrin notes in “The Refugee Crises of the 16th and 17th Century,” while Europe expelled, the Ottomans absorbed and endured.

In an age of walls and exclusion, the Ottoman experience stands as a reminder that confidence, law, and compassion can coexist, and that empires are remembered not only for whom they conquered, but for whom they protected.