Kafkas University scholar Ekin Akturk presents a focused study of the Sari Kiz (Blonde Girl) legend—an Anatolian narration rooted in Kaz Daglari (known in antiquity as Mount Ida)—showing how a single story has moved through time, place, and belief to shape cultural memory across Türkiye.

The study, delivered at the International Scientific Symposium “Epic and National Identity” in Bishkek on Feb. 28, 2025, maps how six closely related variants have been told and retold and explains why communities continue to pass them down.

Drawing on foundational folklore scholarship, the paper recalls that the Grimm Brothers described legends as reports—true or untrue—about specific persons and events. Max Luthi framed legend as a narrative form that, in an emotional register, claims to relate real occurrences and is transmitted orally across generations.

Linda Degh defined legend as a traditionally shaped story told to third parties and set in a historical past; it is not fact, yet the teller and listeners treat it as if it were true.

In Türkiye, researchers such as Ziya Gokalp, Pertev Naili Boratav, Ali Berat Alptekin, Saim Sakaoglu, and Bilge Seyidoglu helped build the field and outlined local classifications.

The paper restates a widely used grouping: legends about the end and creation of the world; historical legends; legends tied to the origins of specific natural places; legends about supernatural persons and beings; and religious legends. It stresses that legends unfold in the recognizable “today’s world,” which marks them off from myth.

Sari Kiz sits at the intersection of landscape and faith. Set on Mount Ida, the legend centers on a young woman and themes of love, slander, sacrifice, and the force of nature. Local transmission has kept it alive among communities linked to the mountain.

The study notes that Sari Kiz is counted as a saintly figure in Shia-leaning belief and that tellings among Yoruks connect the story to Ali. It highlights the continuing importance of the Tahtaci Turkmens, who regard the mountain as sacred and maintain rites that draw on hearth, mountain, and tree cults within the Alevi-Bektashi tradition.

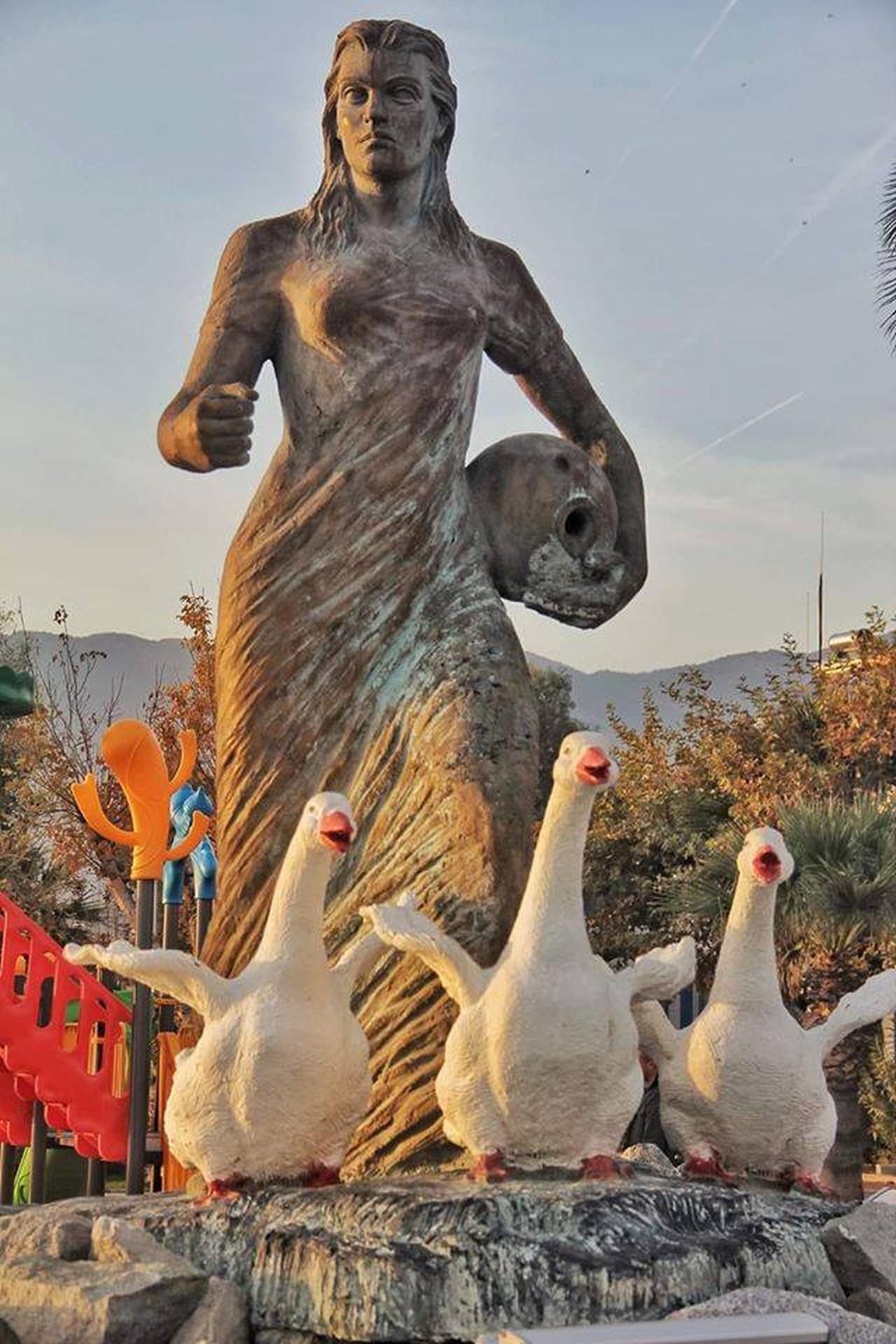

Although details shift, the narrative core remains stable. A strikingly beautiful daughter faces slander; her father, unable to kill her, leaves her with geese high on Mount Ida. She survives and performs marvels—lighting the peak, turning storm to springlike calm, or drawing water from the Edremit Gulf for ritual ablution.

The father dies nearby, and place-names emerge: Sarikiz Tepesi and Babatepe.

Other variants keep the same arc while adding distinct motifs. One version features a youth who drowns under salt sacks; another recounts a public shaming by eggs that turn her yellow, fixing the name Sari Kiz. Notable direct speech appears in two tellings: “I cursed Edremit so that its geese would be fatty and its girls would be lovestruck,” and the cry “Ak cay!” that releases a stream, echoed in the place-name Akcay.

The study also records readings that link the figure to Christian tradition and even to Aphrodite, underscoring how the Ida/Kaz landscape has long hosted layered sacred meanings.

By pairing story elements with named locations—Edremit, Gure, Akcay, Sarikiz Tepesi, Babatepe—the legend binds moral lessons to the terrain.

The paper presents Kaz Daglari as both stage and symbol: a site once called Ida in classical sources and now a mountain range in Balikesir province, where the narrative and the ritual practices that accompany it reinforce local identity.