Two archaeological sites—Arslantepe in Türkiye and Tell Hisban in Jordan—have become central to a research project examining how engaging local communities in archaeological work can strengthen their sense of identity and connection to their land. The study, conducted by Ilda Faiella, a Ph.D student in Heritage Science at Sapienza University of Rome, compares these two culturally distinct but structurally similar locations to understand the potential of community archaeology in linking heritage to everyday life.

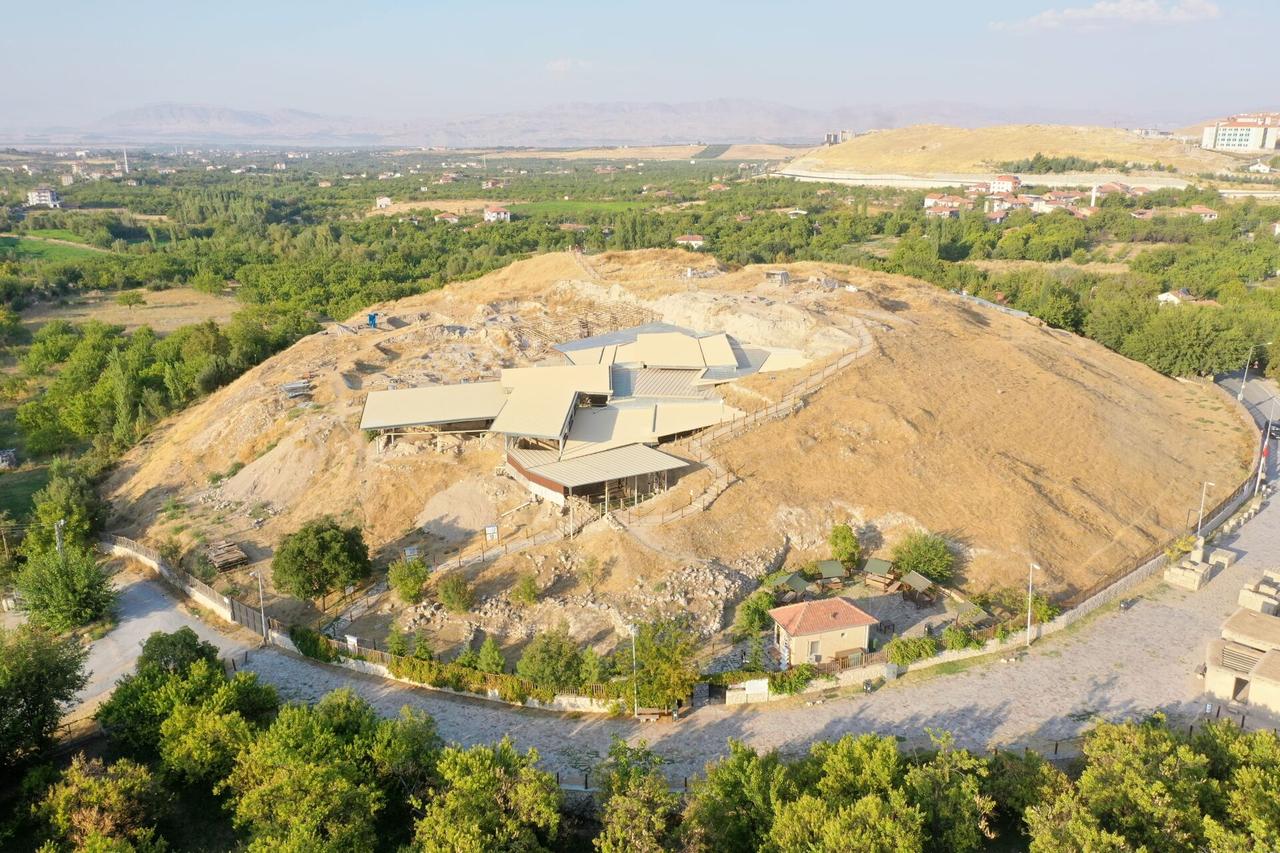

Arslantepe, located near the village of Orduzu in eastern Türkiye, has been excavated for over 60 years by Sapienza University of Rome. The site includes a monumental palace dating to the 4th millennium B.C., one of the oldest in the Mesopotamian world. Tell Hisban, near Amman in Jordan, has been studied since the 1960s by Andrews University in the United States. It includes remains from the Iron Age through the Ottoman period.

The research involved interviews with men and women aged between 10 and 90 living within roughly 1.5 kilometers of each site. It found that the sense of connection to the archaeological sites decreased as distance from the sites increased. This spatial factor was especially visible in Arslantepe, where those living farther from the site felt more detached from its cultural importance.

In Hisban, residents demonstrated deeper engagement with the site, supported by community-driven initiatives led by local organizations like SELA and long-term collaboration with archaeologists. These efforts have led to the formation of associations such as the Committee for Tourism and Heritage and a local Women’s Center, both actively contributing to the site’s preservation and promotion.

In contrast, community involvement in Arslantepe remains more limited. While male villagers often work on excavation teams and see the site as a source of income, the participation of women has been minimal. Despite expressing interest, many women lack access to inclusive engagement opportunities.

Both Orduzu and Hisban maintain traditional customs and crafts that offer important links to the past. In Orduzu, mudbrick homes and traditional ovens, such as ocak and tandir, remain in use and reflect architectural similarities with the ancient palace complex at Arslantepe. In Hisban, community values such as hospitality and cultural continuity through local customs remain strong.

Residents in both areas recognized archaeology’s educational and economic potential. However, frustrations exist. In Hisban, many expressed disappointment at the limited economic returns from archaeological tourism and excavation work, which has recently been reduced to a brief two-week period every two years. In Orduzu, while local men benefit from seasonal employment, the benefits remain short-term and unequally distributed.

A key finding of the study was the need for more transparent and accessible communication between archaeologists and local populations. In both villages, residents expressed a desire for clearer information about excavation activities and their significance. This was especially strong in Hisban, where there were calls for knowledge-sharing platforms in the local language.

In Orduzu, long-term collaboration has built strong relationships with some families, particularly among older men who have worked alongside researchers. However, that trust does not extend evenly throughout the village, especially to younger and more distant residents. In Hisban, relationships with archaeologists have weakened due to less frequent fieldwork, impacting community involvement.

The research proposes several strategies to build stronger community bonds through archaeology:

The study concludes that local people should not merely observe history being uncovered—they must be part of shaping how that history is understood and preserved. By redefining the relationship between communities, archaeological sites, and research teams as a collaborative partnership, cultural heritage can serve as a dynamic force for identity, sustainability, and resilience.