On a humid July afternoon in the northwestern Turkish city of Edirne, men step barefoot onto a grass field darkened by olive oil, sweat and rain.

Their bodies glisten under a hazy summer sky.

Drums beat. Prayers are murmured. Then, with a sudden lunge, two wrestlers lock arms and begin a slow, deliberate struggle that can last minutes or hours.

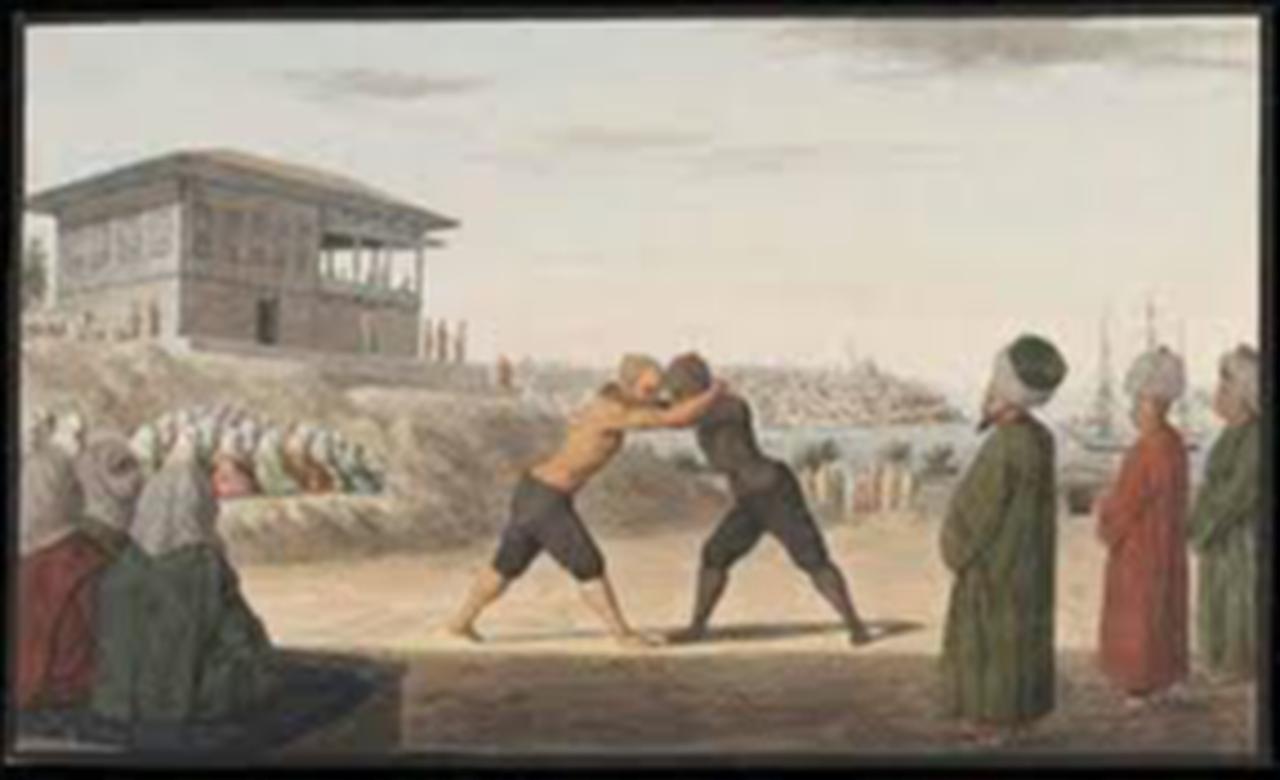

To an untrained eye, Türkiye’s oil wrestling, known as yagli gures, may look like a test of raw strength.

But to those who gather each year for the Kirkpinar Oil Wrestling Festival, it is something more enduring: a ritualized performance of history, faith, and national identity that has survived for over seven centuries.

Recognized by UNESCO in 2010 as part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage, oil wrestling occupies a singular place in Türkiye’s cultural landscape.

Its most important stage, Kirkpinar, is widely regarded as the world’s oldest continuously held sporting competition, with origins dating to the 14th-century Ottoman frontier.

Held annually in Edirne, the festival is not merely a sporting event but a living archive of how physical culture, religion, and state power have long been intertwined in Turkish history.

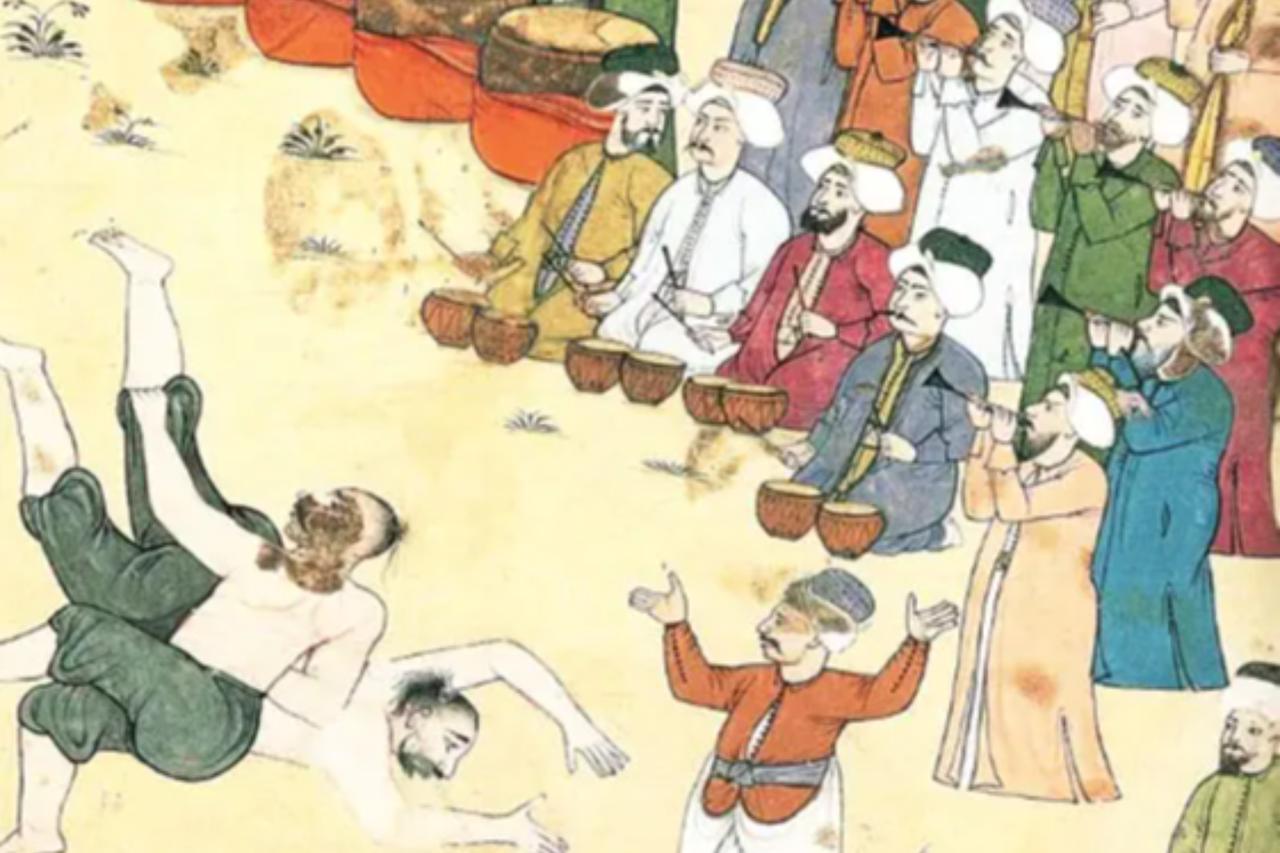

Wrestling among Turkic peoples predates both the Ottoman Empire and the modern Turkish Republic.

Long before their conversion to Islam, Turkic communities practiced wrestling as a form of physical training and moral education.

Early historical accounts describe matches held near the graves of fallen warriors, lasting days and nights, where remembrance and endurance merged.

After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which opened Anatolia to Turkic settlement, these traditions migrated west. Birgit Krawietz argues that as Islam became central to social life, wrestling absorbed new ethical frameworks.

Historian Eugeniy Bakhrevskiy highlights how Dervish lodges, or tekkes, established by figures such as Haci Bektas Veli and Sari Saltuk, became key spaces where bodily discipline and spiritual instruction intersected.

It was within these religious and social institutions that oil wrestling took shape, not as an unregulated contest, but as a practice governed by codes of conduct. Strength alone was insufficient.

Wrestlers were expected to demonstrate humility, patience, and respect, reflecting broader Islamic ideals of self-control.

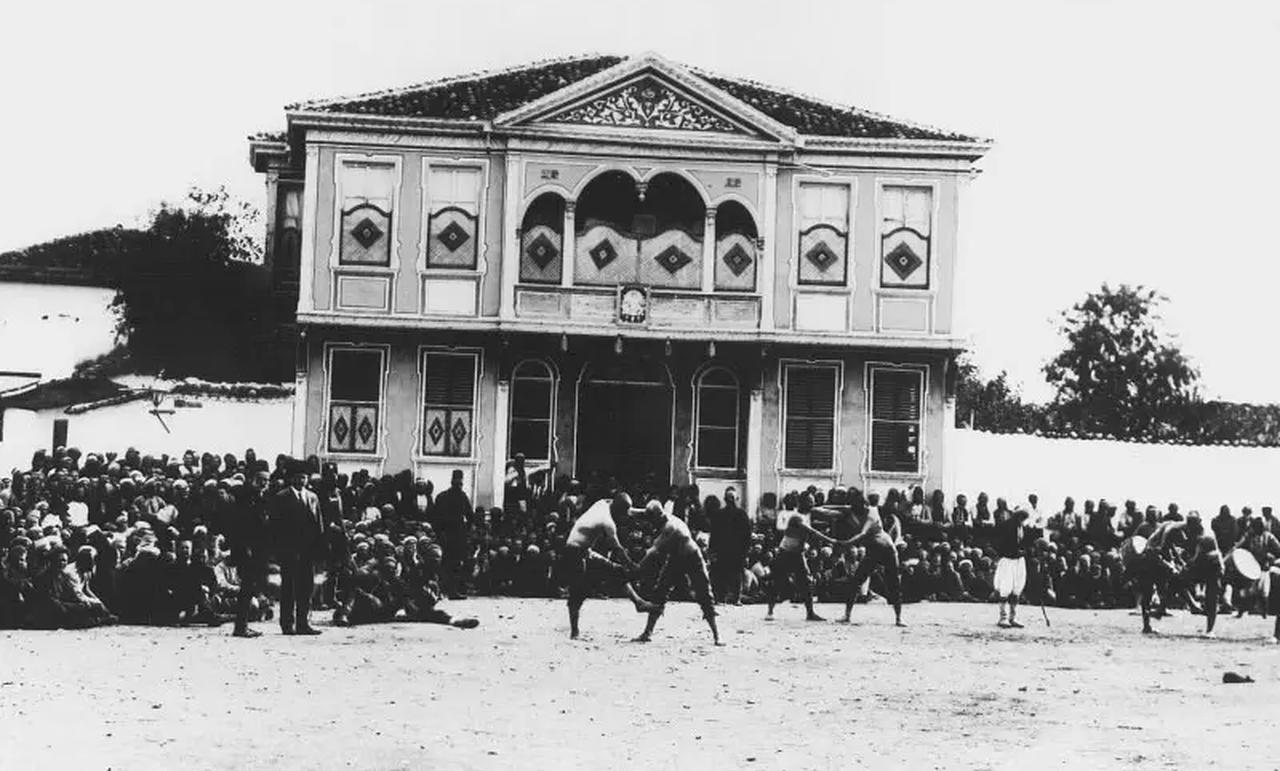

By 1362, Kirkpinar had become a fixture near Edirne, then a major Ottoman city. Over the centuries, the festival endured imperial expansion, military defeat, regime change, and sweeping modernization reforms.

It survived the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of a secular republic determined to redefine Turkish identity.

Today, Kirkpinar appears both ancient and unmistakably modern. Referees enforce standardized rules.

Corporate sponsors line the field.

Television crews broadcast matches nationwide. Yet the structure of the bouts, the pre-match prayers, and the hierarchy among wrestlers remain deeply rooted in Ottoman-era custom, as Adem Kaya and Siymik Arstanbekov argue.

For competitors, the ultimate honor is to be named baspehlivan, or chief wrestler.

The prize is the Golden Belt, awarded annually.

Winning it three consecutive times grants permanent ownership—an achievement that offers not just athletic prestige, but a form of cultural immortality.

If oil wrestling has a sacred object, it is the kispet: the thick leather trousers worn by wrestlers. Traditionally crafted from water buffalo hide, the kispet is heavy and restrictive, forcing wrestlers to rely on technique rather than speed.

Historically, a wrestler did not simply put on a kispet.

He earned it through years of training and a formal initiation ceremony that included prayers and symbolic gestures rooted in Islamic belief.

The garment represented honor, discipline, and belonging to a lineage that extended far beyond the individual.

Although many of these initiation rituals have faded under modern sporting pressures, the kispet remains a powerful visual symbol.

It signals continuity between past and present, reminding spectators that oil wrestling is not just about winning but about embodying a shared ethical tradition.

Scholars have increasingly interpreted oil wrestling through the lens of furusiyya, the Islamic tradition of martial chivalry that flourished in the medieval period.

From this perspective, oil wrestling is not merely folklore or a nationalist spectacle, but one of the last living expressions of an Islamic martial culture that values restraint as much as power.

This helps explain why oil wrestling has resisted full “sportification.”

Kirkpinar occupies a hybrid space, neither fully modern sport nor untouched tradition. Ritual prayers coexist with time limits. Masculinity is on display but tightly regulated by rules emphasizing respect and self-control.

Victory achieved without honor is widely regarded as hollow.

The physical demands of oil wrestling are severe. Matches are fought on slippery ground, careers are often short, and injuries are common. Yet the er meydani, the wrestling field, operates according to a moral economy as much as a competitive one.

Younger wrestlers show deference to elders.

Defeated opponents are embraced. Unsportsmanlike behavior is discouraged, sometimes publicly. In this world, toughness is inseparable from humility.

Today, oil wrestling stands at a crossroads.

Global media exposure and professionalization have brought visibility and financial support but also risk flattening ritual into spectacle.

Yet its survival across seven centuries suggests an adaptability embedded in its core.

From pre-Islamic steppes to Ottoman dervish lodges, from Edirne’s oil-soaked fields to UNESCO’s heritage lists, oil wrestling has never been static.

It remains what it has always been: demanding, symbolic and stubbornly alive. A tradition that slips from easy definition even as it continues to define Türkiye.