For almost one hundred years, the fez sat at the center of Ottoman public life as a widely shared form of headwear. Before it was swept aside by the hat reforms of the early 20th century, it had worked its way into homes, markets, offices, and even poetry. Historian Professor Ekrem Bugra Ekinci notes that the fez was not simply worn but lived with, shaping etiquette, appearance, and social meaning in ways that are difficult to grasp today.

The adoption of the fez began not as a fashion choice, but as a practical solution. Ottoman naval uniforms required light and agile headgear, and the answer emerged when Grand Admiral Husrev Pasha noticed the fez worn in North Africa, particularly around Tunis. After sailors were equipped with it, Sultan Mahmud II reportedly noticed the new headgear during a ceremonial procession. This moment paved the way for a broader decision: in 1828, the fez was introduced as mandatory attire for soldiers and civil servants, followed by a formal regulation defining its use.

According to Professor Ekinci, the fez did not provoke widespread unrest, contrary to later claims. Because it allowed the wrapping of a turban, it was seen as compatible with religious custom. Contemporary observers, including poet Yahya Kemal, later noted that similar headgear had already been in use among Algerians and shipyard trainees, which eased acceptance. The fez was therefore not perceived as foreign in a disruptive sense, even when worn by the sultan and grand vizier.

As nationalism spread across Europe after the French Revolution, the Ottoman administration pursued the idea of a unified Ottoman identity. In this context, the fez turned into a visual symbol of equality. Regardless of religion, it became the common headgear first of the ruling elite and then of the wider population. Although its name derived from the Moroccan city of Fez, historians point out that its shape resembled the ancient Phrygian cap of Anatolia and that similar forms had circulated across the Mediterranean for centuries.

Even when described as foreign, the fez was not seen as clashing with local custom or belief. Ottoman reforms, as Ekinci underlines, tended to be adapted to the existing social fabric rather than imposed in isolation.

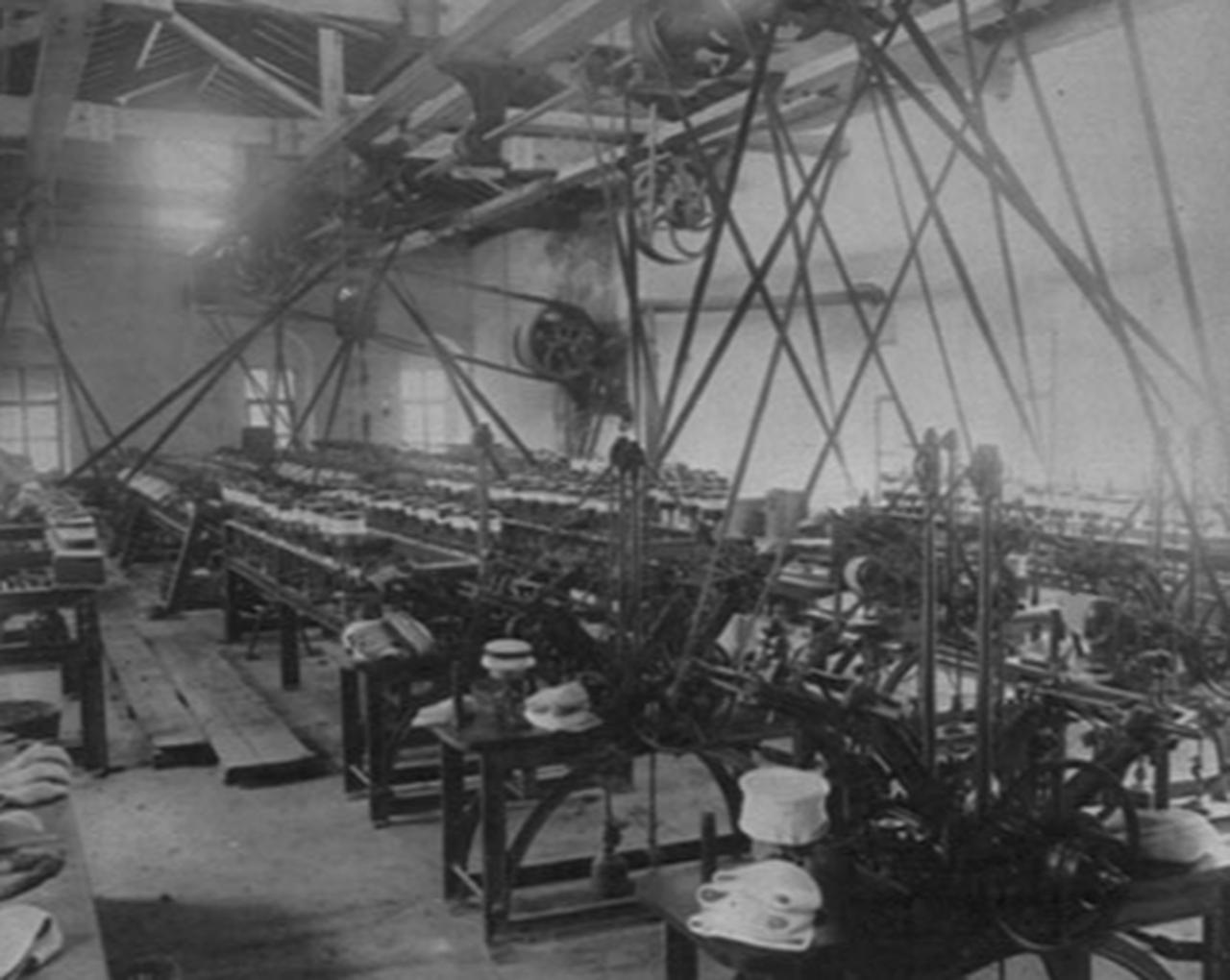

The fez was made from high-quality wool, ideally from merino sheep, because the material held dye well and resisted excessive hardening. Production followed several stages, from knitting and felting to washing, shrinking, shaping, and polishing. As demand grew, imports from Tunisia, Egypt, and Europe were gradually supplemented by local production. The first major factory, the Feshane in Istanbul, opened in the 1830s, while other workshops later appeared in Bursa, Edirne, and Thessaloniki.

Prices varied widely depending on origin and finish, with Tunisian and Egyptian fezzes generally more expensive than European imports. Despite local manufacturing, imports continued to fill the gap. Over time, rules were introduced to distinguish civil servants from ordinary citizens. Civilians were encouraged to wear a plain fez, known as “dalfes,” without additional wrapping, while only religious scholars were allowed white turbans. Public resistance to these distinctions eventually led to more relaxed rules.

Color, shape, and quality communicated social information. Certain shades were associated with specific professions, and poor-quality dye could run in the rain, turning the wearer into a figure of ridicule. Satirical verses and anecdotes circulated widely, reinforcing how closely the fez was tied to public image.

The fez was widely regarded as enhancing male appearance, which explains why it featured so often in poetry, songs, and folk music. Poet Dertli devoted an entire ode to it, while popular songs and regional ballads praised the elegance of the “red-fez youth.” Ottoman women also incorporated a short, decorated fez beneath their headscarves as early as the 16th century, adorning it with gold coins or ornaments.

Social norms reinforced its presence indoors as well. Sitting bareheaded at the table or appearing before elders without a fez was considered improper. At home, some men placed their fez on a mold or shelf and switched to a lighter skullcap, underscoring how central the object was to everyday manners.

Fezzes came in many forms, each with its own name and connotation. Different sultans favored different styles, from the straight-sided Mahmud-style to the shorter Aziz-style and the tapered Hamid-style. The angle at which the fez was worn also mattered. Tilting it slightly to the side was considered elegant, while pulling it too far forward or backward could invite criticism.

The tassel, usually made of black silk and sometimes blue, was a defining feature. Regulations even specified its weight for officials. Its movement, swaying with the wearer’s steps, was seen as a sign of grace. Yet it could also be a nuisance, requiring constant care. Street children earned money by combing tangled tassels, an everyday practice believed to have inspired the expression “puskullu bela,” roughly meaning a troublesome burden.

Some unconventional figures eventually removed the tassel altogether, a gesture comparable to going without a tie in formal dress.

Because fezzes easily lost their shape, an entire profession of mold-makers emerged. Craftsmen used heated wooden or later brass molds to reshape fezzes into standardized forms with names such as Hamidiye or Aziziye, produced in a wide range of sizes.

After the fez was banned, unused molds and remaining examples were preserved. Today, many are held in Istanbul City Museum and Topkapi Palace, offering tangible evidence of an object that once defined public appearance.