To enter the imperial court whether as a grand vizier, a military commander, a palace official, or a foreign ambassador was to step into a world where your clothes announced who you were.

They showed how close you stood to power and how seriously that power took you. Long before fashion was called “soft power,” the Ottomans had mastered clothing as a political tool.

M. Ada Ozdila describes Ottoman governance as a system of symbols and rituals. Justice, architecture, ceremony, and especially clothing worked together to project a divinely sanctioned, orderly empire.

The legal system emphasized order and legitimacy. Court fashion did the same. It made hierarchy visible, wearable, and unforgettable.

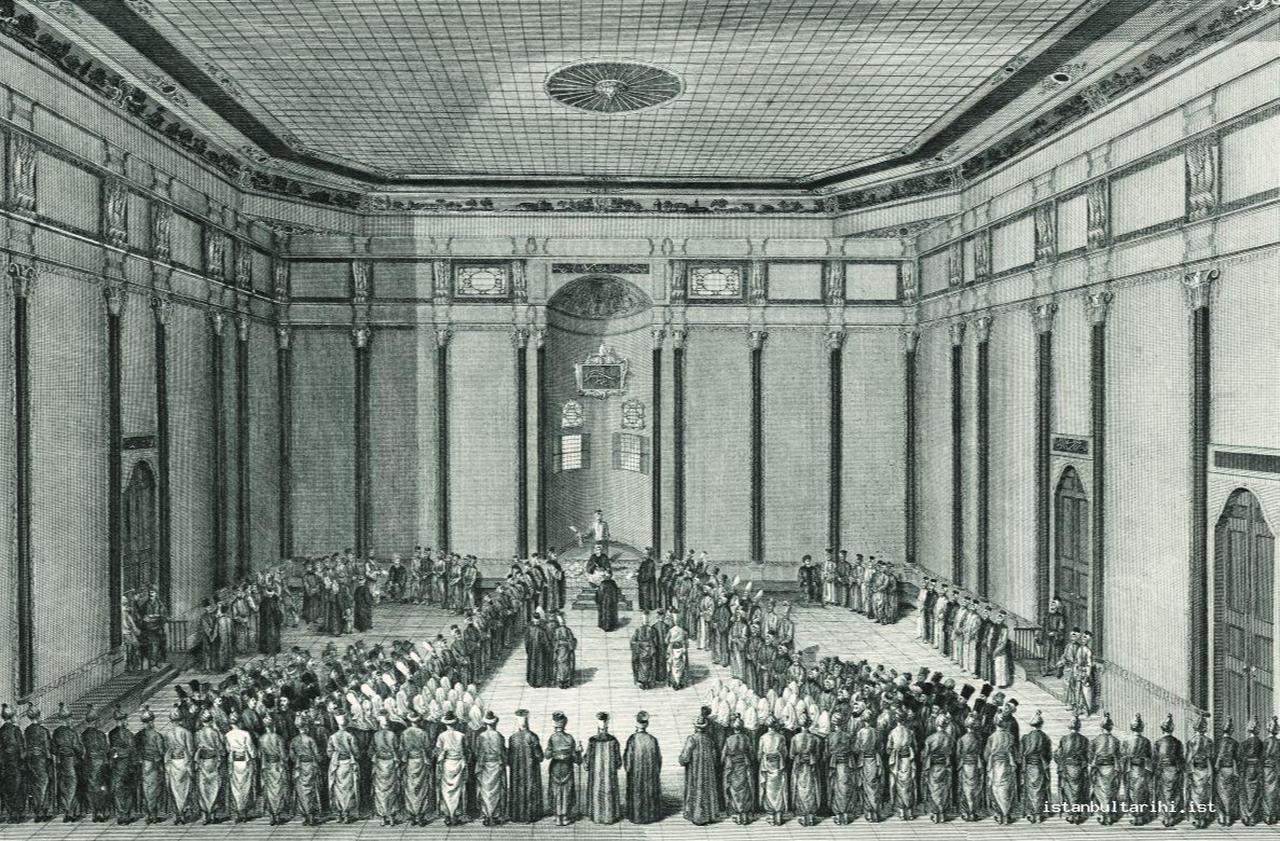

Topkapi was the primary residence of the sultan and the center of government. It housed the imperial court, the sultan’s family, high officials, and administrative offices.

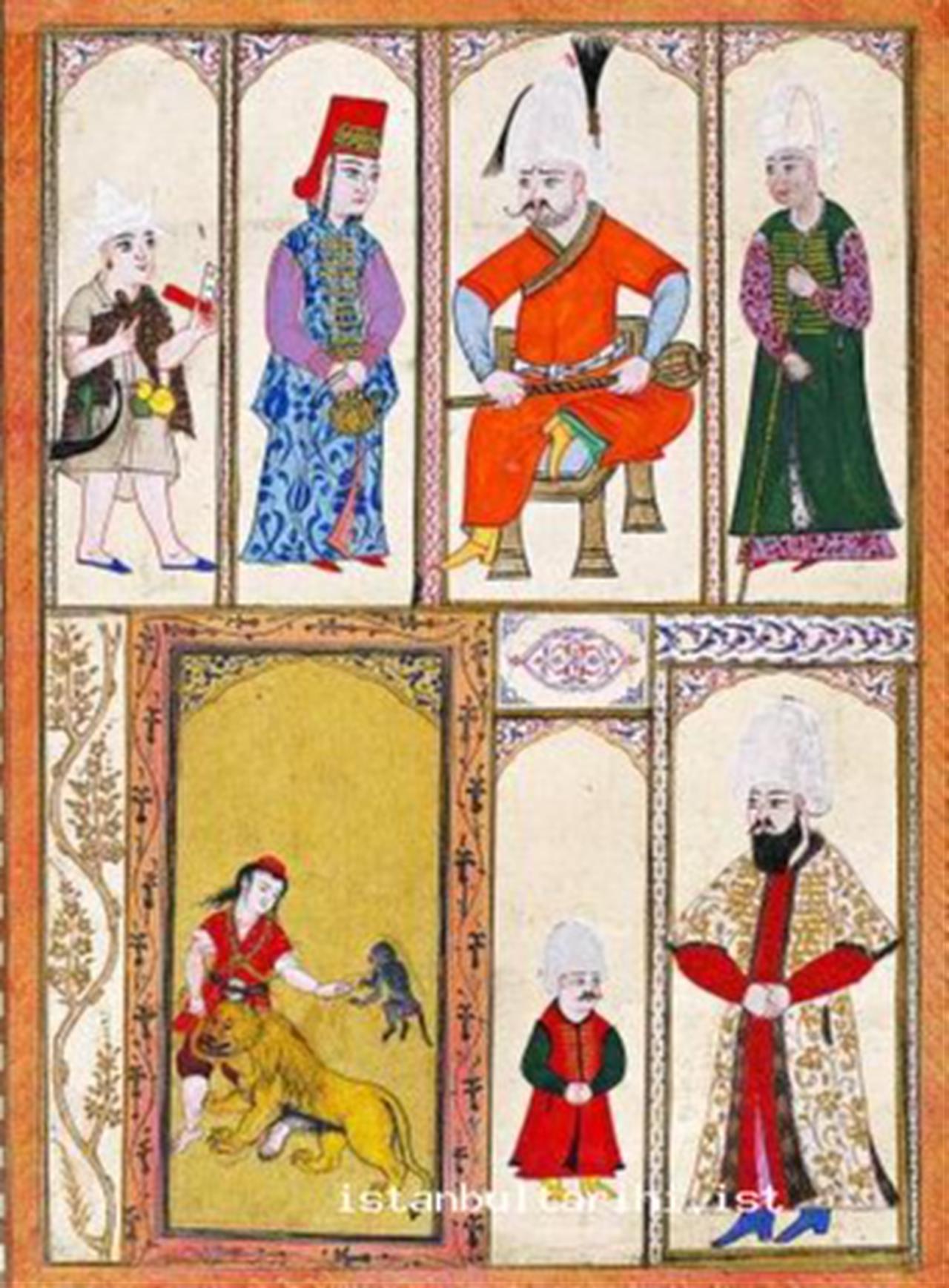

The Ottoman court was not a single room. It was an elaborate ecosystem. At its center stood the sultan, surrounded by grand viziers, bureaucrats, military elites, religious officials, palace servants, and members of the imperial household.

Foreign envoys visited often, carefully choreographed into ceremonies meant to impress and subtly intimidate.

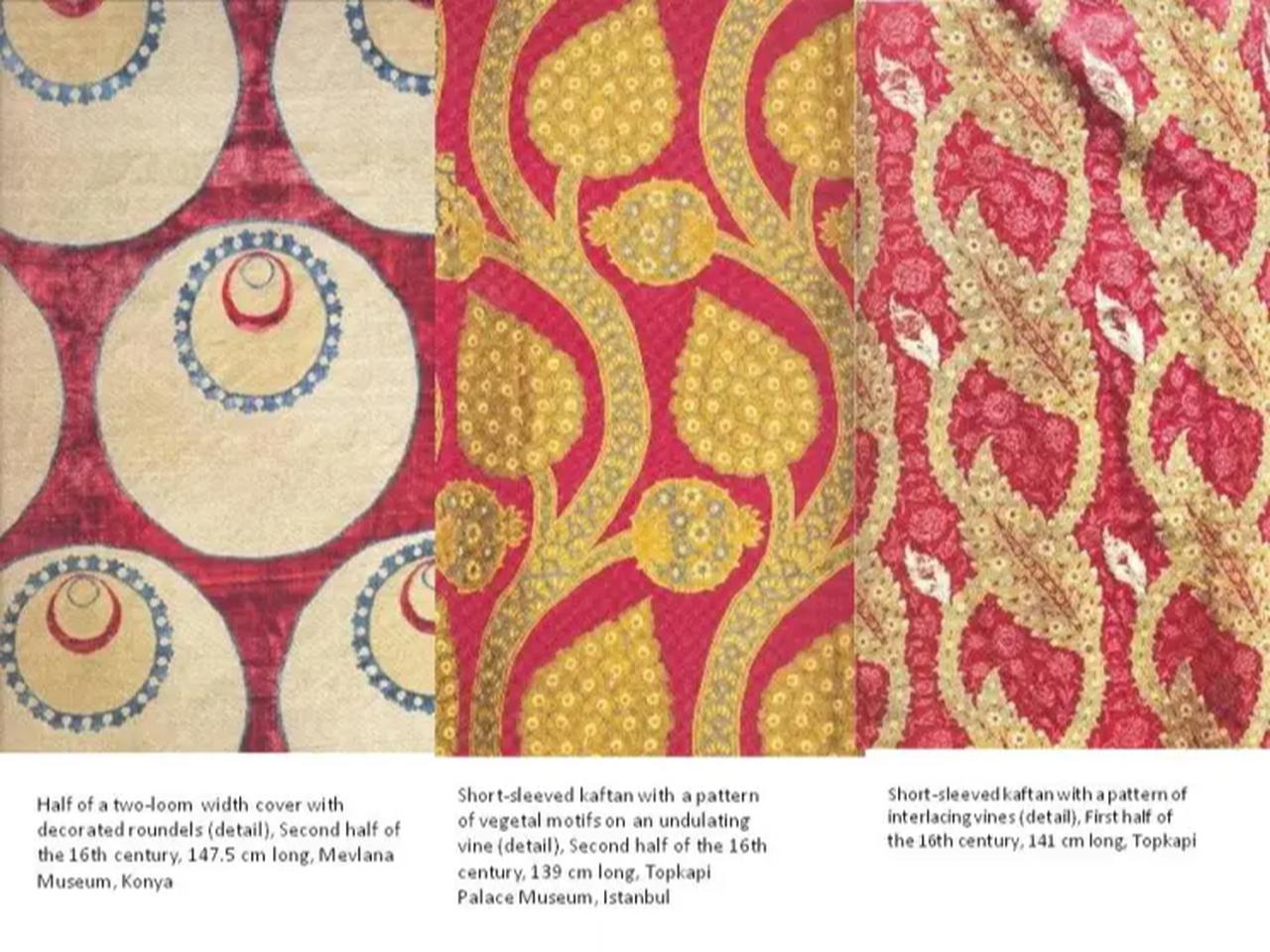

Every court appearance was a performance. Clothing set the stage. Rank could be read in fabric, cut, lining, and color. A kaftan was more than a robe; it was a coded message. Fur linings signaled privilege. Gold-threaded silks suggested imperial favor. Certain patterns and textiles were reserved for the highest authority.

In this court, hierarchy was not whispered, it was worn.

Few garments capture this world better than the imperial kaftan.

The exhibition style and status; imperial costumes from the Ottomans traced how robes preserved in the Topkapi Palace Museum functioned as clothing and political currency. These were luxurious objects, but also instruments of governance.

A key practice was the distribution of robes of honor, or hil’at. Awarded by the sultan or his representatives, these garments marked promotions, military victories, diplomatic milestones, and religious holidays.

Receiving a kaftan was not a gift in the modern sense. It was a public signal of favor, loyalty, and rank.

Foreign diplomats quickly learned the code. The number of robes, the quality of silk, and the presence of fur linings indicated the level of honor.

Some of the most prestigious kaftans were made from seraser, gold cloth or Italian velvet. The wearer became a walking emblem of Ottoman wealth and reach.

In this system, fabric was currency. Clothing was a visible extension of the state.

Court attendance reflected the empire’s social structure.

High officials and military leaders wore garments that emphasized discipline and authority. Religious figures wore wool rather than silk, signaling modesty and adherence to religious principles. Palace officials followed strict dress codes to maintain hierarchy.

Women of the imperial household, especially in the harem, also shaped court fashion. Their influence was indirect, but real. Through patronage, gifts, and ceremonial appearances, they guided textile production and luxury consumption. Their clothing, though less visible, was part of the same symbolic system.

Behind the splendor of court dress was an empire-wide textile network, Seher Selin Ozmen says.

Silk production, velvet weaving, embroidery workshops, and dyeing centers formed an economic and artistic backbone.

Ottoman silks were prized at home and across Europe, where they appeared in churches and aristocratic wardrobes.

Bikem Ibrahimoglu says that the kaftan itself was deliberately simple in cut, allowing the empire’s most valuable resource which is silk to carry political meaning through fabric, pattern, and layering.

This was no accident. Textile production was strategically supported, regulated, and incorporated into statecraft. The court didn’t just consume luxury but also organized it.

Fashion was not a byproduct of power; it was part of its infrastructure.

Selin Ipek notes that by the 19th century, court fashion had undergone a striking transformation.

The Tanzimat reforms introduced European-style uniforms. The goal was to modernize and align with Western powers.

Frock coats, waistcoats, trousers, and ties replaced traditional robes for many officials. This was more than a style change. It was a visual declaration of reform.

The bureaucrat’s body became a billboard for modernization.

Sultan Mahmud II and his successors understood clothing’s symbolic weight. Western dress signaled rational governance, international legitimacy, and a break from older military-religious structures.

Fashion was once again a tool to reshape political identity.

Ottoman architecture worked like court fashion. Scholars note how Mimar Sinan’s mosques and court complexes projected harmony, order, and imperial authority. Domes, symmetry, and light communicated power.

Court dress did the same on a human scale.

Architecture shaped how subjects experienced the empire. Clothing shaped how they embodied it.

Ottoman court fashion captivates today because of its clarity of purpose.

These garments were not about self-expression. They were about recognition, control, and communication.

In an era where fashion is again political from diplomatic dressing to luxury signaling, the Ottoman court feels modern. It reminds us: What we wear is always more than personal. It is political.

The Ottomans knew power must be seen to be believed. So they dressed it in silk, fur, and gold and sent it walking through marble halls.