Walking through Istanbul today, one can still find traces of a vast network of Ottoman hospitals and palace clinics, where the poor, mentally ill, and travelers were once welcomed for care.

Visitors may notice fragments of baths, marble entrances, and domed courtyards, but these remnants hint at centuries of medical innovation, urban planning and social welfare.

Scholars explain that the design of these spaces was deliberate, merging practical treatment with ritual, charity and psychological care.

Darussifas, or healing houses, were more than medical facilities; they were social institutions rooted in moral and charitable principles. In her study, Istanbul Darussifas (Hospitals) in the Classical Period, Nuran Yildirim shows that these hospitals emerged during the Abbasid period and became prominent under the Seljuks and Ottomans, with the first in Bursa in 1400 under Sultan Yildirim Beyazit.

Similarly, Abdullah Kilic, in his study Sifahane: Ottoman Healing Hospitals, emphasizes that they were funded by sultans, sultanas and elites, not only to support public welfare but to leave lasting legacies.

Architecturally, Darussifas had a rectangular shape, with domed patient rooms opening onto cloistered courtyards.

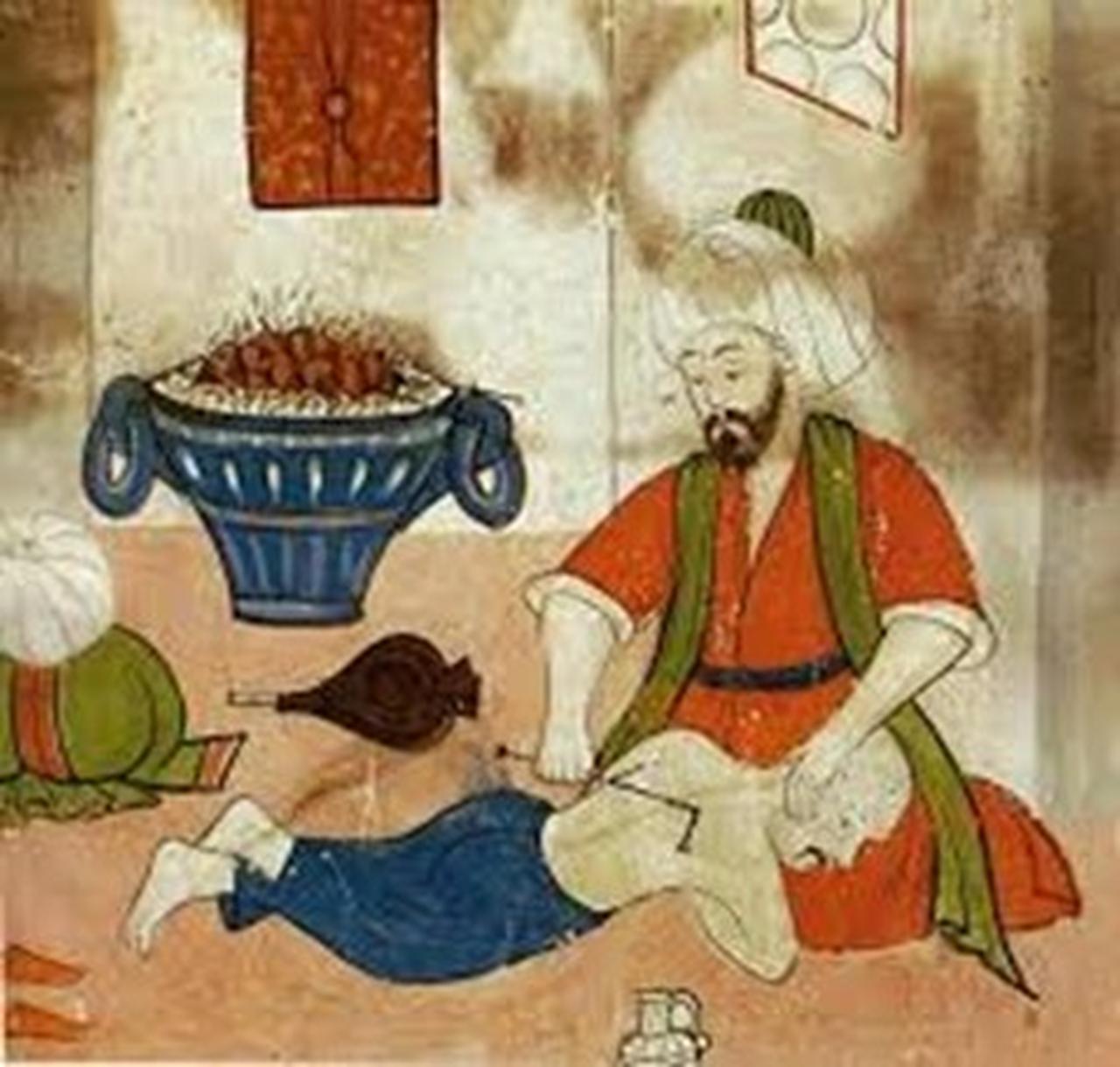

Central pools and attached baths highlighted the Ottoman belief in the connection between cleanliness and health. Seyma Afacan highlights in her study From Traditionalism to Modernism: Mental Health in the Ottoman Empire that staff duties were detailed in foundation deeds, emphasizing moral qualities, medical skills, mastery in syrups and pastes, and compassionate care.

Patients ranged from the destitute and travelers to those with mental illness, who could not be treated at home. Wealthy patients typically received private care, underscoring the charitable dimension of Ottoman medicine.

As Sherry Sayed Gadelrab observes in her book Ottoman Medicine: Healing and Medical Institutions, 1500-1700, hospitals were integrated into larger complexes, including mosques, schools, soup kitchens, baths, and markets, reflecting a broader social responsibility.

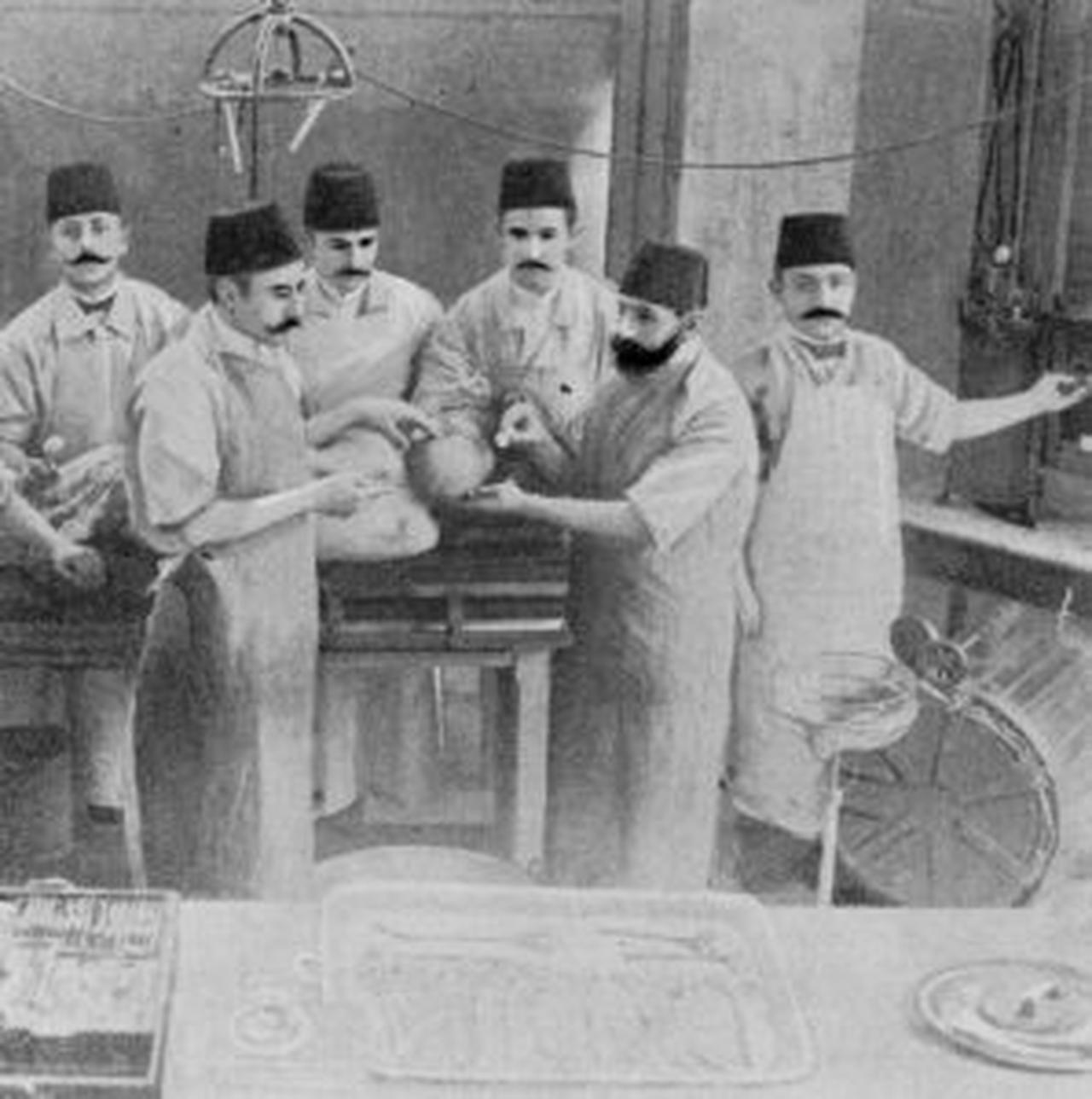

After Constantinople’s conquest, Sultan Mehmed II commissioned the Fatih Mosque complex, which included the Fatih Darussifa, opening in 1470. Physicians were required to be skilled in anatomy, humoral theory, and surgery regardless of religion or nationality.

The hospital provided free medication, meals, and burial services, while also training young physicians through mentorship and practical experience. Though damaged by repeated earthquakes, it remains a historically significant example of hospitals that combined education, charity, and urban planning.

The Haseki Hurrem Sultan Darussifa, completed in 1550, served all patients and employed physicians, surgeons, and pharmacists with defined moral and professional duties.

Treatments included individualized syrups and pastes, and a specialized section cared for mentally ill patients. By the 19th century, it had adapted to serve women before merging into municipal care.

The Suleymaniye Darussifa, opened in 1556, was the most prestigious. With extensive courtyards, central pools, and separate wings for psychiatric patients, it applied music therapy to mental health care.

Its affiliated medical school allowed apprentices to learn directly from experienced physicians while participating in patient care. Eventually, psychiatric patients were concentrated here, establishing it as the official bimarhane of the Ottoman state.

Completed in 1621, the Sultan Ahmed Darussifa exemplified the height of Ottoman hospital design and care philosophy. Historical records describe physicians selected for intelligence, mastery of medicine and pharmacy, kindness, and impartiality. The hospital featured domed patient rooms surrounding a central courtyard and pool, a bath emphasizing hygiene, and a small prayer area.

All patients were welcomed, with the Kizlar Agha supervising their welfare daily. Over time, it became dedicated to psychiatric care and later transformed into an industrial school, leaving only the bath, columns and entrance. Herbs like mint, sage, chamomile, and licorice were used extensively for treatment and prevention.

Inside Topkapi Palace, medicine was meticulously organized. The Hekim Basi, the chief physician, oversaw the Sultan’s health and the palace medical system. From the Enderun Hospital to the Terkiphane, where fragrant pastes, syrups, and theriacs were prepared, care blended science, ritual, and observation.

Physicians monitored patients, performed surgeries, and prescribed herbal remedies and prayers, combining practical medicine with spiritual guidance, as explained in Ottoman Palace Medicine: The Hekimbasi’s Secrets of Healing.

Among palace practices, macuns, thick herbal pastes made from dozens of spices, plants, and minerals, stood out. These were believed to strengthen the body, stabilize moods, and provide energy. Herbs such as mint, sage, chamomile, and licorice from palace gardens were central to preventive care. Treatments also incorporated sound therapy, gentle conversation, prayer and running water, creating a calm and restorative environment.

Ottoman care was deeply sensory and spiritual. Patients with mental health concerns were placed near fountains so flowing water could soothe agitation. Courtyards trapped breezes, softened light, and provided spaces for restless minds to settle. Scholars note that architecture, environment, and ritual were considered as essential to healing as medicine itself.

Though Darussifas and palace medicine no longer operate, their influence is evident in modern healthcare, urban planning, and social welfare practices. Ottoman hospitals demonstrate a model where medicine was inseparable from social responsibility, charity, education, and moral conduct. Understanding these institutions illuminates broader cultural values, showing a society where healing was not only a profession but also a communal duty.