History has a way of whispering its secrets—if you listen closely…

Night settled over the Kosovo plain. Beyond the ring of watch fires and fluttering banners, the land lay still beneath a vault of stars, its silence broken only by the restless snorts of horses and the footsteps of sentries on patrol. Within the Ottoman camp, on the eve of what would become one of the most consequential battles in Ottoman history, the army slept—dreaming of victory, of martyrdom.

At the heart of the encampment, in a tent pitched upon the open field, Sultan Murad I did not sleep. Instead, he spent the night in devotion. Raising his hands in supplication, he offered a prayer.

“Oh Allah! Sacrifice me for the sake of Islam; so long as my army is not defeated and destroyed at the hands of the enemy!”

It was not the prayer of a conqueror intoxicated by power, but of a ruler who believed that sovereignty carried obligation and that victory, if granted, must come at a price he himself was willing to pay.

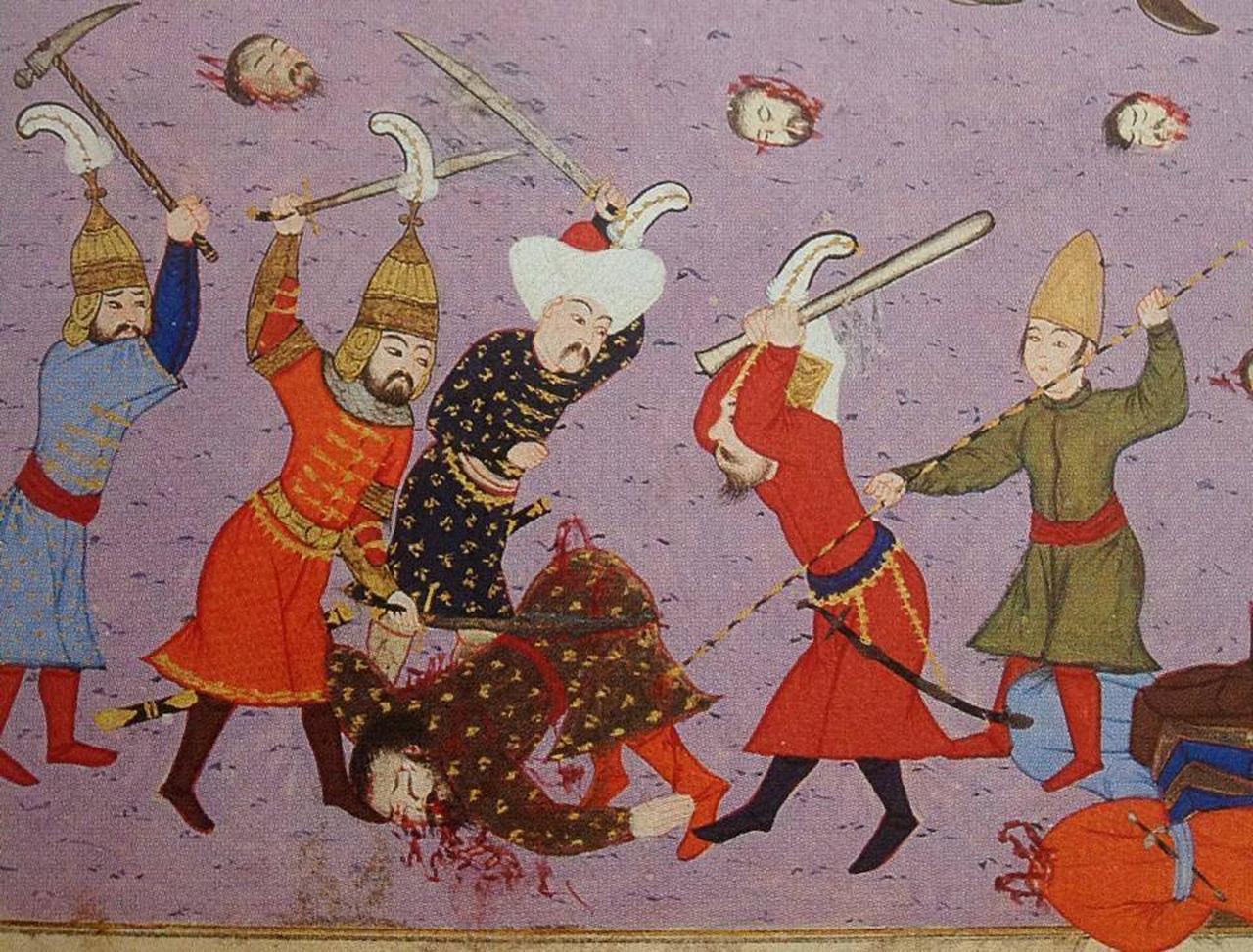

By sunset, the Kosovo plain would be soaked in blood. The battle would be won, the Balkan coalition broken, and Ottoman sovereignty in Rumelia secured. But the Ottoman Sultan who prayed for martyrdom would be dead.

He would be remembered as Hudavendigar Murad.

Hudavendigar is derived from the Persian “khudawandgar,” a word that carried profound meaning in the language of the medieval Islamic world. It is formed from two elements—Huda”, meaning Allah, God; and “vendigar,” meaning possessor, master, or one who holds authority. Together, they create a title that does not merely denote power, but more specifically, power exercised under divine sanction.

It was reserved for rulers who embodied the ideal of kingship, who stood as Allah’s deputy on earth, entrusted with the protection of his people and the preservation of order. To be called hudavendigar was to be recognized as a ruler who governed not only by the sword, but by law, piety and moral authority.

As Murad expanded his territories into Rumelia, as Edirne was established as the new capital, and as Ottoman dominance in the Balkans was consolidated and Balkan rulers came under the sultan’s vassalage, Ottoman chroniclers increasingly used the epithet of hudavendigar to encompass both the extent of Murad’s power and the manner in which it was exercised.

A manner that would find its final expression on the field of Kosovo.

The precise circumstances of Sultan Murad I’s death have long been debated. What is beyond dispute, however, is that on June 15, 1389, Murad became the only Ottoman sultan to lose his life on the battlefield, and that his death occurred on the very day Ottoman victory in the Balkans was confirmed.

According to one tradition, following the battle Sultan Murad rode onto the field of Kosovo to survey the fallen. As he moved among the dead and wounded, some sources say offering water to those in need, a Christian knight rose from among the corpses and fatally stabbed him.

A second account states that the assassination happened inside the Ottoman camp. In this version, a defeated knight requested an audience with the sultan. Murad consented, and as he received him, the man pulled out a concealed dagger and killed him, in an act that violated the codes of honor and chivalry by which warfare was followed in the 14th century.

In both versions, the assassin is most commonly identified as Milos Obilic, a Serbian noble who would enter Serbian folklore as a heroic figure. Ottoman chroniclers, meanwhile, ensured the legend of Sultan Murad would endure. He had prayed to die as a martyr if victory was granted. They recorded his end as divine acceptance of a righteous ruler’s plea.

And so the epithet hardened. Murad was no longer simply Hudavendigar by virtue of his life, but by the manner of his death.

The legend of Hudavendigar Murad is most keenly felt in two places.

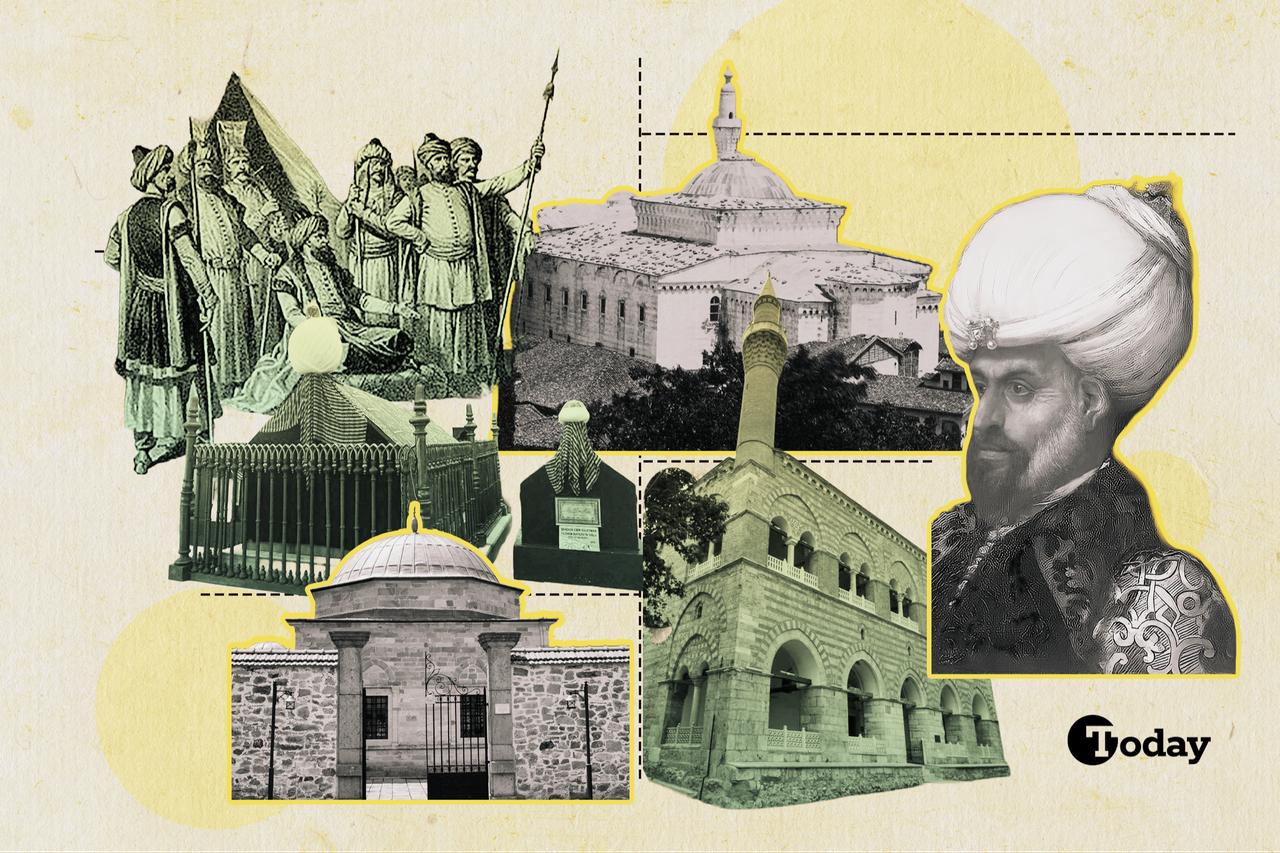

On the field of Kosovo, where Murad’s life ended and his prayer was answered, a modest turbe marks the site where his internal organs were buried— sanctifying the ground on which Ottoman sovereignty in the Balkans was won, a presence that would last for centuries. The plain is quiet now, open to the sky, surrounded by lush, verdant fields. Within the grounds of the tomb, a building erected during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II to accommodate pilgrims to the site has been converted into a small museum. It tells the story of the Battle of Kosovo and contains artifacts dating to the period of Sultan Murad I, inviting visitors to pause and reflect.

Far away, on another continent, Murad’s body rests in a tomb within the Hudavendigar Mosque complex, which he built in Bursa—the city conquered by his father, Orhan Gazi. This early example of Ottoman architecture also includes a medrese, a soup kitchen, a public bath, and a dervish lodge. It stands as a monument to a form of sovereignty that demanded accountability before Allah. As the soft light filters through its arched windows, one senses the early Ottoman vision of a state rooted in faith, benevolence, tempered ambition, and sacrifice. Here, as the call to prayer embraces you, the meaning of hudavendigar becomes clear, a reminder of what a ruler should be.

Some epithets are exaggerations. Some are aspirations. But every now and then, as with Sultan Murad I, they become the truest way history can honour a life.

In this series, I invite you to join me in discovering other Ottoman sultans through the epithets history chose to remember them by.

Until we meet again in the next “Sultan’s Salon”…