History has a way of whispering its secrets—if you listen closely…

The Ottomans rode through Anatolia, the Balkans, Mesopotamia, and the Holy Lands with a quiver of arrows at their waist and a bow curved like a crescent moon in their hands. These bows were more than weapons of war—they were symbols of power, the emblem of the Kayi tribe, of the Turkic warrior state… but, on rare occasions, they served a far darker, more chilling purpose. On Aug. 18, 1648, one such bow was unstrung, its silk cord removed and tightened around the neck of a sultan.

Discontent threatened the foundations of the empire. Taxes soared. Food was scarce. The ongoing war in Crete drained the Imperial Treasury. The Venetian blockade of the Dardanelles drove the hungry to riot in Istanbul. The janissaries were in a mutinous mood. The ulema shook their heads, weary of the sultan’s increasingly erratic behavior. Grand viziers and pashas jostled like chess pieces across the chequered board of power. In the harem, Kosem, the valide sultan, plotted and schemed to reclaim influence.

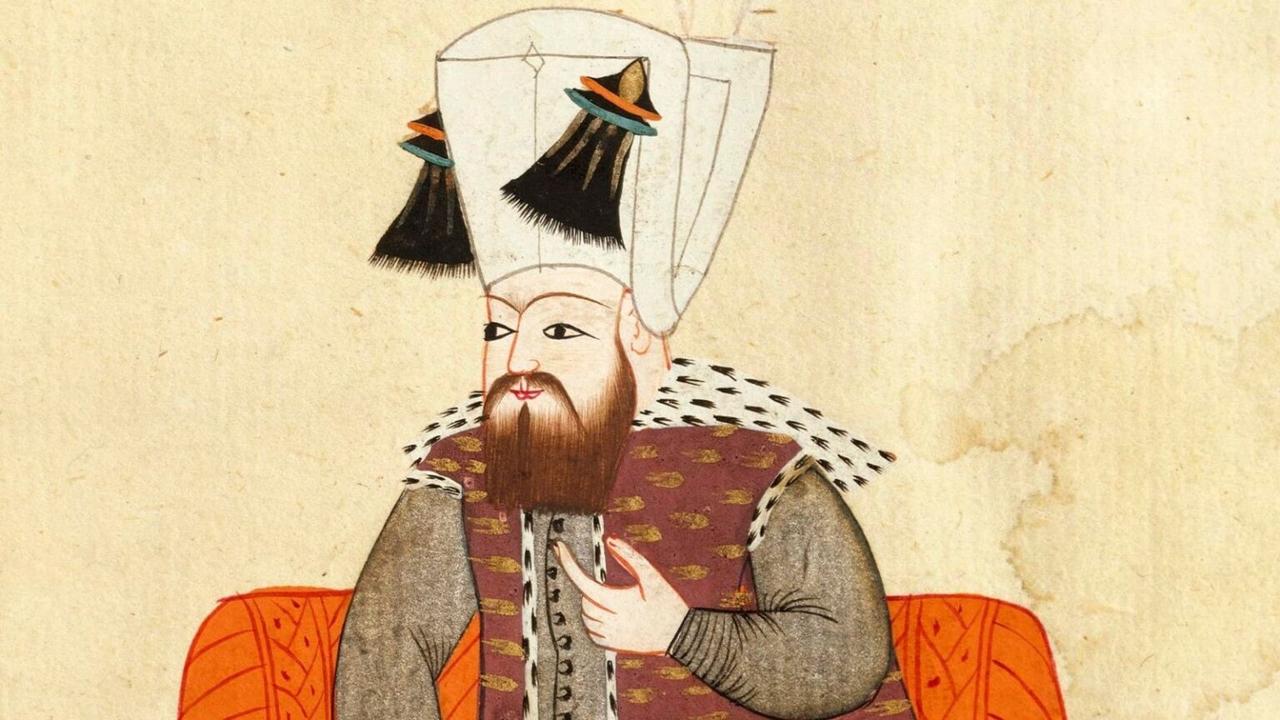

At the center of it all was Sultan Ibrahim I—a ruler whose eccentricities made him volatile, and whose life would soon hang by a silk thread.

History has branded him "Deli Ibrahim"–Mad Ibrahim. The tales are lurid: a fetish for sable and other furs, a harem of supposed excess, whims and fancies spun into legend. Yet such stories obscure a more nuanced portrait.

His elder half-brother, Sultan Osman II, had been deposed and killed by the janissaries–a story we will explore in the next "Sultan’s Salon." His brother and predecessor, Sultan Murad IV, had executed their other brothers, leaving Ibrahim in constant fear for his own life. Years confined in the kafes, the gilded cage of imperial princes, honed a mind shaped by isolation and terror, making him ill-prepared for the burdens of rule.

The caricature of the "mad sultan" painted by those who deposed and ultimately murdered him was intended to discredit him and justify their own treacherous actions. In truth, Sultan Ibrahim was generous towards the poor and did not neglect the affairs of state. He regularly attended the Divan, attempted to curb corruption, took an active interest in strengthening the navy, answered public petitions, and oversaw an impressive program of building and renovation, including the breathtaking tiled Sunnet Odasi, the Circumcision Room, and the gilded copper Iftar Kiosk in the Topkapi Palace.

Yes, he was flawed. Like us all. Yes, he could be unstable–not surprising after living in the kafes for years, the constant threat of death looming over him, or, as some scholars suggest, it was a brain tumor that affected his health and temperament. But far from the one-dimensional Deli Ibrahim, he emerges as a tragic figure, a ruler trapped in the brutal circumstances of his life and times, who would ultimately succumb to the executioner’s silken noose.

Sultan Ibrahim was deposed on Aug. 8, 1648, and declared mentally unfit to rule. He was succeeded by his 6-year-old son, Sultan Mehmed IV, and returned to the seclusion of the kafes.

Ten days after his deposition, betrayed even by his own mother acting as regent, the imperial guard dragged him from his chambers. A fatwa, a ruling under Islamic law, sanctioning his execution had been obtained from the Sheikh ul-Islam on the false charge of inciting insurrection.

On that late summer day, Ibrahim’s cries for mercy were ignored.

Several ornate 17th-century Ottoman bows survive and are on display in the Imperial Treasury at the Topkapi Palace. They are made of wood, horn, and sinew, lacquered and inlaid with mother-of-pearl or tortoise shell, adorned with gilt and sacred inscriptions. Some were used in battle, others for hunting, each bearing the scars of use–a small nick here or a faint scratch there. Now they hang in glass cabinets, their silk bow-strings long since vanished into dust.

Look closely at these handcrafted bows next time you visit the Topkapi Palace. Close your eyes. Imagine one being unstrung, its silk cord removed. Picture two palace bostancıs, the sultan’s own guards, holding either end of the silken thread, wrapping it tightly around Ibrahim’s throat, then drawing it taut in a single, decisive motion.

To spill imperial blood was forbidden. It was considered sacred, and shedding it would violate, desecrate, the House of Osman and undermine the divine authority of the dynasty. So the same silk bow-string used to propel arrows into flight became a weapon, ending the sultan’s life while preserving the sanctity of the imperial bloodline.

Press your ear to the glass, and you may hear how the bow whispers of power and betrayal, ritual and regicide, and how the Ottoman Dynasty was preserved through sacrifice.

Before you leave Topkapi Palace, step into the Circumcision Room, linger by the Iftar Kiosk, and admire every exquisite tile, every gilded curve. These stand as a testament to a man far more complex than history’s caricature. Perhaps you will view Sultan Ibrahim differently then.

Until we meet again in the next "Sultan’s Salon".