History has a way of whispering its secrets—if you listen closely …

On May 20, 1622, dusk descended over the Yedikule Fortress, cloaking its seven towers in a foreboding shroud of darkness. The last ember of sunlight slipped beneath the horizon across the Marmara Sea as the muezzin’s call to prayer drifted on the wind. Within the fortress walls, in a dank dungeon lit only by a flickering oil lamp, chains clinked faintly as a young man of 17, not yet old enough to grow a beard, knelt in silent prayer. Suddenly, the heavy iron door swung open, and he looked up.

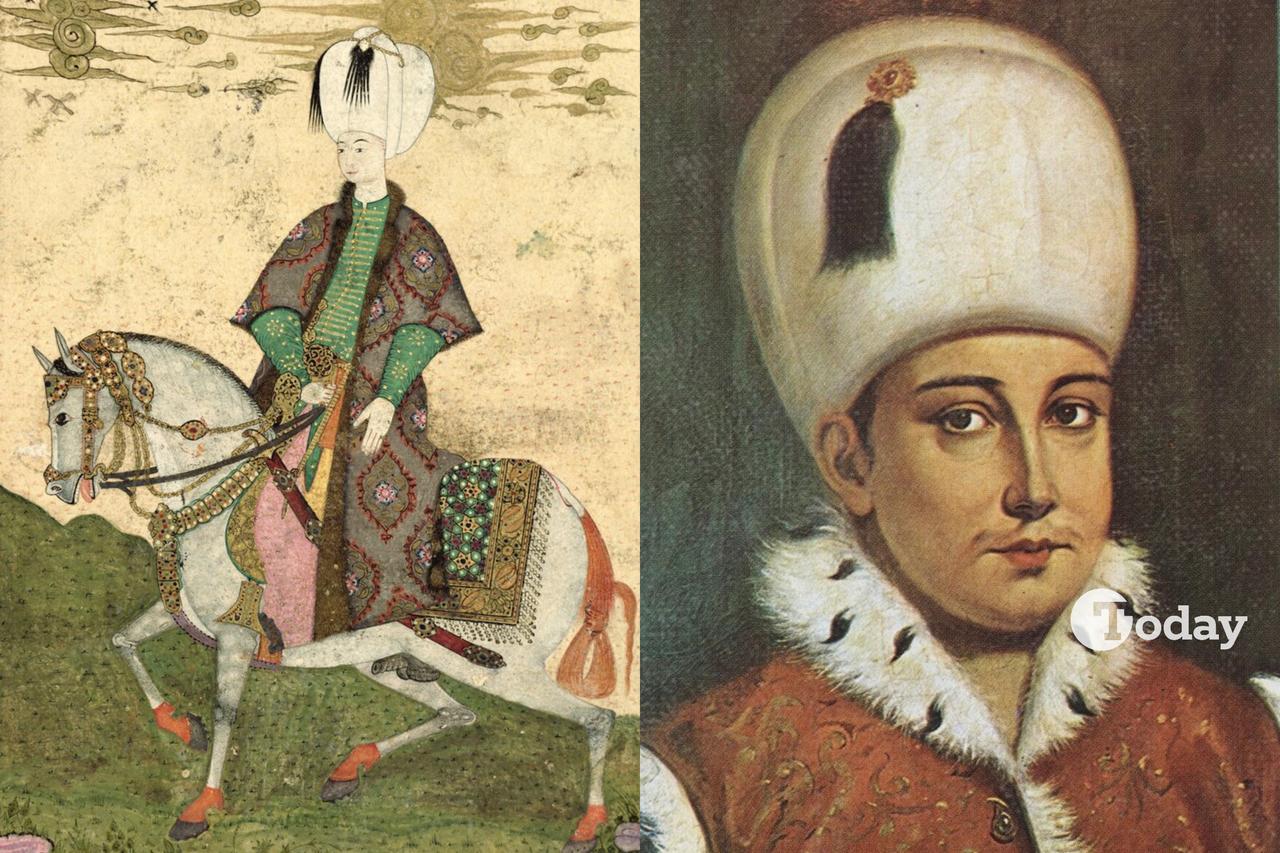

The young prisoner was Sultan Osman II, the elder half-brother of Sultan Ibrahim I, whose violent end we explored in the previous “Sultan’s Salon”.

Osman was a visionary—intelligent, ambitious, and idealistic, a young ruler determined to restore the Empire’s fading glory. Soon after ascending the throne, he led a campaign against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, eager to emulate the military triumphs of his ancestors. But his hopes were crushed. Poorly supplied and betrayed by disloyal troops, his army suffered humiliation at Khotyn. Osman returned to Istanbul defeated, yet his spirit remained unbroken.

With the piercing clarity of youth, he saw that corruption had seeped deep into the foundations of the Empire, shaking its very pillars. The bureaucracy had grown bloated and self-serving, while the Janissaries, the elite infantry corps, had become indolent and insubordinate. Once the scourge of Europe, they now lacked discipline on the battlefield and acted as a mutinous praetorian guard, meddling in state affairs.

Osman resolved upon radical reform. He would purge corruption, curb the power of the Janissaries, and raise a new army drawn from the loyal sons of Anatolia – an army that would answer to him alone.

It was a bold vision. And a fatal one.

The janissaries—yeniceri, literally meaning “new troops”—were once the pride of the Ottoman Empire. Founded in the 14th century by Sultan Murad I, they began as an elite corps drawn from the devsirme system, trained as soldiers, and forged into the most disciplined and feared fighting force of their age.

But power and privilege corrupt. By the 17th century, the janissaries had become the Empire’s greatest internal threat, their ranks filled with idlers and profiteers who defied authority and resisted reform.

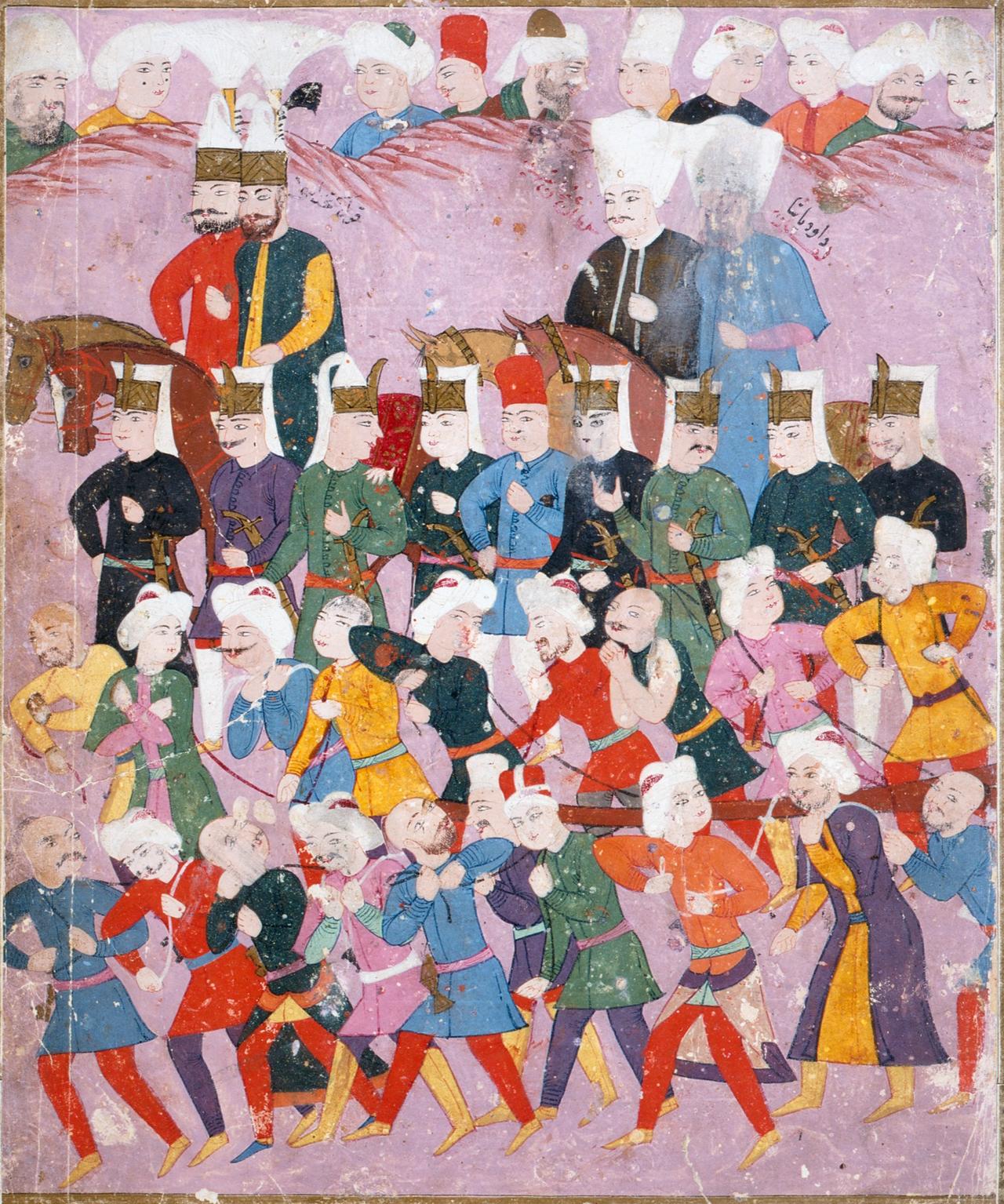

Rumours of Sultan Osman’s plans to disband the janissaries and strip them of their privileges spread through their barracks like flames fanned by the Lodos wind. Anger flared, and resentment ignited into open rebellion.

The mutinous janissaries gathered in the Atmeydani—the ancient Byzantine Hippodrome in Stamboul. From there, they stormed the gates of the Topkapi Palace, demanding the head of the grand vizier and the dismissal of the Sultan’s teacher and most trusted advisers.

Osman refused to yield to their demands. Believing he could calm the unrest, he appeared before them, trusting that his presence would command loyalty. But he was mistaken.

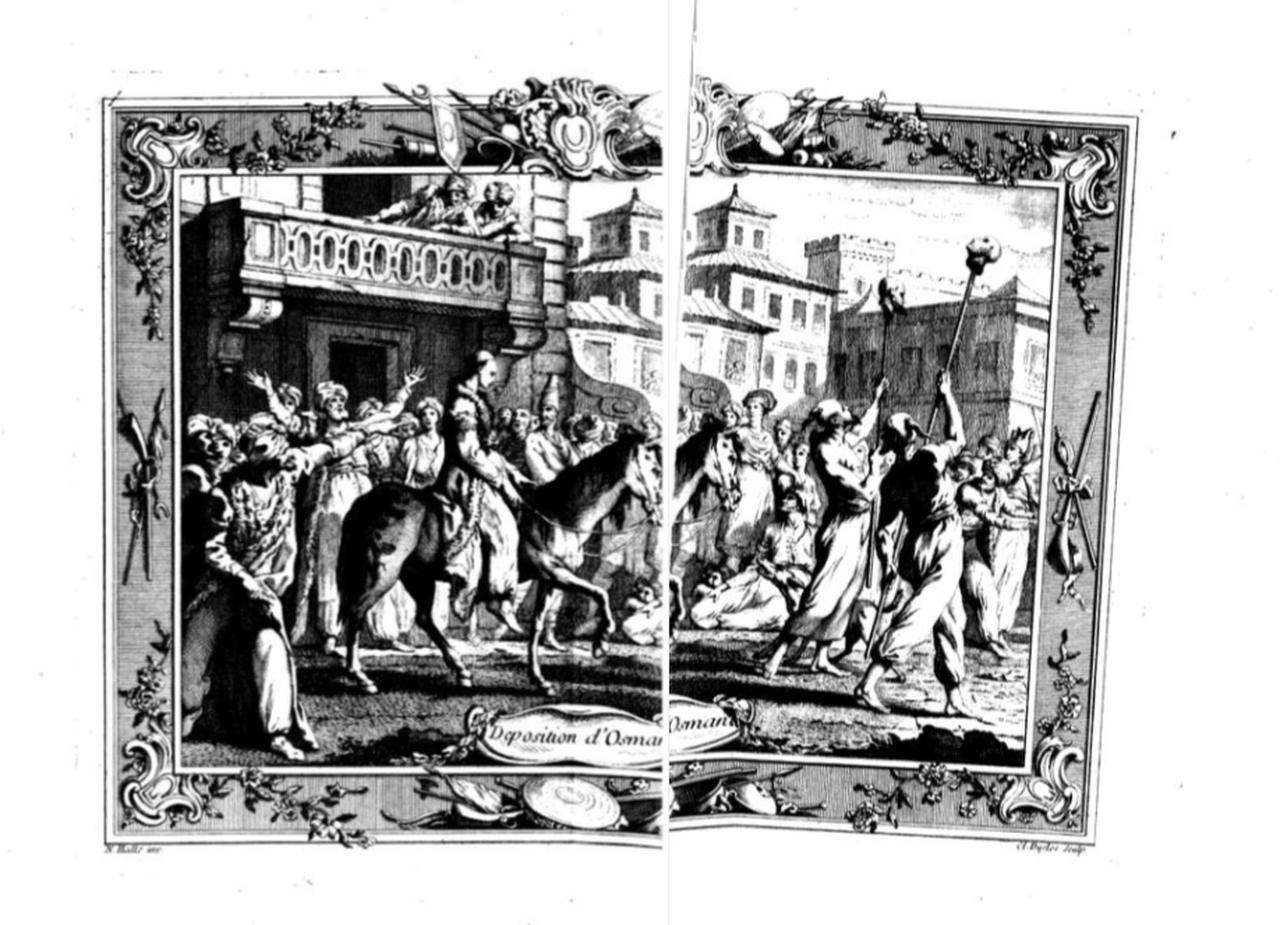

The rebels killed the grand vizier and the chief eunuch, and overthrew the young sultan. They dragged him from his throne, stripped him of his sword, knocked the turban from his head, and paraded him before the mob. On the orders of Kara Davud Pasha, Osman was taken to Yedikule, the Fortress of the Seven Towers, to await his fate.

Yedikule was built on the orders of Fatih Sultan Mehmed II (Mehmed the Conqueror) soon after the conquest of Constantinople. Rising behind the monumental Golden Gate of the Theodosian Land Walls, its solemn towers dominate the skyline above the Sea of Marmara like sentinels of stone. Although sources differ, Sultan Osman was likely taken to a cell on the second floor of the south tower of the Golden Gate, known as the South Marble Tower.

A deposed Sultan, especially one as impressive and idealistic as Osman, posed a serious risk to the rebels, so Kara Davud Pasha ordered his execution. As dusk fell on that fateful day, the heavy iron door to Osman’s dungeon swung open, and the Pasha entered, accompanied by 10 janissaries.

A violent struggle ensued. Osman fought for his life with such ferocity that the assassins struggled to overpower him. Eventually, the silk bowstring tightened around his throat, and the boy Sultan breathed his final breath within the cold stone walls of the Empire’s most infamous dungeon.

The murder of Sultan Osman II sent shock waves through the Empire. It was the first regicide in Ottoman history—and it was brutal. The young sultan was not only strangled but his body mutilated after death, his nose and ears reportedly severed and presented to the valide sultan as proof he no longer lived.

Vengeance, however, soon came. When Sultan Murad IV ascended the throne the following year, he ordered the execution of Kara Davud Pasha and the other ringleaders, and had their bodies displayed on the gates of Yedikule. For the next two centuries, the Empire would remain locked in a bitter struggle between reforming sultans and the reactionary Janissary Corps. This struggle only ended in 1826, with the Corps’ annihilation and dissolution in the Auspicious Incident.

Yedikule Fortress is currently undergoing a comprehensive restoration. Yet this important historical monument remains open to visitors, offering a fascinating glimpse into the past. Step beneath its vaulted gates, touch the rough limestone blocks, and gaze out over the Marmara where the sea meets the sky. Then listen to the Poyraz wind as it whistles through the South Marble Tower.

History still whispers there—of youthful defiance and the peril of dreaming too boldly.

And so concludes our exploration of the four acts of regicide in Ottoman history—the tragic fates of two brothers, Sultan Osman II and Sultan Ibrahim I, and of Sultan Selim III and Sultan Abdulaziz. Thank you for accompanying me through this chapter of our imperial past. I hope you leave with a keener curiosity and feel inspired to listen a little closer, as history whispers its secrets.

Until we meet again in the next “Sultan’s Salon.”