A new scientific study published in PLOS One has determined that the colossal eruption of the Thera volcano—known today as Santorini—occurred before the reign of Pharaoh Nebpehtire Ahmose, founder of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty.

This conclusion, drawn from precise radiocarbon dating of Egyptian museum artifacts, brings clarity to a long-standing debate that has divided archaeologists and Egyptologists for decades.

The research, conducted by Professor Hendrik J. Bruins of Ben-Gurion University and Professor Johannes van der Plicht of the University of Groningen, directly compared radiocarbon data from objects linked to Egypt’s late 17th and early 18th Dynasties with data from the volcanic deposits of Thera. This period marks the transition from Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period to the New Kingdom, when Ahmose unified Upper and Lower Egypt after defeating the Hyksos.

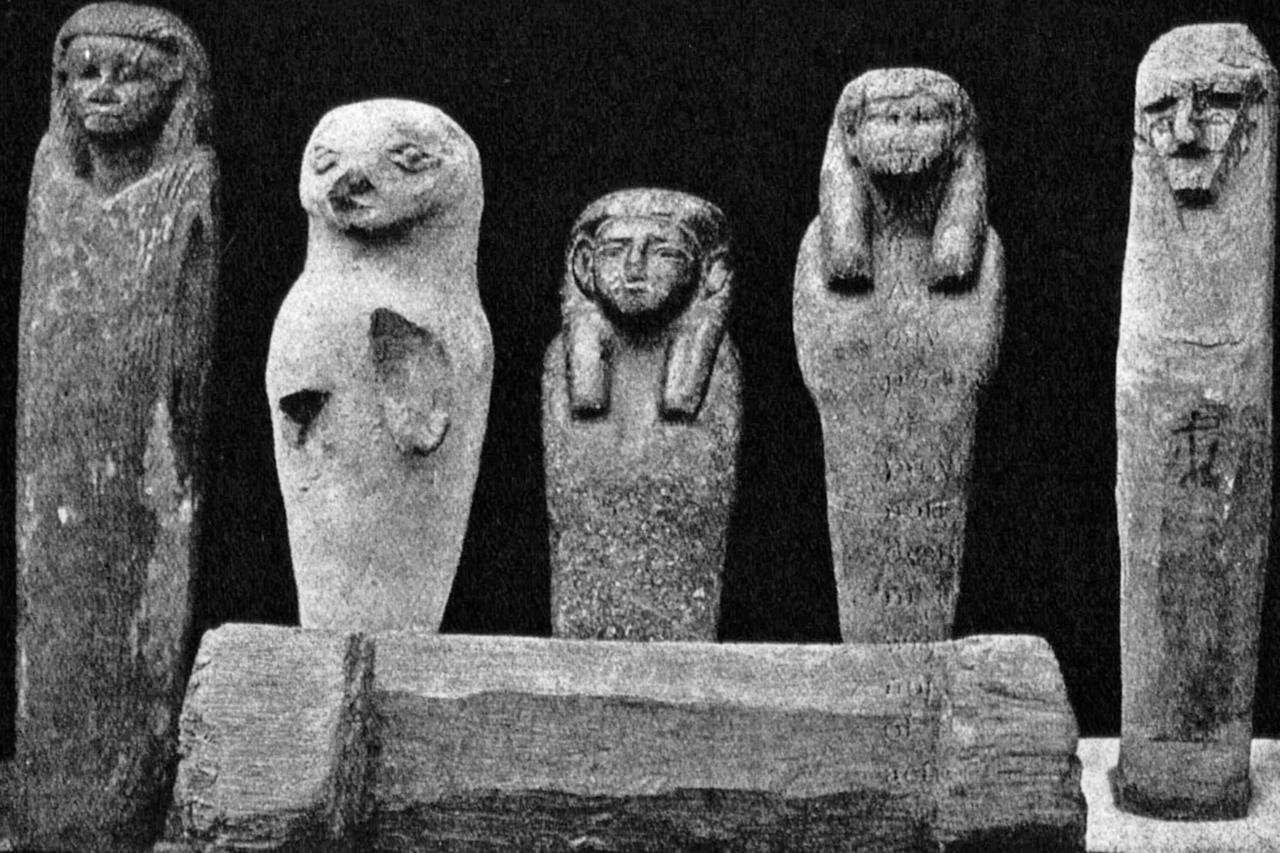

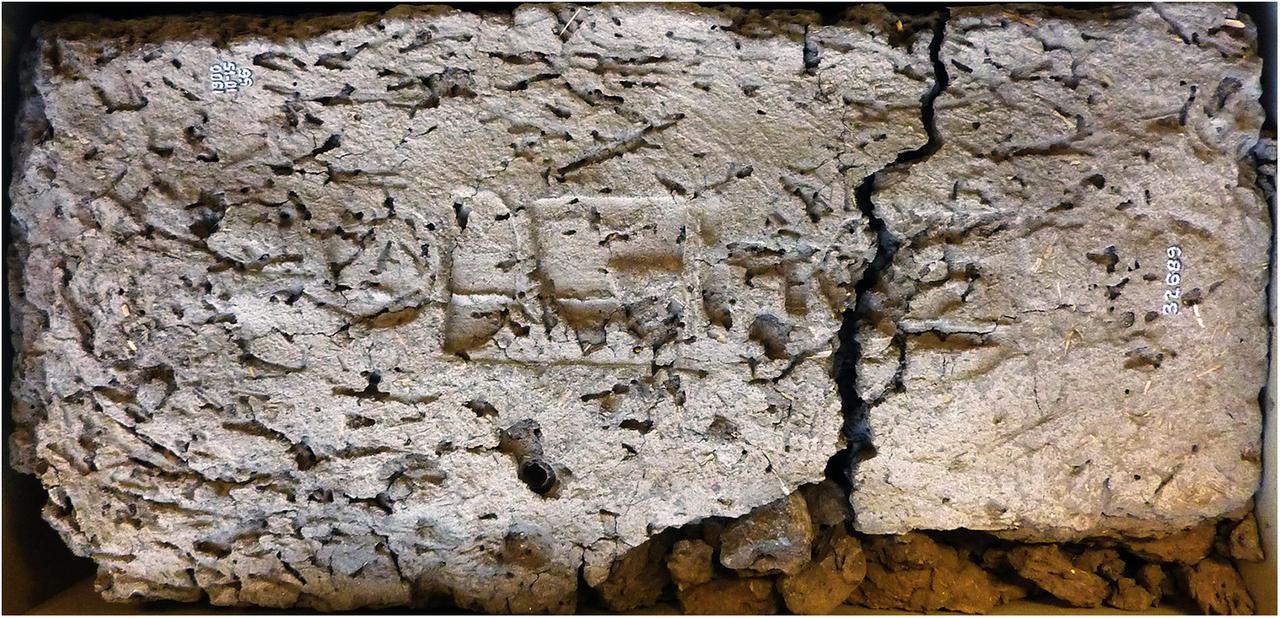

Among the Egyptian artifacts analyzed were a mudbrick stamped with Ahmose’s throne name “Nebpehtire” from the British Museum, a linen burial cloth of Queen Satdjehuty, and wooden shabti figurines from Thebes housed in the Petrie Museum. Using accelerator mass spectrometry and the IntCal20 calibration curve, the scientists measured the radioactive decay of carbon isotopes in organic materials such as straw and linen.

By comparing radiocarbon “time signatures” rather than relying solely on historical chronologies, the researchers found that the Thera eruption predates the rule of Ahmose. The findings contradict earlier hypotheses suggesting that the eruption coincided with his reign and may have inspired the “Tempest Stela,” an inscription describing destructive storms and darkness over Egypt.

Instead, the data confirm that the eruption took place several decades earlier—most likely during Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period—before the country’s reunification under Ahmose.

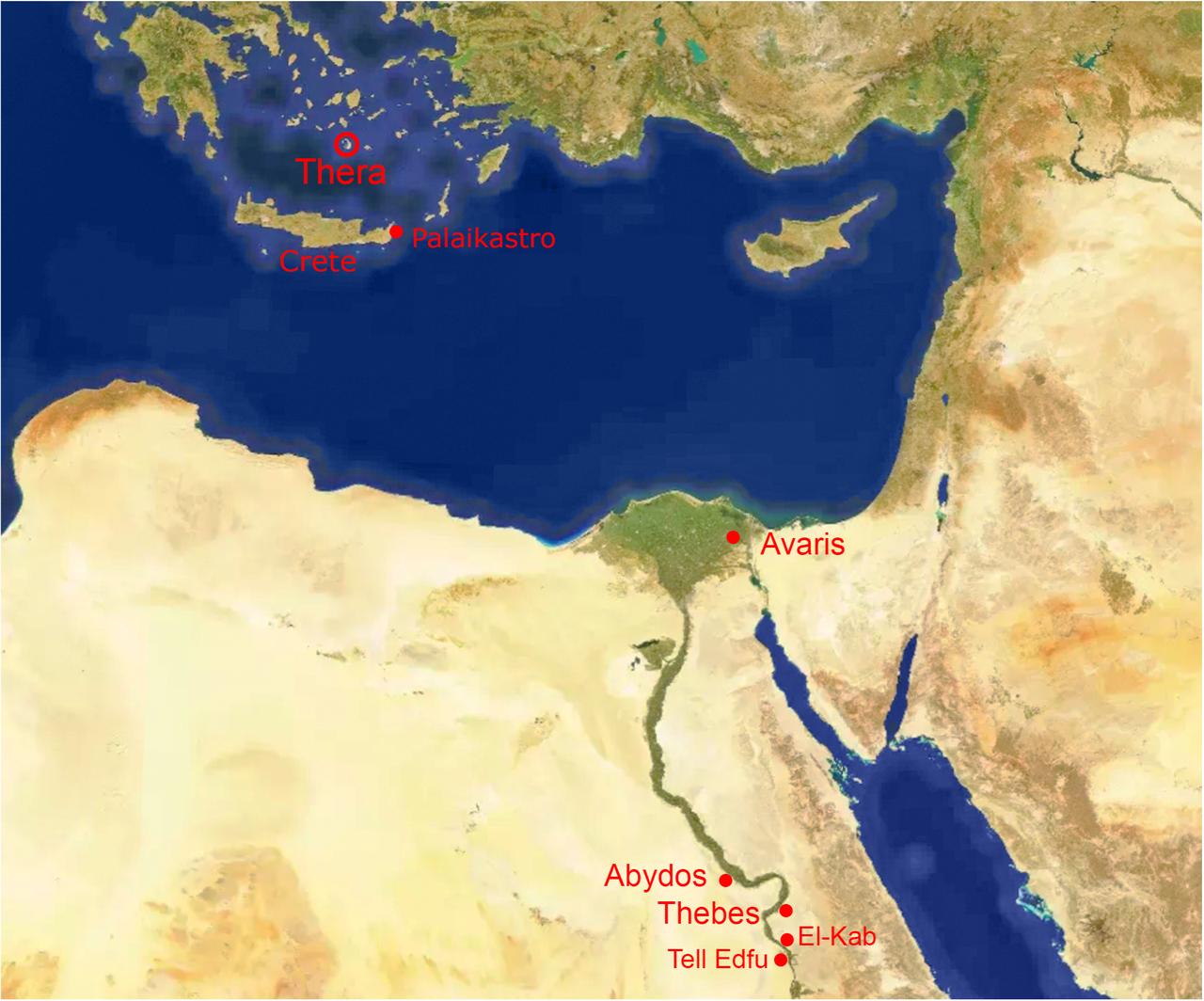

The Thera eruption, which buried the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri beneath thick volcanic ash, was one of the largest known eruptions in human history. Geologists estimate it expelled around 80 cubic kilometers of volcanic material, surpassing even the 1883 Krakatoa eruption in Indonesia. The event devastated coastal settlements across the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, sending ash and pumice as far as Crete, Rhodes, Türkiye, and possibly Egypt.

Archaeological evidence from coastal sites in Crete, Israel, and Türkiye indicates that the explosion triggered massive tsunamis, wiping out Minoan harbors and reshaping trade routes across the region.

The study supports what scholars call a “low chronology” for the start of the New Kingdom—placing Ahmose’s reign slightly later than some traditional estimates—and a “high chronology” for the Middle Kingdom. Together, these adjustments lengthen the Second Intermediate Period, suggesting a greater temporal gap between Egypt’s Middle and New Kingdoms than previously assumed.

The authors emphasized that radiocarbon dating, when applied to securely provenanced museum artifacts, can bridge the gap between archaeological and historical records. Their approach, comparing uncalibrated radiocarbon data from both Egyptian and Aegean contexts, provides what they described as “the first direct, scientific synchronization between these two great civilizations.”