In the coastal region of western Türkiye, near modern-day Izmir, archaeologists have uncovered an extraordinary set of ritual pits at the ancient site of Liman Tepe, shedding new light on Bronze Age ceremonial life.

The findings suggest that fire rituals, food offerings, and even animal sacrifices played a crucial role in the spiritual and social lives of communities around 2,000 B.C.

These pits, filled with charred seeds, animal bones, standing stones, and ceramic vessels, reveal the intricate symbolism and social importance of communal feasting and sacred practices in early Anatolian societies.

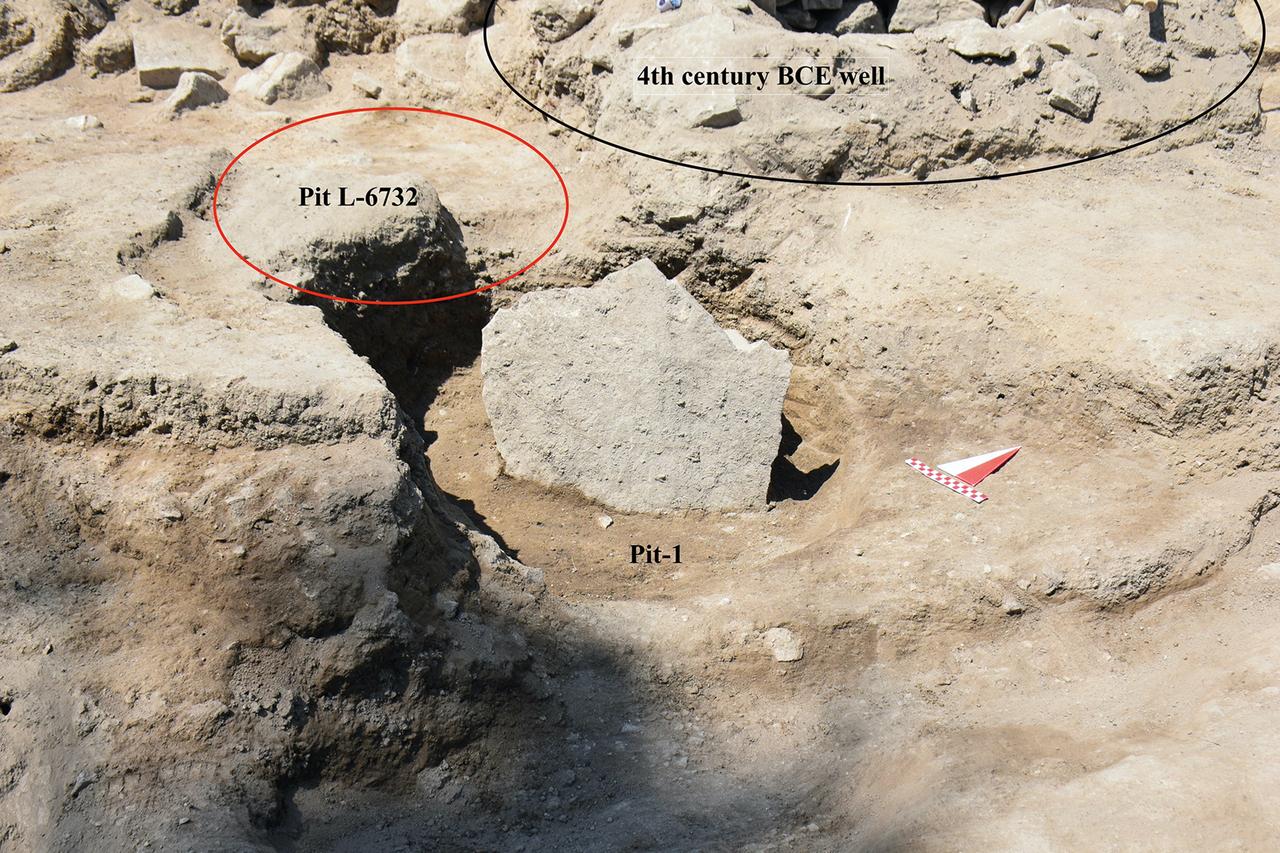

The excavation of four ritual pits in the settlement of Liman Tepe reveals a layered history of symbolic behavior.

One pit, dubbed Pit-1, featured a standing stone at its center surrounded by pottery, grape seeds, wheat, and animal remains—all signs of a possible food-based ritual or offering. Another, Pit-3, held an unfired clay altar with carefully placed vessels and broken bones of pigs, sheep, and cattle.

Significantly, Pit-4 contained the skeleton of a pig laid out with its head and body separated—a potential sacrificial rite. Two cups were found next to the animal's head, possibly once filled with blood.

“These arrangements were no accident,” said archaeologist Assistant Professor Umit Gundogan, who led the study. “They were performed with intention, reflecting beliefs, fears, and the social bonds of the community.”

Alongside the pits, researchers identified a large megaron structure—an oval building with a stone-paved floor and hearth, distinct from nearby domestic spaces.

This suggests that it may have served a sacred purpose, perhaps linked directly to the rituals occurring in the adjacent pits.

This architectural transformation highlights a growing emphasis on organized religious or ceremonial space during the Middle Bronze Age, reinforcing the connection between ritual and societal structure.

Analysis of the pits uncovered not just signs of sacrifice but evidence of communal feasting. Burnt grape seeds—possibly the remains of wine—paired with animal bones, indicate that food and drink were central to these rites.

The use of imported “Minoanizing” vessels suggests links with the Aegean world, possibly through trade or shared ritual practices.

Feasts likely served both spiritual and social functions—helping to reinforce community cohesion and, perhaps, respond to environmental crises like droughts.

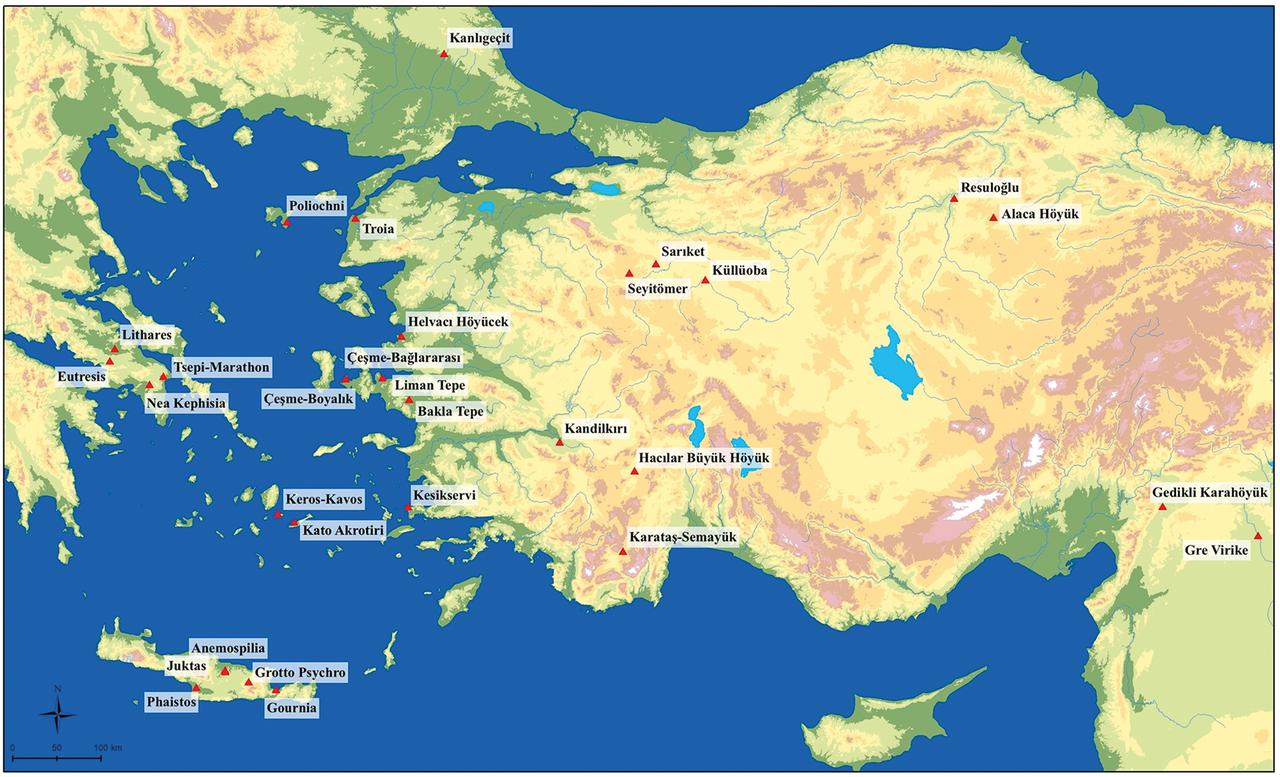

The region’s location between the Aegean and inland Anatolia positioned it as a cultural crossroads.

Archaeological parallels with both Crete and central Anatolia suggest that western Anatolia blended diverse ritual traditions, absorbing influences while maintaining unique local customs.

Unlike earlier periods, where scattered bones marked ritual activity, the second millennium B.C. shows the emergence of whole animal offerings and more complex ceremonial arrangements.

This evolution reflects changing ideologies and perhaps a response to increasing political instability and environmental stress.

By studying these humble cavities filled with ash, bone, and broken pottery, researchers are unlocking the ceremonial heart of Bronze Age life in Türkiye. As Gundogan notes, “Each pit is a microcosm of belief, survival, and identity—a sacred archive beneath the soil.”