King Antiochus II Theos took the stage of history through rebellion, and around 2,300 years ago, founded a city beside a fertile plain. The Seleucid king named this city after his famously beautiful wife, Queen Laodice. This city, which would later lie within the boundaries of what is now called Denizli, came to be known as Laodicea. From its earliest days, Laodicea became a prominent settlement. However, as time passed, this favored city also drew enemies — at one point, it was invaded by the Ptolemaic Kingdom. To save the city from occupation, King Antiochus had no choice but to make a peace agreement. But in those times, peace was often achieved through marriages!

To rescue the city, the king divorced Queen Laodice — for whom he had named the city — and married the daughter of the invading King Ptolemy II. Yet, soon after, King Antiochus II died suddenly. From then on, Laodice’s name became associated with intrigue and conspiracy. The city later came under the control of the Kingdom of Pergamon, and eventually became part of the Roman Empire. Throughout its history, Laodicea endured nine major earthquakes and was rebuilt each time. However, a devastating quake in the 7th century A.D. reduced it to rubble, and from the era of the Anatolian Beyliks onwards, it became nothing more than a pasture for shepherds.

Hidden within the fertile lands of Denizli is the ancient city of Laodicea, with its fascinating and dramatic past. Once a major hub of textiles and trade, Laodicea was among the most significant metropolises in Anatolia. It’s home to monumental structures and holds religious significance as well, being mentioned in the modern Bible and known as one of the Seven Churches of early Christianity.

Laodicea also boasts the largest hippodrome in Anatolia and is renowned for the monumental fountain dedicated to Emperor Trajan. The city was rediscovered by Western archaeologists during the late Ottoman period. However, during the construction of the railway station in the late 19th century, led by the British company ORC, countless sculpted stones and statues were unearthed.

At the time, the Ottoman Empire had just enacted the “Asar-i Atika Regulation” to protect cultural heritage. In response, authorities demanded the return of 1,160 historical artifacts discovered during the excavation. Nevertheless, it’s alleged that many of these items were smuggled illegally to England.

Systematic archaeological excavations at Laodicea have been ongoing since 2003 under the leadership of Professor Celal Simsek. Over the past 22 years, streets, a small theater, and various structures have been unearthed and restored. Yet only 1.3% of the city has been excavated so far. Many significant structures, including the massive hippodrome and the bath complex, still await discovery.

Türkiye İş Bankası has pledged support for the excavations at Laodicea and neighboring Tripolis for the next five years. Taking this opportunity, we paid a visit to the ancient city.

Amid the poppies blooming in spring, excavation leader Prof. Simsek shared insights with us: “This is not an ordinary place. In antiquity, Laodicea was a major metropolis, nearly as important as Ephesus. The city spanned eight square kilometers and had a population approaching 80,000. Textile production was just as important then as it is now. Laodicea has now become one of the most prominent shining ancient cities in Anatolia. Its significance in early Christianity also draws many foreign tourists.”

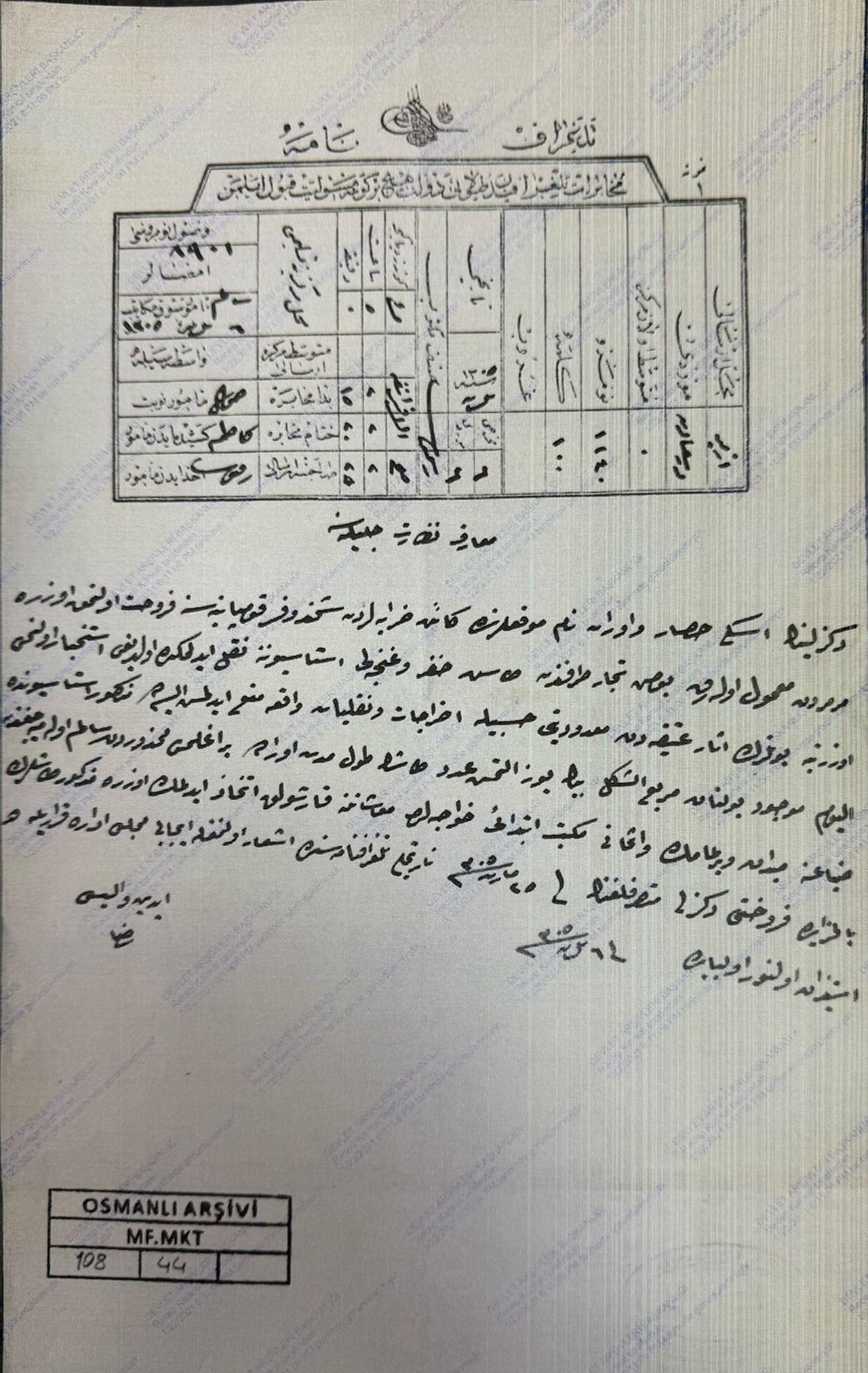

Prof. Simsek also emphasized their efforts not only to uncover Laodicea’s ancient structures but also to recover artifacts smuggled abroad. He noted that records of these thefts exist in Ottoman archival documents.

“We have an archive document dated 1889. During that time, 1,160 artifacts — believed to include reliefs and statues — were transported to the Goncalı train station. The Governorate of Aydın sent an official letter demanding the return of these historical artifacts, which could have filled an entire museum. Some pieces were collected in Denizli’s Gazi Primary School. However, we believe that many were smuggled abroad,” he explains.

“In fact, we have confirmed and published academically that two of our artifacts are in the British Museum, and two are at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Simsek adds. “We’re continuing our investigations. As the excavations proceed, we’re also tracking down the heads of statues we uncover. We’re writing reports and formally requesting the return of our cultural heritage. These artifacts belong to Anatolia.”

Prof. Simsek also proudly noted that Laodicea was the first site in Türkiye to host excavations throughout the year: “In my view, year-round excavations have contributed tremendously to the field of archaeology and to Anatolian archaeological heritage. This system now continues without interruption,” he says.

Professor Celal Simsek concludes with heartfelt words:

“Laodicea is my beloved. Over the years, I’ve learned many lessons here. The greatest one is this: What truly remains in this world are the services we render for humanity. We, ourselves, will eventually pass on — but those contributions endure.”