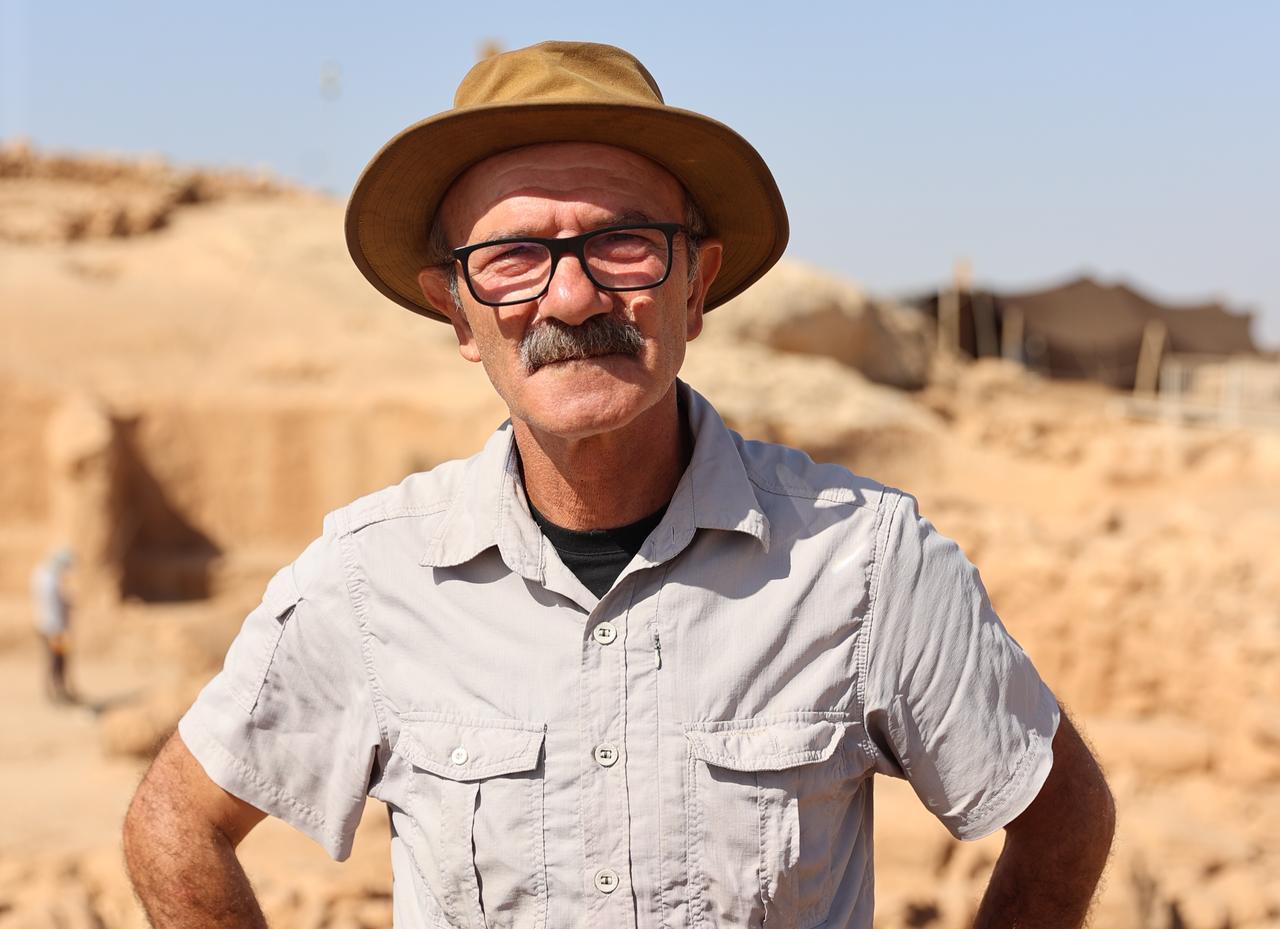

Archaeologists at Karahantepe in Sanliurfa are working to pin down what Neolithic communities ate by tracking microscopic plant residues preserved on house floors and grinding stones. The excavations, conducted under the Tas Tepeler (Stone Mounds) Project in Türkiye, are led by Professor Necmi Karul, who says the team is mapping where food was processed and stored inside buildings and how those spaces were used over time.

Karul notes that the team has identified in-house features such as storage areas and grinding benches.

Occupation surfaces have kept activity traces in place, yet many residues cannot be told apart with the naked eye. To reach those clues, the crew is dry-sieving soil layer by layer down to the floors and sorting the tiniest pieces that turn up.

The team then uses flotation—a standard technique that washes soil in water so light botanical remains rise and can be skimmed off—to separate fragile plant fragments.

“We float especially the plant remains and pick out very small pieces,” Karul explains, adding that chemical and micro-analyses reveal which parts of a room were used for which tasks and which plants people handled there. This approach, he says, lets researchers define spaces more clearly.

Grinding stones stand out as a key line of evidence for food preparation. According to Karul, a particular stone could show which plants were ground and may speak to the shift toward cultivation and domestication in Neolithic settlements.

“For this, the surface of the stone is washed with pure water, the collected water is separated, and the sediments are taken into containers. Then the sediments are settled and the upper water is evaporated to make them suitable for analysis,” he says.

Karul underlines that the end goal is to piece together as much as possible about prehistoric communities: who they were, what kind of biological makeup they had, how they interacted with their environment, and what they ate.

Pulling these data together, he notes, helps researchers understand both the individual and the wider society that built the walls and used the tools.

The plant findings retrieved from Karahantepe will be examined by specialists at Istanbul University, where detailed analyses are set to follow.