In a little-known episode of the Philippine-American War, the Ottoman Empire's Sultan Abdulhamid II played a pivotal role in preventing what could have escalated into a religious war in the Philippines, according to historical records from the early 1900s.

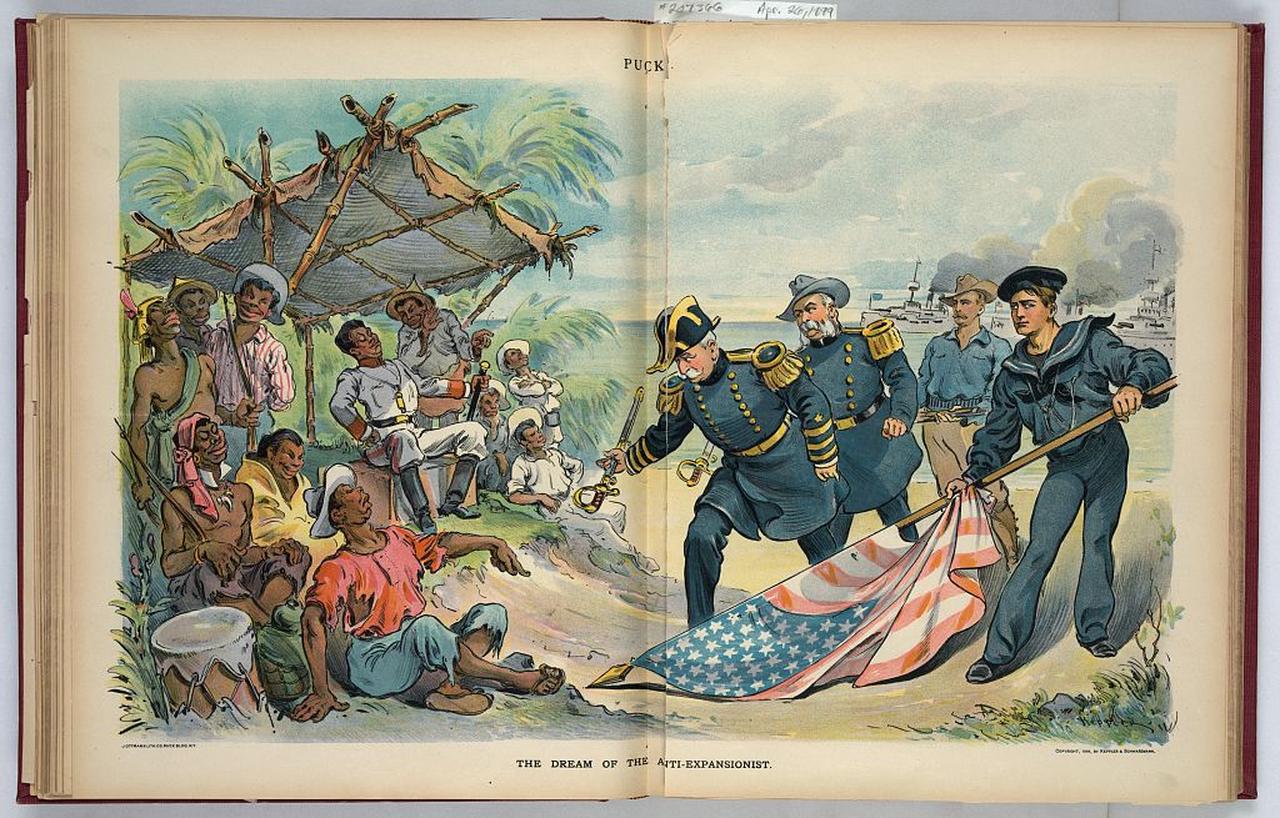

The diplomatic intervention came as the United States struggled to establish control over the newly acquired Philippine territories following the Spanish-American War, with American officials fearing that Muslim Moro populations would launch a holy war against U.S. forces.

The episode unfolded against the backdrop of the Philippine-American War, which began in 1899 following the U.S. acquisition of the Philippines from Spain through the Treaty of Paris. While the conflict with Filipino independence forces led by Emilio Aguinaldo dominated the northern regions, American authorities faced a separate challenge in the southern Philippines, where the Muslim Moro people, particularly in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago, posed the threat of religiously motivated resistance.

Secretary of State John Hay approached Oscar Straus, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, with an unprecedented request in 1899: convince the Ottoman Sultan to use his religious authority as caliph to discourage Filipino Muslims from joining the rebellion against American rule.

Straus, serving his second mission to the Ottoman Empire from 1898 to 1900, successfully negotiated with Sultan Abdulhamid II to intervene on behalf of American interests. Despite the Ottoman Empire's geographical distance from Southeast Asia and its own internal challenges as the declining "Sick Man of Europe," the sultan readily agreed to assist American forces. His approach was rather pragmatic, to avoid unnecessary hostilities between the West and Muslim populations worldwide, despite his "pan-Islamic" ideology that sought to unite Muslims globally.

The sultan's willingness to aid American forces demonstrated the complex calculations facing the Ottoman Empire during this period. Abdulhamid II, who reigned from 1876 to 1909, was simultaneously dealing with internal decline and external pressures while maintaining his role as the spiritual leader of the global Muslim community through the Caliphate.

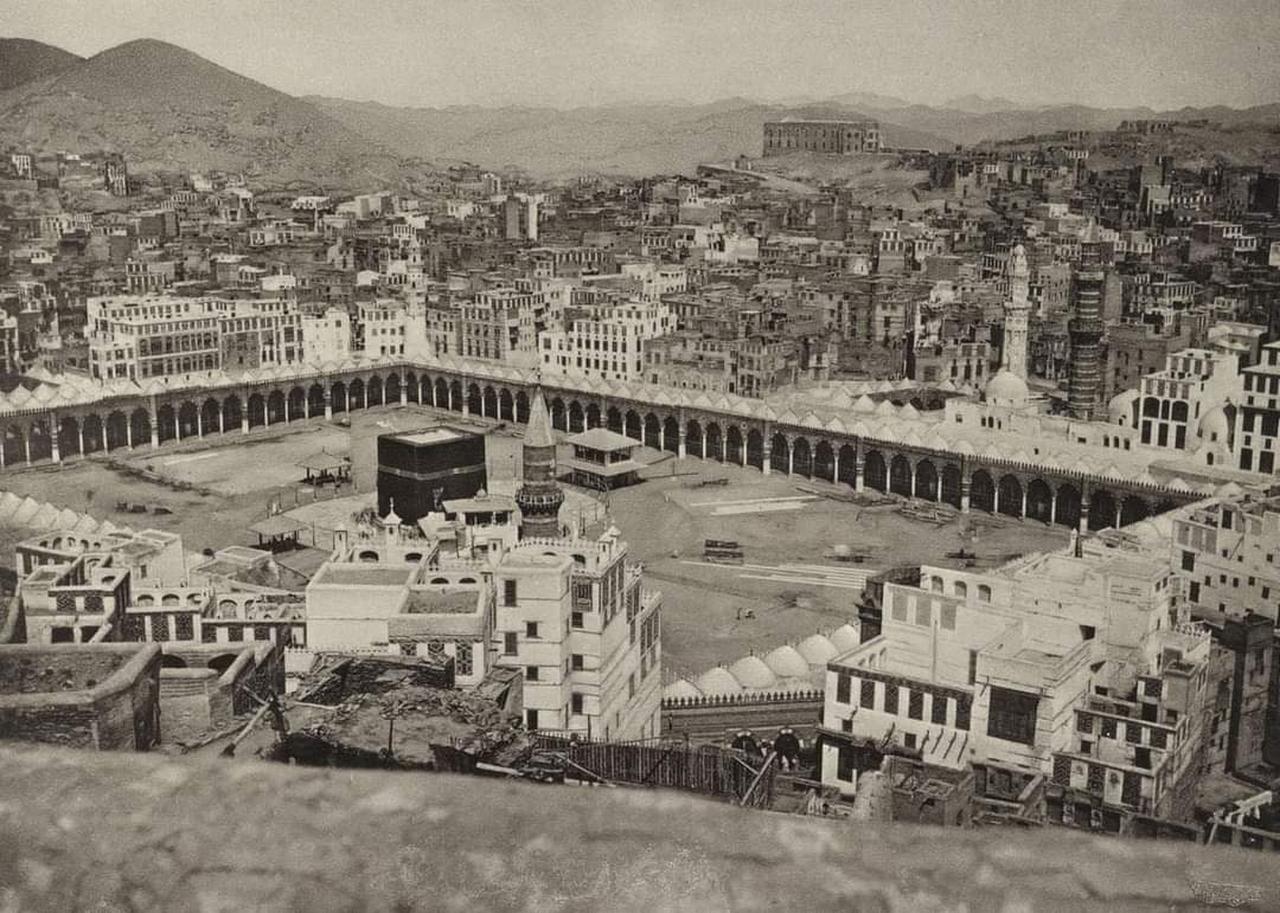

Abdulhamid II drafted a letter addressed specifically to the Moro Muslims of the Sulu Sultanate, directing them to submit to American authority and abstain from hostilities against U.S. forces. The message followed an unusual transmission route that emphasized the religious networks connecting distant Muslim communities: the sultan sent his correspondence to Mecca, where two Sulu chiefs were present and received the instruction before carrying it back to their homeland in the southern Philippines.

The intervention proved remarkably effective in its immediate objectives. Contemporary accounts documented that the "Sulu Mohammedans ... refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of (the American) army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty." This compliance came as a significant diplomatic victory for the American colonial administration at a crucial moment in the territorial expansion.

Lt.-Col. John P. Finley later provided detailed documentation of the sultan's reasoning and the broader context of the intervention. According to Finley's account, Abdulhamid II "caused a message to be sent to the Mohammedans of the Philippine Islands forbidding them to enter into any hostilities against the Americans, inasmuch as no interference with their religion would be allowed under American rule." The guarantee of religious freedom addressed the Moro population's primary concern about potential interference with Islamic practices under American rule.

U.S. President William McKinley personally thanked Ambassador Straus for the diplomatic achievement, providing a rare quantitative assessment of the intervention's military value. McKinley estimated that the Ottoman sultan's letter had "saved the United States at least 20,000 troops in the field," a figure that underscored the significant military and financial resources that would have been required to suppress a religiously motivated uprising across the southern Philippines.

President McKinley's personal thanks to Straus came with a clear assessment of what the intervention had accomplished. Finley later wrote about the financial stakes involved: "If the reader will pause to consider what this means in men and also the millions in money, he will appreciate this wonderful piece of diplomacy, in averting a holy war."

Despite the intervention's success and McKinley's private gratitude, the president chose not to publicly acknowledge the Ottoman Empire's role in his December 1899 address to Congress. This omission reflected the timing of congressional procedures, as the agreement with the sultan of Sulu had not yet been submitted to the Senate for consideration on Dec. 18, making public discussion premature.

Straus' memoirs later revealed additional diplomatic efforts, including a 1902 incident where he advised against military action in response to violence against American soldiers in the southern Philippines. Instead of deploying 1,200 troops as initially proposed, Straus suggested using "friendly datos" for peaceful resolution, referencing the framework established by the earlier Ottoman intervention.

While the sultan's letter successfully prevented Sulu Muslims from joining the initial Philippine insurrection, its protective effects proved temporary in the face of changing American policies. The diplomatic intervention coincided with the 1899 Kiram-Bates Treaty, which granted the Sulu Sultanate significant autonomy under American sovereignty, creating a framework that initially satisfied both parties' immediate interests.

However, when the United States unilaterally abrogated the Kiram-Bates Treaty in 1904, the diplomatic foundation that had prevented earlier conflict crumbled. The treaty's cancellation led directly to increased tensions and the outbreak of the Moro Rebellion, which lasted from 1902 to 1913 and involved some of the bloodiest fighting of America's occupation of the southern Philippines.

The rebellion that followed demonstrated the limits of religious authority in sustaining political arrangements. Despite the earlier Ottoman intervention, the Moro people launched sustained resistance against American colonial rule once the treaty protections were removed.

The conflict featured intense fighting, including battles at locations such as Pandapatan and around Lake Lanao, as American forces under commanders like John J. Pershing and Leonard Wood sought to impose direct military control over previously autonomous regions.