For years, the relationship between Türkiye and the EU has been defined by inertia. Accession talks have been frozen since 2018, the Customs Union remains a three-decade-old relic, and visa liberalization is a stalled promise.

Even though the EU recognizes Türkiye's importance in defense cooperation, political vetoes continue to block Ankara’s access to EU initiatives such as the Security Action for Europe (SAFE).

It is against this backdrop of strategic paralysis that EU Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos recently called for a "fresh eyes" approach, a hopeful pivot that must now contend with decades of accumulated friction.

This renewed engagement comes against the backdrop of Europe’s strategic reorientation since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

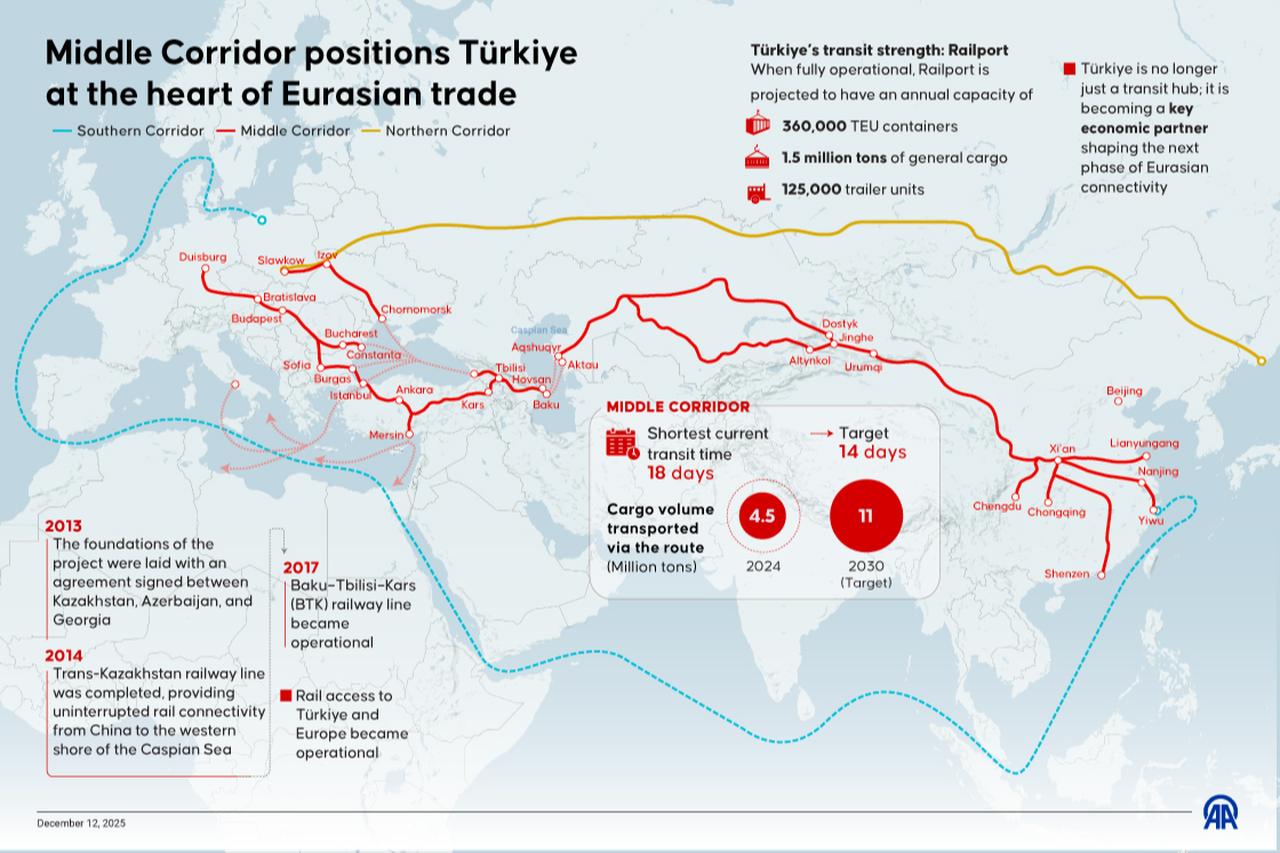

The war triggered a comprehensive diversification push—not only in energy and defense, but also in trade routes and connectivity. As Russia's Northern Corridor lost viability, the Middle Corridor—also known as the Trans-Caspian Transport Route—has gained strategic prominence. Cargo flows along this route have surged since 2022, shifting it from along-discussed alternative to a central pillar of Eurasian connectivity.

In this context, the EU has adopted a more strategic approach toward the Black Sea, the South Caucasus, and Central Asia. Its goal is twofold: to diversify trade routes and energy supplies, and to deepen economic and security ties with the region. This is not merely about safeguarding trade.

By limiting Russia’s regional influence and offering an alternative model to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the EU’s Middle Corridor strategy carries significant geopolitical weight. To strengthen the corridor, the EU Commission has published a comprehensive meta-study identifying priority investments and is seeking to boost financing through public–private partnerships.

For much of the 2000s, Central Asian states hesitated to pursue alternative routes, wary of Russia's reaction. Since 2022, however, disruptions in the north and Western sanctions have pushed these countries to actively seek new trade pathways as well.

This shift has intensified competition. Russia remains a potential spoiler, capable of undermining the corridor’s viability. China, whose BRI relies on much of the same infrastructure, is another competitor. A less openly discussed competitor is the United States, which has been advancing the so-called Zangezur Corridor under the framework of the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP).

U.S. Vice President JD Vance’s recent visits to Armenia and Azerbaijan highlight Washington’s growing interest in the region.

What Brussels now calls the Trans-Caspian Corridor is, in fact, the Middle Corridor that Türkiye has promoted since 2009.

The route connects Europe to Central Asia and China via Türkiye and the South Caucasus, linking railways and ports. Following the sharp decline in traffic through Russia’s Northern Corridor after 2022, a significant share of trade shifted to this alternative route, where trade has quadrupled.

Cargo volumes clearly illustrate this transformation: from just 586,000 tons in 2021 to 1.5 million tons in 2022, 2.8 million tons in 2023, and 4.1 million tons in the first 11 months of 2024. Projections for 2025, suggested that approximately 5.2 million tons could be transported, indicating continued growth.

While the corridor largely relies on existing rail and port infrastructure, major upgrades and new investments are required. The EU has identified key priorities and aims to expand trade not only through transport investments, but also by strengthening energy and digital connectivity. Priority areas include renewable energy cooperation, high-speed internet infrastructure and protection, and the digitization of customs processes to ease trade flows.

As Commissioner Kos emphasized, at the heart of the EU’s broader Connectivity Strategy lies Türkiye. Türkiye is positioned as a logistics, energy, and transit hub linking Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Ankara’s institutional engagement with the region dates back to its role in establishing the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States in 2009, later renamed the Organization of Turkic States in 2021. Major infrastructure milestones including the Trans-Kazakhstan railway, the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars rail line, and Istanbul’s Marmaray tunnel — have already turned the Middle Corridor from concept into reality.

Unlike the Chinese-led BRI, which relies on large-scale, state-driven infrastructure projects financed by institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the EU-led approach bypasses Russia and focuses on upgrading existing infrastructure. It emphasizes European Investment Bank (EIB) loans and public–private partnerships.

In this context, the EIB’s renewed engagement with Türkiye—including support for two renewable energy projects, each valued at €100 million—signals a meaningful policy shift.

For China, the EU’s growing interest presents both competition and opportunity. The corridor offers Beijing an additional gateway to global markets, reduces investment costs along the route, and further diversifies trade paths away from Russia.

Meanwhile, six months ago, in order to establish peace in the region and increase its economic influence, the United States mediated the TRIPP agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, ensuring leasing rights for the U.S. to develop the road. The proposed 43 kilometer road-and-rail corridor would run through Armenia and link Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave, thus opening a new East-West trade route bypassing Russia and Iran.

The Vice President’s visit to the two countries is heavily focused on developing economic relations with them. During Vance’s visit, a statement was also signed regarding an agreement between the U.S. and Armenia that would allow the U.S. to legally license nuclear technology and equipment.

Armenia is considering offers from U.S., Russian, Chinese, French, and South Korean companies to replace the country’s only Russian-built nuclear reactor.

For the EU, the corridor’s most immediate advantage is clear: it offers an East–West trade route that bypasses sanction-hit Russia. Compared to alternatives, it is also more secure. Trade through the Northern Corridor has been disrupted by sanctions, while southern maritime routes via the Suez Canal face growing risks from Houthi attacks.

Still, challenges remain. One major concern is sanctions evasion. Evidence of sanctioned technologies being re-exported through the region has prompted intensive EU diplomacy with Central Asian and Caucasus governments. Digitizing and modernizing customs procedures is essential to mitigate this risk.

Security threats also loom. Russia may seek to sabotage trade routes that exclude it. Its military activities in the Black Sea, including hybrid tactics such as shadow fleets and drifting mines, pose serious risks to maritime trade and energy infrastructure.

Strengthening coastguard capacities and monitoring systems is therefore critical—not only for Black Sea security, but for the resilience of regional trade.

Financing is another key issue. The EU has committed €10 billion to sustainable transport connectivity in Central Asia, while the EIB and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) have signed agreements with several regional governments. The involvement of multilateral financial institutions is welcomed locally, as it prevents the corridor from being dominated by a single geopolitical power.

However, higher transport costs along the route have led regional states to request loans with below market interest rates, and—drawing on the EU’s experience in the Western Balkans—to seek grant-based support alongside loans.

As efforts to end the Russia–Ukraine war continue, Russia is steadily losing its central role in regional trade, first due to sanctions, then due to diversification of trade routes. Even if the war ends, restoring EU–Russia trade, particularly in energy, will take years.

In this interim period, Türkiye stands out as an indispensable connectivity actor. Its geopolitical position, deep ties with regional states, modernized trade processes, and energy diversification efforts place it at the center of virtually every regional connectivity project.

The EU’s failure to prioritize the Middle Corridor for more than a decade now appears as a strategic blind spot. While EU-Türkiye accession talks remain stalled, a geopolitical environment marked by U.S. retrenchment and widespread trade diversification demands pragmatism.

The EU and Türkiye—already major trading partners—must overcome existing barriers, starting with the modernization of the Customs Union.

Equally important is recognizing that Türkiye must be included in all regional connectivity initiatives. The EU- and U.S.-backed Vertical Corridor for LNG and gas trade—from Greece through Eastern Europe—should not exclude Türkiye from LNG trade, but instead integrate with the country’s already robust LNG infrastructure.

Connectivity strategies between Allies must complement one another, not compete.