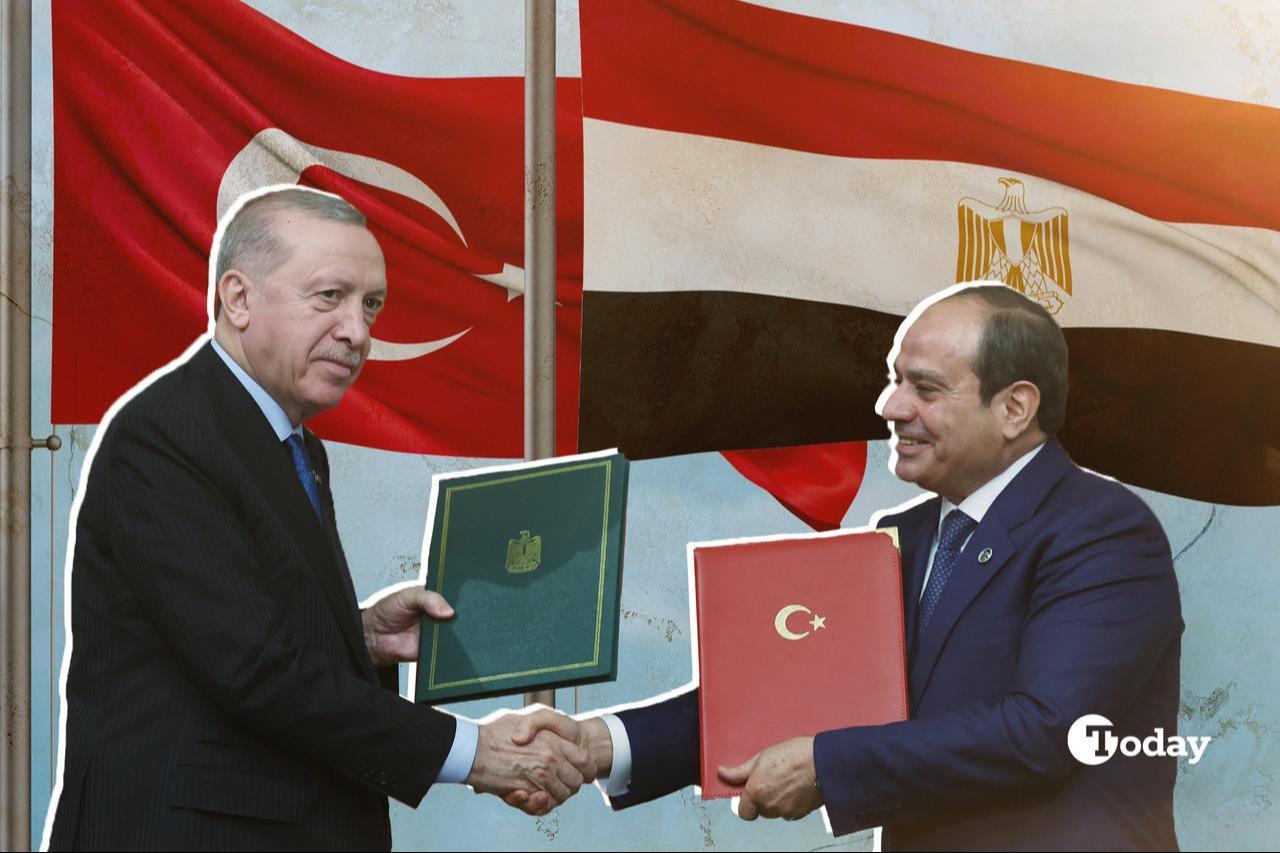

Instability across several regions in Africa and the Middle East has recently prompted an interesting and unforeseen geopolitical response: the emergence of deeper cooperation between once-antagonistic countries, such as Türkiye and Qatar, as well as Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

The precipitating events involved state decay and insurgency across an arc extending from the Horn of Africa and Libya through the Levant and to the Gulf, including Somalia, Sudan, Libya, Syria and Yemen. In each theater, various actors have sought to deconstruct national authority and establish sub-state power centers, supported, at different turns, by Russia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates and Israel. Consequently, cooperation among regional powers has emerged to oppose deconstruction and fragmentation.

One common thread across these conflict zones is religious: they are majority Sunni Muslim states facing deep division and crisis. Another is geopolitical: they occupy strategic areas sensitive to external powers due to the location of energy resources, transit routes, or contested borders. A third has been the emergence of a countervailing force in most of these areas aimed at bolstering national authority and state sovereignty: specifically, cooperation among the Turkish, Saudi, Egyptian, and Qatari governments to support the recognized national authorities.

For some in Washington, the response has caused more concern than the predicating instability. Is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia turning away from modernity and back toward retrogressive Islamism? Has the Muslim Brotherhood somehow seized new influence in Riyadh or Cairo? Is this the emergence of a new anti-Western Sunni Crescent to replace the waning Iran-backed Shia Crescent? A neo-Ottoman project by the Turks? Each question frames an interesting speculative narrative in its own right, and each has appeared in the Western press. Yet each lacks the basics of solid theory: contextual grounding, internal logic of the argument, testable hypotheses, and falsifiability. All represent some version of amateur psychoanalysis about what “the Sunnis” want—and generally, the answers are histrionic.

These concerns stem from a more basic “Sunni question” that has preoccupied many observers in the U.S., Europe, and the non-Muslim West since 9/11. Has the Sunni world from South Asia to the Atlantic become implacably anti-Western and systemically antagonistic to the West?

If the answer is yes, the politics of dividing, immiserating, invading, and blockading Sunni countries (except those with oil and gas) make a certain sense. If the region is viewed as a seething cauldron and source of trouble and discontent, then engagement should be focused on coercion and containment. Conversely, the emergence of cooperation among Sunni majority states to stabilize the fractured corners of their geocultural space seems a threat, and the West might be right to infer malign intent.

In other words, many in the West became fixated with the wrong Sunni question—captured most famously by Bernard Lewis’ What Went Wrong? Published in 2002, the book was criticized for factual inaccuracies, sweeping generalizations and mischaracterizations, as Juan Cole noted in a review that same year. It notably ignores Sunni-majority countries that have acted in strategic concert with the West—such as Türkiye in NATO, the Gulf states in energy markets, and Pakistan during the Cold War. Nevertheless, the Lewis framing became the dominant paradigm in Washington: the conviction that the "Islamic World" had become broken and antithetical to the West, perhaps irretrievably so.

In that sense, we can understand the West’s 15-year reluctance to meaningfully act against Assad in Syria, despite his threats and harm against the West as well as his own people. U.S. policies on Libya, Mideast Peace, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq in the current century were all marked by a muddled mix of force and distancing that makes sense only when we realize that the underlying vision was fatalistic and negative.

Western observers would be better served by a lens of geopolitical analysis—one that assumes pragmatism and self-interest take priority—rather than a culturalist or Orientalist lens that assumes irrationality rooted either in ideology or incapacity.

In this light, the “Sunni question” shifts; it becomes “what common interest might drive major regional powers from rivalry toward cooperation, and whether such a shift represents a threat or an opportunity for the U.S. and other Western powers?

The answer to the first part is that these powers seek to stabilize conflict zones within the “Sunni neighborhood”—areas defined by human suffering—so that they can join the evolving economic and political arrangements of the 21st century.

What the U.S. and U.N. have proven incapable of solving might now be solved through a combination of Gulf funding, Turkish military muscle and creative diplomacy. This means the construction of an axis of consolidation against a status quo based on fragmentation and strategic arson by external powers.

As for the second part, President Trump seems less wed to ideological predispositions and prevailing wisdom in Washington and more driven by the art of the possible. The Trump foreign policy encourages allied regional powers to take responsibility for their regions—Europe for Ukraine, Japan and Korea for the Pacific, Sunni powers for the Mideast.

Washington’s public intellectuals and analytic class may not have caught on yet, but the recent turn toward cooperation among our friends in the region fits perfectly with Trump’s vision of a reformed and sustainable global order.

Far from being a threat, it presents an opportunity to reduce ambiguity and cynicism in U.S. foreign policy and implement a pragmatic and commercially-oriented approach with concrete benefits for our national interest—as well as for the people of the region. To this Sunni question, Washington’s answer should be an emphatic “yes.”