Türkiye's highly integrated digital governance system, e-Devlet (e-Government), is under fire following revelations of an expansive forgery network. Official investigations, indictments and leaked details point to a systemic infiltration effort that not only compromised public trust but also exposed the vulnerability of the country’s digital identity infrastructure.

The breach has resulted in fake diplomas, driver’s licenses, and even altered citizenship records, many of them processed through forged digital signatures.

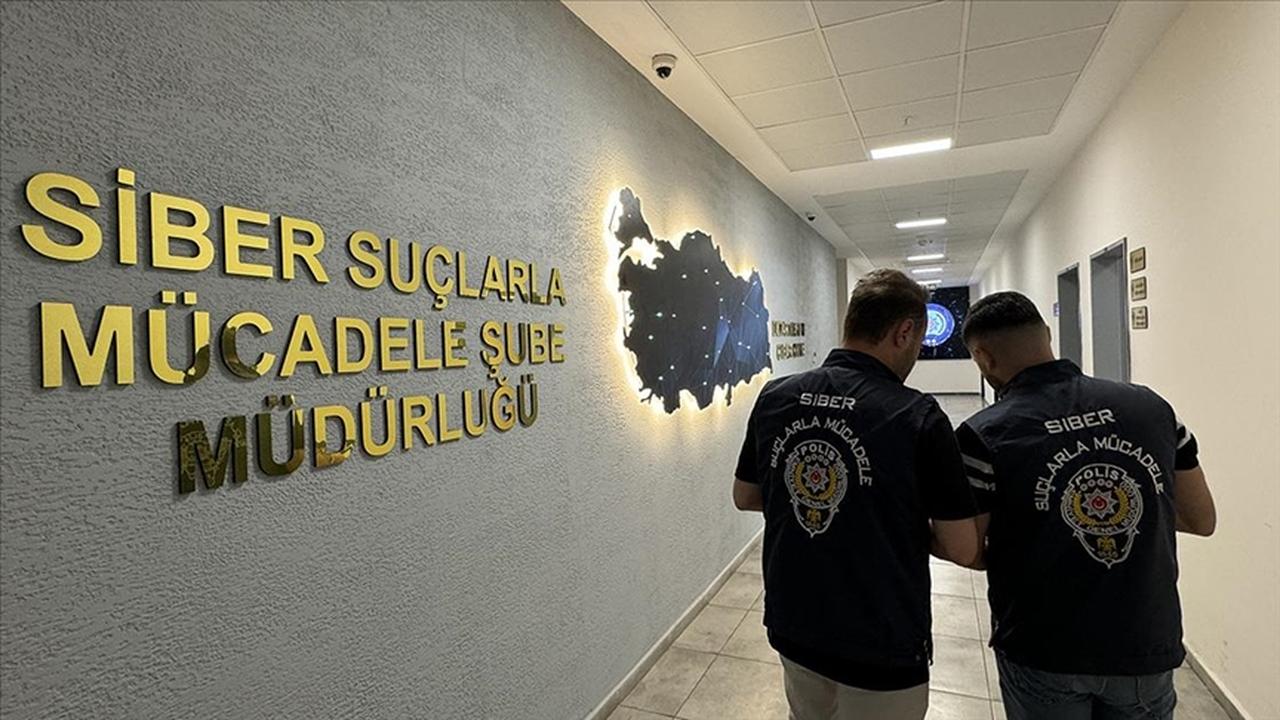

Authorities confirm that several perpetrators have already been apprehended, and some attempts were successfully blocked. However, the scale of the breach, which involves tampering with educational records and government credentials, suggests a long-running operation with institutional weaknesses.

The breach also raises the question of whether, if a local forgery ring can infiltrate Türkiye’s digital infrastructure, foreign intelligence services could pose a threat, signaling a full-scale national security crisis.

Public awareness of the breach began with a viral post on a Turkish consumer complaint site. The post, although not recent, is suddenly gaining traction, featuring complaints from individuals who had paid money in exchange for promises of fake diplomas registered in the e-Devlet system. Commenters claimed their diplomas would soon appear in the system with guaranteed approval; some even vouched for the service’s “legitimacy.”

Although initially dismissed as an internet oddity, the post drew renewed attention when linked to a wider network of digital forgery, prompting Turkish opposition parties, such as the Republican and People's Party (CHP), to raise formal parliamentary inquiries.

It was revealed that this was not a single isolated act but part of a structured effort involving forged educational credentials, manipulated state databases, and stolen citizen identities, which state forces are observing to understand completely and intervene at the root.

The central figure of the scheme appears to be Ziya Kadiroglu, a known figure with a prior criminal record, who reportedly led the forgery network. The methods varied from modifying driver’s license exam scores to assigning fake university diplomas for individuals who never completed or even attended higher education.

In some cases, the data of deceased earthquake victims or former students was repurposed to create new credential profiles.

The operation was made possible by replicating the e-signatures of public officials, including university rectors and senior bureaucrats. Once forged, these signatures enabled unauthorized access and modification of records within the e-Devlet infrastructure.

One notable claim was that digital keys used for property transactions within the National Real Estate Directorate were also targeted. The Ministry of Environment and Urbanization confirmed an attempted breach but insisted it had been intercepted before any damage was done.

Beyond the technical vulnerabilities, the scandal has reignited scrutiny over Türkiye’s recognition of foreign degrees, particularly from institutions in the Balkan region.

Critics allege that politically connected individuals obtained diplomas from unaccredited universities abroad and secured equivalency recognition from Turkish authorities. Comparisons were drawn to newly established domestic universities that reportedly lack professors or functional academic infrastructure.

The debate has cast a long shadow over the credibility of academic institutions, rekindling skepticism over the standards of higher education and public service qualifications.

A separate but related investigation revealed a corruption network involved in Türkiye’s citizenship-by-investment program. Under the program, foreigners can acquire citizenship by purchasing property valued at $250,000.

Investigators uncovered a ring that falsified real estate valuations, allowing applicants to meet the threshold on paper without actually investing that amount. In some cases, the $250,000 was temporarily transferred into a local account and then withdrawn immediately after the transaction was completed.

A total of 2,691 individuals are believed to have obtained Turkish citizenship through forged documents and fake bank receipts. Following the exposé, some citizenships were revoked, but questions remain over how many illegitimate applications remain undetected.

In a bizarre twist, one of the individuals implicated in the scandal is Abdulhamid Kayhan Osmanoğlu, a public figure who claims to be a descendant of Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II. Osmanoglu, known for marketing food products and often invoking Ottoman symbolism, was revealed to have received a forged history degree from Inonu University.

Despite the diploma’s cancellation, Osmanoglu denies all allegations, framing the controversy as a targeted campaign against his lineage by the ‘enemies of the Ottoman Empire,’ such as Theodor Herzl, in a reference that baffled many observers.

The e-Devlet breach has sparked broader fears about the integrity of Türkiye’s digital governance. While e-Devlet has revolutionized bureaucratic processes—enabling citizens to schedule hospital visits, change addresses, and access public services online—this is not the first time its data security has been compromised.

Past incidents include mass leaks through the E-BUS platform and allegations that sensitive data, including that of high-profile individuals, was being sold or accessed without consent. Journalist Ibrahim Haskologlu was detained in 2022 for publishing evidence of such breaches, including records of the Turkish president.

This context has intensified concerns over plans to digitize voting systems. Proposals for digital elections have been floated, with electoral board officials visiting Russia and Azerbaijan to observe electronic voting systems—raising eyebrows given the authoritarian nature of those regimes.

Experts warn that without stringent biometric security and transparent audit mechanisms, such proposals could open the door to further manipulation.

The scandal's implications extend far beyond fake diplomas or forged property sales. Experts describe it as a full-blown crisis of digital sovereignty. Türkiye lacks advanced safeguards like biometric cross-verification, immutable blockchain records, and AI-powered anomaly detection, which are some standards increasingly adopted in the EU’s eIDAS 2.0 framework.

The absence of these protections means that once malicious actors gain access to the system, they can tamper with identities, academic qualifications, and even electoral records with little resistance.

Critics argue that the damage is comparable to allowing counterfeiters into a national mint. The scale of forgery suggests that over 400 academics had their professional titles altered through digital manipulation.

As new layers of the scandal continue to unfold, from fake degrees to manipulated citizenships, public faith in Türkiye’s digital infrastructure is rapidly eroding. What was once hailed as a model of e-governance has now become a cautionary tale of overreach without oversight.

While some perpetrators are being prosecuted, the system’s repeated breaches and the lack of systemic reforms highlight a governance vacuum.

Türkiye now has to adopt internationally recognized data protection standards and introduce robust verification systems at a time when its digital future remains alarmingly fragile.