Türkiye’s restrictive import system for electronic components is drawing increasing concern from engineers, educators and entrepreneurs, who say the current framework is eroding the country’s capacity to participate in global innovation cycles.

Far from being a peripheral issue, the mechanics of customs and taxation policy are now seen as a central obstacle to Türkiye’s aspirations in defense, advanced manufacturing, and deep-tech sectors.

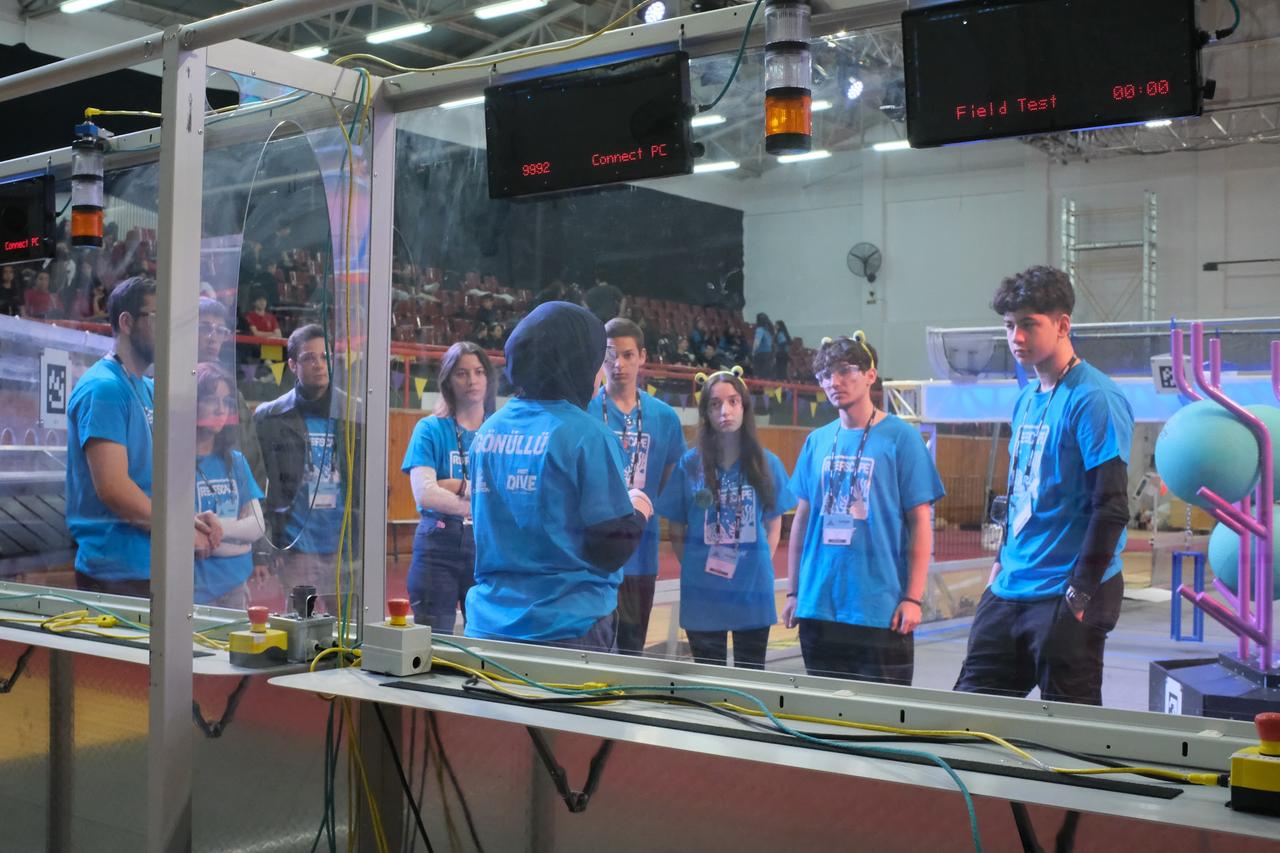

From robotics teams forced to build machines out of scrap to startups unable to iterate, the consequences are stifling innovation and halting research and development (R&D) projects across high schools, universities and early-stage tech ventures.

This week, public frustration surged after a well-known e-commerce entrepreneur stated on national television that Ankara should reduce its duty-free import threshold from $30 to zero, prompting backlash across social media.

Given that the Turkish government has made high-profile investments in creating a domestic R&D ecosystem, including events like Teknofest, such policy proposals increasingly appear at odds with national innovation goals and risk deepening structural contradictions in the country’s tech strategy.

The immediate problem is straightforward: imported electronic parts, even for educational and research purposes, are subjected to an accumulation of customs fees, value-added tax (VAT), regulatory certifications, and procedural delays that drive prices up by orders of magnitude.

Sourcing a $20 GNSS chip can incur customs broker fees, plus 20% VAT, up to 100% customs tax, and additional regulatory certifications—TSE (Turkish Standards Institution), CE (Conformite Europeenne), or TAREKS (Türkiye’s Product Safety and Inspection System)—which alone can add $700 to $2200.

The process takes four to twelve weeks, even before production begins. The result is a high financial barrier to entry for anyone trying to prototype and test new products.

In practice, the system prices out high school robotics teams, university labs, and early-stage startups, which are the very actors that typically form the backbone of any tech-based industrial policy.

Organizers of global robotics competitions say Turkish participants now often resort to collecting scrap parts to build machines that were once designed with globally sourced components.

The problem escalates when companies attempt to scale. In the early research and development (R&D) phase, startups often need to experiment with dozens of variants before choosing the right component.

But each import triggers a new round of bureaucracy.

Lead times stretch from four to twelve weeks, making rapid iteration, the hallmark of modern hardware development, almost impossible.

For many young firms, this is a dealbreaker before production even begins.

On the export side, firms face similar challenges. While domestic sales are simpler, international shipments reintroduce customs-related complexity, this time on both ends.

For firms hoping to sell into the EU or the U.S., the overhead can be significant enough to require setting up dedicated warehouses abroad.

A product that costs $50 to build ends up costing close to $140 once Turkish import taxes are factored in. Unless a product offers intellectual property exclusivity, it's unlikely to be competitive at that price point.

Despite the headwinds, some companies have found ways to adapt, although these workarounds often reinforce structural inequalities in the ecosystem.

Firms that dominate niche domestic markets may be able to absorb high import costs through high-margin sales.

Others fully outsource production to China, importing only final goods into Türkiye. In these cases, even packaging and firmware installation are handled abroad.

Another strategy is to move all R&D operations to jurisdictions where imports are less restrictive. While that can offer logistical advantages, it also raises long-term questions about Türkiye’s role in its own innovation economy.

A few of the local distributors have become go-to channels for many firms. But their inventories tend to focus on basic components.

For more specialized parts such as solenoids or mechanical actuators, availability is limited or nonexistent.

Even when procurement is possible, comparing delivery times, costs, and regulatory status consumes significant time and labor.

Scaling up from a single module to a full drone or robotics system multiplies the problem. Developers face similar restrictions on non-electronic parts, including carbon fiber tubes, servos, structural foams, and adhesives.

The result is a fragmented and inefficient innovation process, one that contrasts sharply with R&D cycles in the US, China, or even smaller EU countries.

Some actors are now advocating for a revised import model tailored specifically to R&D needs.

Under this proposal, registered companies in technology zones would be permitted to import components at 0% customs tax and 0% VAT, provided the goods are strictly monitored, inventoried, and only taxed if sold domestically.

Exported products would remain exempt, and when sold domestically, all applicable taxes would be enforced.

Advocates argue that such a model would reduce misuse while allowing firms to iterate quickly and lower their R&D costs.

Digital auditing tools and physical inspections, particularly within technoparks, could serve as enforcement mechanisms.

The result would be faster iteration cycles and higher survival rates for early-stage projects, without compromising regulatory oversight.

Technoparks do offer partial tax exemptions, but the mechanisms are slow, opaque, and often ineffective.

A typical process requires filing documentation, receiving approvals from oversight committees, securing VAT waivers, and then coordinating with customs.

The process can also take more than ten days and often does not fully offset associated costs. In many cases, companies are still paying the majority of the financial burden.

With few viable alternatives, some firms choose to outsource R&D altogether, relying on engineers in countries like Bulgaria or Germany to handle design and prototyping.

But this introduces a political and existential tension, as relocating core technical operations abroad gradually erodes the incentive to keep the company rooted in Türkiye.

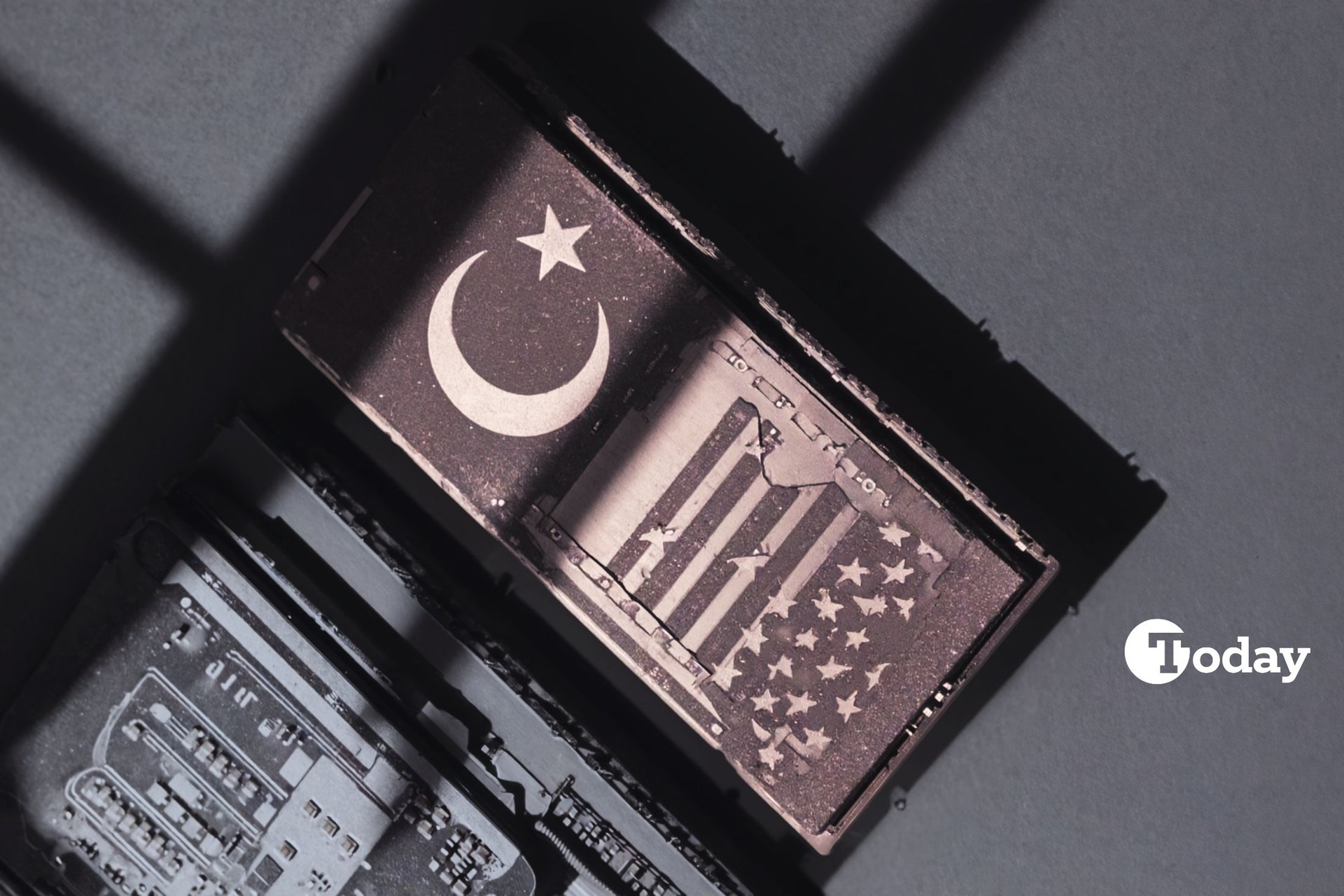

This is not merely a commercial concern; it has strategic implications as well. If Turkish entrepreneurs are forced to establish their critical operations abroad, the long-term development of a self-reliant, high-tech industrial base becomes harder to achieve.

What’s at stake is not just whether students can build robots or startups can prototype drones; it’s whether Türkiye will be a contributor to, or consumer of, the next generation of global technology.

The cost of inaction is clear. Unless reforms are made to reduce import costs for R&D and educational use, Türkiye risks isolating itself from the global innovation landscape.

Countries around the world are investing heavily in hardware autonomy, AI systems, robotics and defense tech.

Innovation depends on the freedom to experiment, fail, iterate and access parts. Right now, that freedom is being priced out of reach.