A new open-access study maps how Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania reclassified Muslim refugees’ homes and fields as “abandoned land” after 1878, asserted state ownership using Ottoman-era rules, and rapidly resold or reassigned those assets to Christian settlers—policies that reworked local economies and demographics for decades.

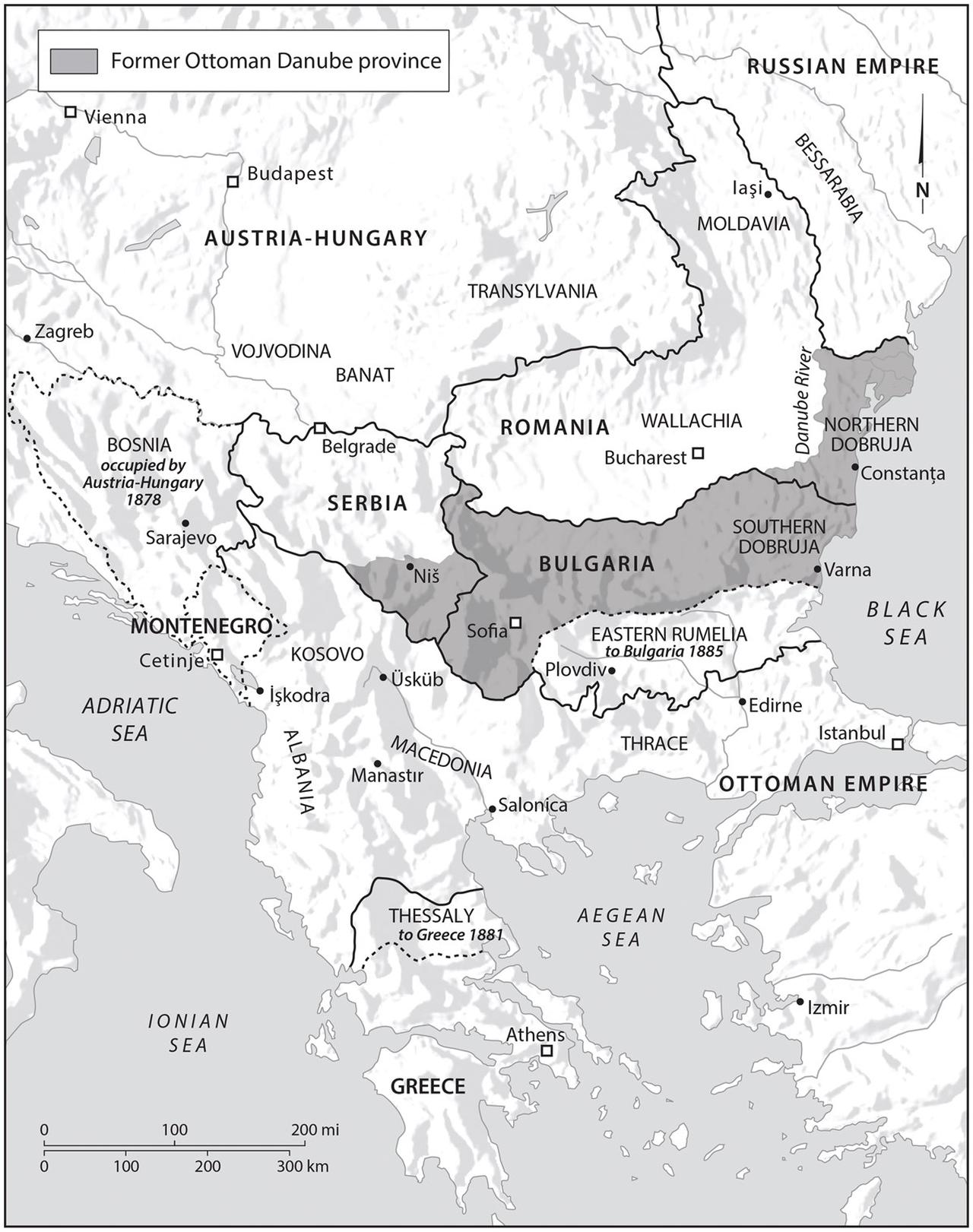

The Treaty of Berlin was signed on July 13, 1878, after the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877–78 and the subsequent revision of the San Stefano Treaty. It redrew borders in the Balkans, reducing the large Bulgarian state created at San Stefano and dividing it into the Principality of Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia, and Ottoman-ruled Macedonia. The treaty also placed Bosnia and Herzegovina under Austro-Hungarian administration and recognized the independence of Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania. It confirmed the continued, though diminished, authority of the Ottoman Empire in the region.

Rather than break with the past, the three governments built their land regimes on the Ottoman Land Code of 1858, which had reaffirmed state ownership (miri) of most farmland and granted cultivators a transferable right of use (usufruct).

The study argues that Sofia, Belgrade, and Bucharest leaned on this framework to reassert the state as the chief landowner and ultimate arbiter of disputes. (“Miri” refers to state land; “vakif” means charitable endowment; “usufruct” is the right to use and benefit from land without holding the freehold.)

Officials labeled fields, pastures, and buildings left by Muslims who fled the 1877–78 war as “abandoned,” which signaled that former tenants had forfeited ownership or use and that governments could appropriate and “redeem” the land.

Early targets were the properties of non-native Muslims—especially Circassians and Crimean Tatars—before the focus widened to vakif assets and large estates once held by native Muslim communities.

| Year | Group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1877 | Bulgarians | 43,180 | 25.2 |

| Muslims | 119,754 | 69.8 | |

| Others | 8,678 | 5.1 | |

| Total | 171,612 | ||

| 1880 | Bulgarians | 64,123 | 40.3 |

| Turks | 72,811 | 45.8 | |

| Tatars | 4,827 | 3.0 | |

| Others | 17,330 | 10.9 | |

| Total | 159,091 |

Demographics in Southern Dobruja─Sources:

Bulgaria’s 1880 Law on Circassian and Tatar Lands sorted refugee lands into private, communal, and state property, allowing some prior owners to reclaim plots the Ottoman state had taken without compensation, yet reserving wide discretion for redistribution.

A 1883 revision expanded exceptions so that land occupied by new immigrants or war veterans would not revert, while the treasury raised money by auctioning abandoned tracts and even selling land that prior owners could buy back.

| Year | Group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1877 | Bulgarians | 270,000 | 75.4 |

| Muslims | 77,500 | 21.6 | |

| Others | 10,800 | 3.0 | |

| Total | 358,300 | ||

| 1884 | Serbs | 343,270 | 96.8 |

| Albanians and Turks | 2,250 | 0.6 | |

| Others | 8,961 | 2.5 | |

| Total | 354,481 |

Demographics in the Nis Region─Sources:

Serbia’s 1880 law for the Nis region defined a standard farm plot (ciftlik) at 70–80 donum (about 16–19 acres) for prime land and sought to confirm peasants’ ownership—if they could buy out pre-1878 owners. Many could not.

Belgrade took a loan in 1882 to compensate landowners, leaving cultivators indebted to the state, repayable with interest over 15–20 years.

| Year | Group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1878 | Romanians | 46,504 | 20.6 |

| Bulgarians | 30,177 | 13.4 | |

| Russians | 12,748 | 5.6 | |

| Tatars | 71,146 | 31.5 | |

| Turks | 48,783 | 21.6 | |

| Circassians | 6,994 | 3.1 | |

| Others | 9,340 | 4.1 | |

| Total | 225,692 | ||

| 1882 | Romanians | 49,724 | 29.8 |

| Bulgarians | 30,349 | 18.2 | |

| Russians | 16,668 | 10.0 | |

| Tatars | 31,114 | 18.7 | |

| Turks | 24,247 | 14.6 | |

| Circassians | – | – | |

| Others | 14,710 | 8.8 | |

| Total | 166,812 | ||

| 1912 | Romanians | 216,425 | 56.9 |

| Bulgarians | 51,149 | 13.4 | |

| Russians | 35,859 | 9.4 | |

| Tatars | 21,350 | 5.6 | |

| Turks | 20,092 | 5.3 | |

| Circassians | – | – | |

| Others | 35,555 | 9.3 | |

| Total | 380,430 |

Demographics in Northern Dobruja─Sources:

Romania reasserted state ownership in northern Dobruja in 1880 and, in 1882, offered much of that land for sale to citizens—either current tillers or incoming settlers.

Buyers could obtain full title by paying one-third of cadastral value, set as the equivalent of the former tithe; later, they could cede one-third of their plots to the state to secure ownership.

Across the northern Balkans, villagers contested the status of these properties as state land and asked to reclaim what they considered communal or ancestral plots.

In Kula district, farmers warned in 1880 that if land was not entrusted back, they would be forced to scatter again; elsewhere, petitioners pleaded, “Otherwise, our situation is abysmal.” Communities also argued for practical reuse—such as dismantling empty Circassian houses to build schools and churches.

Authorities did not only auction land. In Serbia, the state rented out hundreds of abandoned Muslim properties and collected harvests.

By late 1878, officials counted yields of more than £11 million of hay, almost 6 million pounds of straw, and £4 million of wheat—valued at over 1,319,080 kurus (Ottoman lira)—while also leasing 301 former Muslim properties whose declared market value approached 34,338 kurus.

Return was restricted from the outset: in 1878 the Russian head of Bulgaria’s provisional administration allowed Muslim returnees but barred Circassians, citing fears of reprisals and referring to wartime atrocities.

Their abandoned lands were initially earmarked to house native Muslims, yet later governments prioritized other goals. More broadly, the article shows that Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania used appropriated lands for internal colonization by settling Christian immigrants and tightening resale rules to bind them to the soil.

Treaty-mandated property commissions proved uneven. The Bulgarian-Ottoman body stalled without authorizing compensation, while Serbia declined a bilateral format.

In Dobruja, an Ottoman-Romanian commission logged 2,611 claims covering about 504,046 decare and, in 1908, Bucharest agreed to a lump-sum ₣75 million—money the Ottoman side never received, keeping the dispute alive into the next decade.

The study contends that contestation over refugees’ property was central to state-building, fine-tuning mechanisms of dispossession and redistribution, and setting the limits of who could own land.