The Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylia (MAK) formally proclaimed the independence of the Federal Republic of Kabylia during a ceremony in Paris on Dec. 14, 2025. Led by Ferhat Mehenni, the movement self-describedly seeks to establish a secular, pro-Western state independent of the central government in Algiers.

The so-called independence ceremony took place in a private hotel near the Arc de Triomphe, France, with a large audience of activists, movement leaders and several figures from other countries.

The government in Algiers, which designates the MAK as a terrorist organization, viewed the event as a major provocation.

Currently holding no territory, Kabylia’s claimed borders encompass critical infrastructure, including the Bejaia oil terminal, as the declaration carries significant weight regarding energy security. Independence advocates argue that Kabyle control over these assets would diversify energy corridors to Europe and reduce regional reliance on the current Algerian state apparatus.

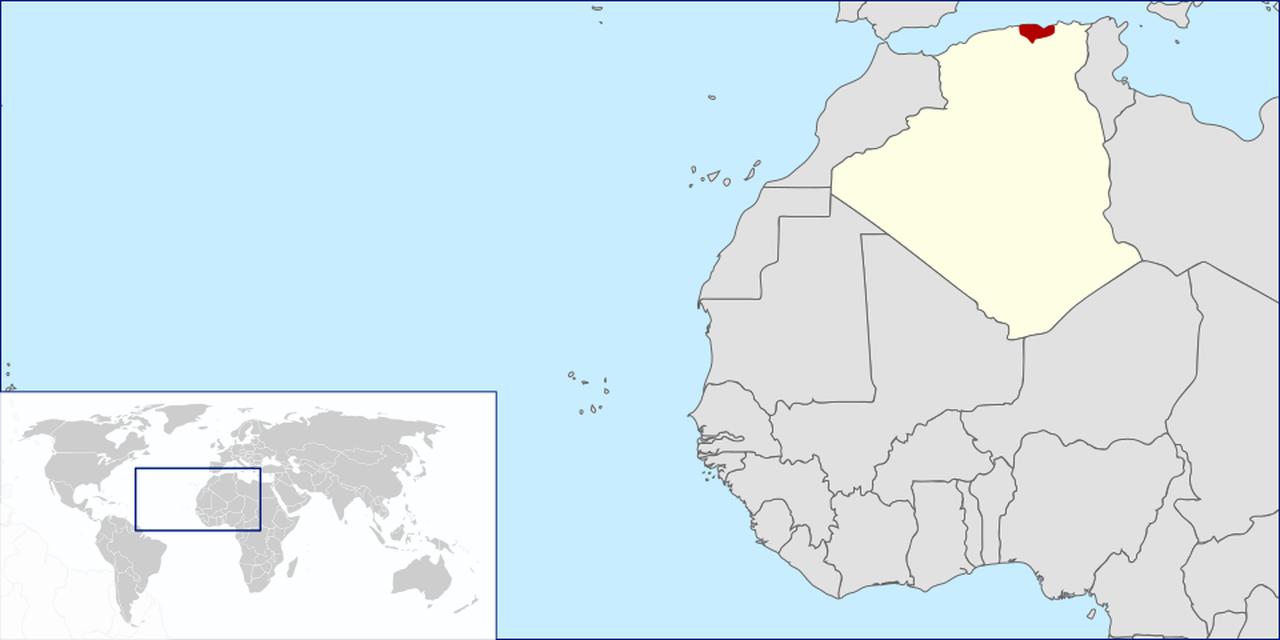

Kabylia is a mountainous region in northern Algeria inhabited predominantly by Amazigh (Berber) populations, estimated at between 3 million and 4 million people. The region has long been an integral part of the Algerian national fabric and played a decisive role in the country’s anti-colonial struggle.

The regional activism intensified after the 1980 “Berber Spring” and again during the 2001 Black Spring protests, both of which left deep scars in the collective memory of the region.

Algiers argues that the MAK’s narrative deliberately conflates cultural pluralism with political fragmentation. In recent years, Algeria has taken steps to constitutionally recognize Amazigh identity and language nationwide, undermining claims that Kabyle culture faces existential repression.

Electoral participation, civil society activity, and local politics consistently demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of Kabyle citizens pursue their demands within the framework of the Algerian state.

Israel has a doctrine of maybe yet not announced alternative regimes across the MENA. As they host alternative Iranian leadership and give them a platform often, the MAK has cultivated significant ties with Israeli officials.

Given Algeria's historical opposition to Israel due to its colonial past, many Israeli analysts openly argue that recognizing the movement carries little cost diplomatically for the country.

Though too early yet, from Tel Aviv’s perspective, Algeria is already firmly positioned within an anti-Israel bloc, leaving little room for diplomatic cost. Support for Kabyle self-determination is framed less as ideological solidarity and more as strategic pressure against a hostile regional actor. This calculus mirrors Israel’s past engagement with minority movements across the Middle East, leveraging peripheral alliances to offset regional isolation.

During his 2017 presidential campaign, Emmanuel Macron—then a "political outsider"—signaled a historic shift by labeling France’s colonial actions in Algeria "crimes against humanity," a gesture that promised a new era of reconciliation. However, by 2021, under pressure from a surging far-right, Macron’s rhetoric shifted toward denouncing "memorial rent," accusing the Algerian establishment of politicizing historical grievances for domestic gain.

Since that pivot, bilateral relations have entered a seemingly bottomless downward spiral. The depth of this rift is perhaps best captured by Algerian writer Kamel Daoud, who noted that younger generations of Algerians now harbor a more intense resentment toward France than their parents, who actually lived through the colonial era.

Adding to these tensions is France’s decision to provide a platform for the Kabyle separatist movement and its refusal to extradite the group's leadership to Algiers, a move the Algerian government views as a direct violation of its sovereignty.

Last August, French President Macron also requested to tighten visa requirements of Algerian diplomats and government representatives, suspending a 2013 bilateral deal over alleged “growing migration difficulties”.

For France and Israel, Kabylia is less a viable state project than a pressure lever, useful precisely because it unsettles Algeria without requiring immediate commitments.

The declaration in Paris may not redraw borders, but it further hardens fault lines already running through Franco-Algerian relations. In a Mediterranean space increasingly shaped by energy insecurity, great power competition, and unresolved colonial memory, Kabylia has become more than a regional question. It is now a geopolitical signal.