Today, from Baghdad to Damascus, Aleppo, Beirut and Sanaa, Iran’s presence is visible not only in politics but also in the social and cultural fabric of these cities.

Tehran has effectively placed Shia Islam at the center of its foreign policy, not merely as a matter of faith, but as a strategic tool to advance its national interests.

Unlike the narratives that either idealize Iran as an anti-imperialist power or demonize it as a sectarian actor, the reality is more pragmatic: Iran functions as a nation-state guided by its own interests, with Shia ideology serving as an instrument of influence rather than its sole purpose.

The Middle East is once again witnessing a defining chapter in the long history of Shia expansion.

This period, which some describe as the “third rise” of Shiism, follows the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979. This turning point reshaped Iran’s role from a nation-state seeking modernization to a revolutionary power pursuing regional influence through religion.

The rare opportunity to counter Iran’s regional expansion must not be lost to the familiar trap of asymmetry, allowing Tehran to re-entrench itself. In contrast, others hesitate to act, which can only be seized by fully understanding the pillars of its strategy.

The roots of Iran’s modern identity trace back to the collapse of the Qajar dynasty and the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi in the 1920s. As the Ottoman Empire disintegrated, Reza Shah sought to emulate the newly formed and relatively stabilized Republic of Türkiye.

His famous 1934 visit to Ankara marked a symbolic moment. Inspired by Turkish reforms, he attempted to impose modernization at home, introducing measures such as the Kashf-e hijab—the unveiling of women—in 1936.

However, these top-down reforms provoked fierce backlash from the Shia clergy.

The tension culminated in the 1935 Gevher Shad massacre in Mashhad, where police opened fire inside the Imam Reza Shrine, killing hundreds of protesting clerics and students.

This event deepened the rift between the monarchy and the religious establishment, sowing the seeds of the clerical awakening that would later fuel the 1979 revolution.

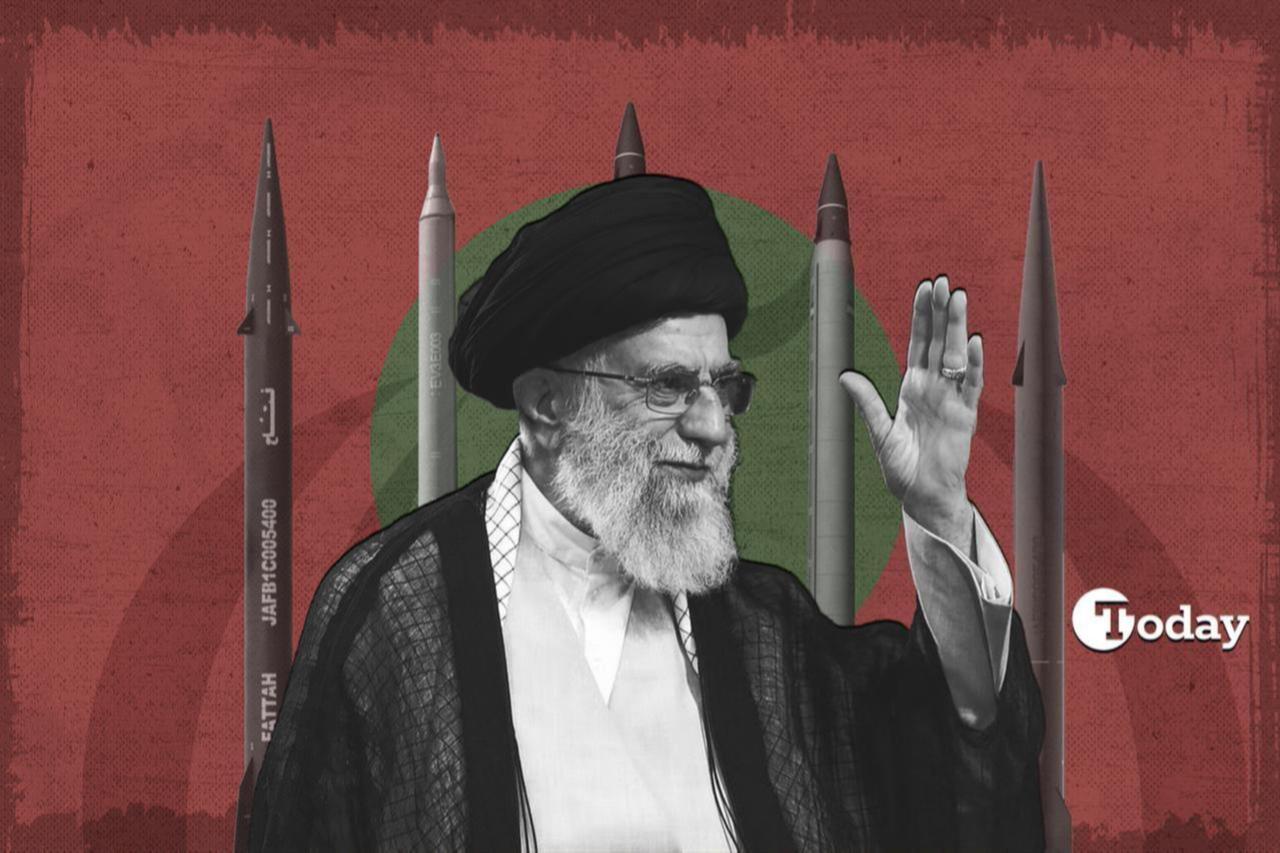

When Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his followers established the Islamic Republic, they fused revolutionary zeal with traditional Shia narratives.

Two central themes emerged as enduring pillars of Iran’s outreach across the Muslim world: the cause of Palestine and the veneration of the Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) family (Ahl al-Bayt).

The appeal of the Ahl al-Bayt remains one of Iran’s most effective soft-power tools. While Sunnis across the region respect figures like Imam Ali and Imam Hussein, Iran has transformed their remembrance—particularly the mourning rituals of Ashura—into a political and emotional bridge to the wider Muslim world.

Yet these observances often carry implicit sectarian undertones, leading to tensions and reinterpretations in Sunni-majority societies.

Iran’s regional project mirrors the historical trajectory of cities that once symbolized Sunni scholarship but now reflect Shia dominance.

Baghdad, once the intellectual capital of Sunni Islam and home to historical figures like Imam Abu Hanifa and Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, has over the past century undergone a profound sectarian shift.

Through wars, power transitions, and militia influence, the political and religious tone of Iraq’s capital is now decisively Shia.

The transformation is not limited to Iraq. In Lebanon, Iran-backed Hezbollah emerged during Israel’s 1982 invasion, evolving from a resistance movement into a state within a state.

With Iranian funding and training, Hezbollah extended its control over vast areas of Beirut, Tyre and Baalbek, maintaining its influence until Israeli and regional pushback weakened its reach.

Iran’s Shia project operates alongside other ideological tools in the region’s power competition.

Zionism serves as Israel’s organizing force, while Iran’s counterpart is Shiism, both mobilizing collective identity for geopolitical leverage.

This sectarian and national competition has produced an asymmetric landscape where Tehran projects influence through religious networks, while other states rely on military or economic partnerships.

This asymmetry is also visible in Iran–Türkiye dynamics. While Turkish or Sunni institutions and sentiments face restrictions within Iran, Tehran’s supporters freely enjoy their organizations and can have their narrative shared.

The recent establishment of Shia cultural centers in Türkiye, such as the expansive Zeynebiye complex in Istanbul, is one example of that.

The imbalance, even though it might not be planned directly, reflects Tehran’s long-term strategy of expanding its soft power footprint while limiting reciprocal Sunni influence at home.

Four historic Sunni capitals—Baghdad, Damascus, Beirut, and Sanaa—now form the axis of Iran’s regional reach.

Each represents a distinct phase of Tehran’s influence: Iraq through political dominance, Syria through military alliance, Lebanon through proxy networks, and Yemen through ideological alignment with the Houthis.

Damascus, once a cradle of Sunni scholarship and home to figures like Imam Nawawi, has fallen under Iranian sway until the incomplete resolution of the Syrian civil war.

At the heart of Iran’s ideological narrative lies Jerusalem, a city that serves both as a spiritual compass and a political instrument in Tehran’s regional vision.

Within Iranian discourse, Jerusalem is not merely a symbol of Muslim sanctity or resistance to Israel—it is also a prism through which Iran defines its role in the Islamic world.

Yet the historical figures tied to the city’s Islamic past represent the very leadership traditions that Iran’s revolutionary ideology sought to transcend.

The city’s most celebrated liberators for Turks and most of the Muslims—Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, and Sultan Selim I—each mark pivotal moments of Muslim ascendancy.

Umar’s conquest of Jerusalem in 638 established the city’s first Islamic governance, embodying justice and inclusion at a time when sectarian divisions had not yet crystallized. For Sunnis, Umar remains the archetype of the righteous ruler who spread Islam through moral authority rather than compulsion.

For Iran, however, he represents the early caliphate that sidelined the Shia lineage of Ali ibn Abi Talib—a foundational grievance in Shia theology.

Centuries later, Salah ad-Din ended the Shia Fatimid Caliphate in 1171 by overthrowing the dynasty.

Ottoman Sultan Selim's victory over the Safavids in 1514 not only curbed Shia expansion into Anatolia and the Arab lands but also set the boundaries of Sunni political authority for centuries.

Thus, Jerusalem occupies a dual space in the Iranian narrative. Publicly, it is championed as the emblem of Muslim solidarity against Israel and Western dominance—a cause Iran has used to mobilize Shia and non-Shia groups alike.

Yet at a deeper level, the city’s Islamic history reflects Iran’s enduring tension with the Sunni political tradition.

The heroes of Jerusalem’s past are not Iranian icons but leaders whose victories mark moments when Shia expansion was halted.

This ambivalence explains why Iran’s rhetoric on Palestine, while central to its regional strategy, often carries a dual purpose: projecting Islamic unity outward while consolidating Shia legitimacy inward.

Countering Iran’s influence requires more than opposition; it demands comprehension.

Tehran’s strategy—rooted in ideological flexibility, proxy networks, and the calculated use of Shia identity—has allowed it to create new asymmetries. To ignore or oversimplify this playbook is to invite its resurgence in new forms.

The current regional landscape presents a rare moment—a fleeting window in which Iran’s expansionist posture can be meaningfully challenged.

Shifts in regional alignments, coupled with Washington’s renewed assertiveness over Tehran’s nuclear activities, have created conditions that limit Iran’s maneuvering space for the first time in years.

Yet this opportunity will only bear fruit if approached through a reading of Iran’s tools, methods, and narratives with the precision they deserve; the Islamic Republic will once again adapt, recalibrate and reclaim lost ground.