Afghanistan’s stance on slavery has undergone a dramatic legal reversal in recent years. Under the Taliban’s current governance, since 2021, the country’s new legal code has reintroduced the term “slave” in official law–a move unprecedented in over a century of Afghan legislation.

In early 2026, the Taliban authorities approved a new criminal code that, in several articles, explicitly distinguishes between a “free” person and a “slave,” effectively recognizing slavery as a legal category.

For example, Article 15 of this Taliban code states that if a crime does not mandate a fixed (hudud) punishment, it shall be punishable by discretionary penalty (ta’zir), “whether the perpetrator is free or a slave”. Human rights organizations have warned that by using the term “slave” in its laws, the Taliban are legitimizing a status that had long been abolished in Afghanistan. This development stands in stark contrast to the country’s previous legal framework: for decades prior, Afghan law–including constitutions and penal codes–did not recognize slavery in any form.

Importantly, the Taliban have not openly proclaimed a return to slave-holding as an institution; however, the mere inclusion of “slave” in legal texts is symbolic and significant. It signals a departure from Afghanistan’s international commitments and the consensus of the Muslim world in the modern era, which views slavery as incompatible with human dignity and Islamic ethics.

In fact, worldwide, including in Islamic countries, the very concept of slavery today is considered illegitimate and condemned. The Taliban’s revival of this terminology has therefore raised concerns both domestically and abroad. To understand how Afghanistan arrived at this point, it is essential to explore the legal history of slavery in the country, from its roots in law and historical practice, through its abolition in the early 20th century, to the recent changes under Taliban rule.

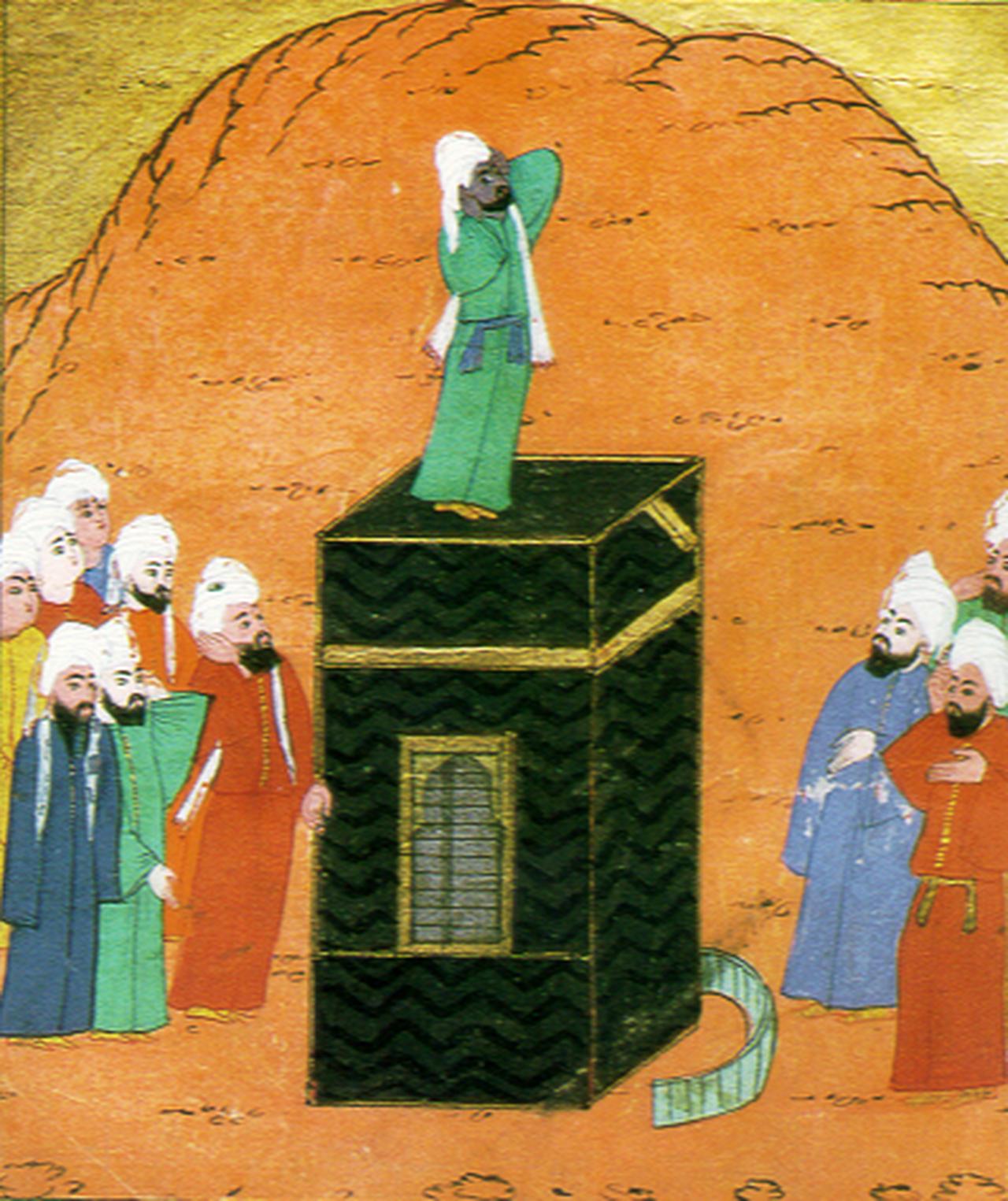

In the broader context of Islamic law, classical Shariah did permit slavery under limited conditions, primarily as a result of war. Both Sunni and Shi’a jurists historically agreed that non-Muslim captives taken in a legitimate war could be enslaved, whereas free Muslims could not be enslaved. Islamic jurisprudence from the seventh century onward developed detailed regulations for the treatment of slaves, ensuring they had certain rights and encouraging their manumission (freedom) as a virtuous act.

The Quran urged humane treatment of slaves and set out pathways for slaves to earn freedom (for instance, Quran 24:33 encourages masters to allow slaves to buy their liberty). Owning slaves was an accepted norm in pre-modern Muslim societies, including the regions that now comprise Afghanistan, but it was tempered by religious guidelines: it was impermissible to enslave a free person of the Islamic faith, and abuse of slaves was forbidden, with jurists even prescribing penalties for cruel owners.

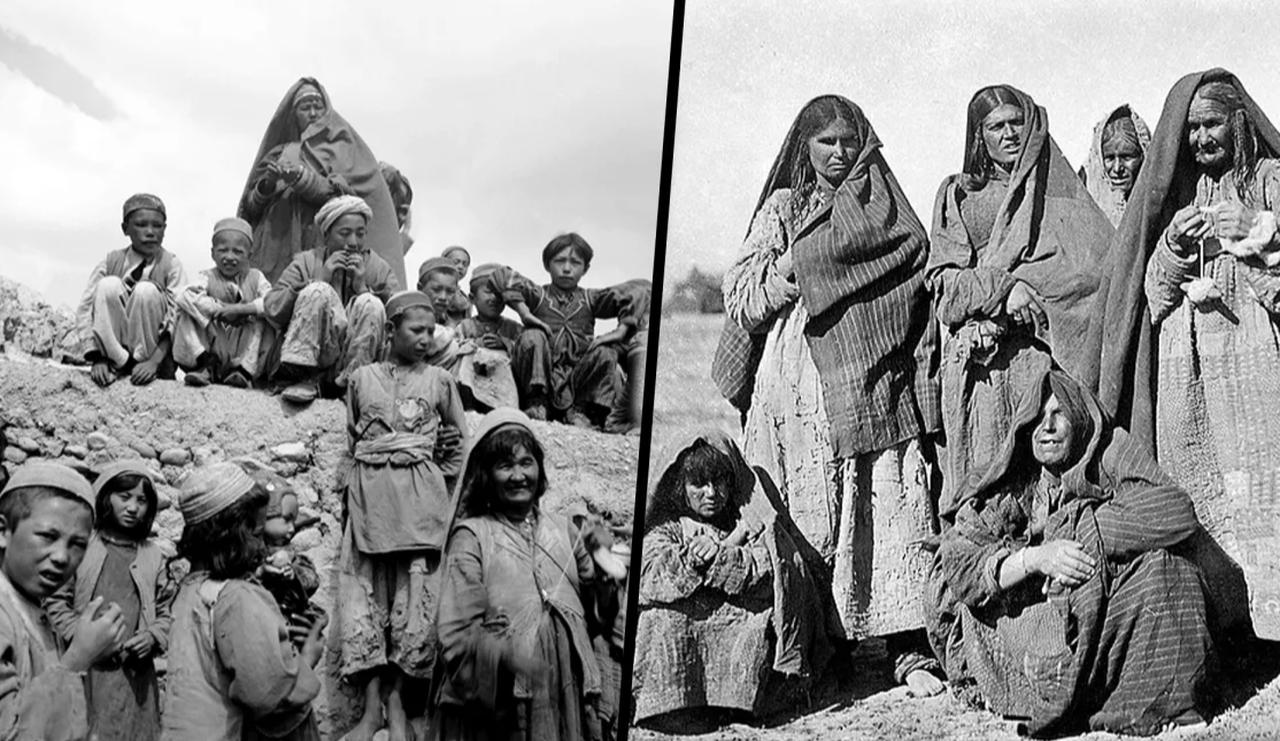

Within Afghanistan’s territory, which historically lay along Central and South Asian imperial routes, slavery was practiced in line with these broader norms. Enslaved people in Afghan history were often war captives or debt bondsmen, and typically employed as household servants, laborers, or soldiers. Unlike the plantation slavery once seen in the Americas, large-scale agricultural slavery was rare in Afghanistan due to different economic conditions. That said, slavery in the region could still be harsh, and instances of slave trading occurred, especially in the 19th century before abolitionist reforms. Notably, the late 19th-century Afghan wars saw egregious cases of enslavement. During the Hazara War of 1891–1893, Emir Abdur Rahman Khan brutally crushed the Hazara ethnic minority; contemporary accounts estimate that more than half of the Hazara population was killed, displaced or forcibly taken into slavery in that period. Victorious Afghan forces sold thousands of Hazara men, women, and children as slaves in markets in Kabul and Kandahar. This tragic episode underscored how slavery, though traditionally regulated by Islamic law, was used as a tool of repression and was deeply woven into Afghanistan’s pre-modern social fabric. By the turn of the 20th century, however, attitudes were beginning to change as global and local pressures mounted to end the practice.

A major turning point came with the reign of King Amanullah Khan (1919–1929), the reformist Afghan monarch who led the country to full independence and sought to modernize its laws. Influenced by contemporary movements in the Muslim world (such as the late Ottoman reforms) and a desire to join the international community of nations, Amanullah championed a broad agenda of legal and social change. Abolition of slavery was a centerpiece of his reforms.

Afghanistan’s first constitution, promulgated as the Basic Code of 1923, expressly banned slavery throughout the country. Article 10 of this 1923 constitution declared: “In Afghanistan, the principle of enslavement is completely abolished. No one, whether man or woman, may employ another as a slave.” This sweeping provision was the first national law in Afghan history to categorically prohibit slaveholding and the slave trade. It reflected Amanullah’s commitment to Islamic modernism–framing the ban in terms of justice and the public interest–while reassuring that it did not violate Islamic principles. In fact, Amanullah’s advisers, many of them Islamic scholars, argued that ending slavery was consistent with Shariah’s spirit of human equality and the Quranic encouragement of freeing slaves.

The 1923 abolition of slavery in Afghanistan was met with approval by reformists and signaled Afghanistan’s entry into a new era of law. One Western historian notes that among Amanullah’s many progressive decrees were “the opening of schools for girls, stronger legal protections for non-Muslims, the banning of slavery, and the criminalization of animal cruelty.” These changes showed that Afghanistan, an independent Muslim-majority kingdom, could reconcile Islamic governance with the global movement against slavery. Polygamy was also discouraged and other social ills were targeted, but the outright ban on slavery was especially bold given that some conservative elements of society initially resisted certain reforms. Despite internal opposition that eventually contributed to Amanullah’s abdication, his abolition of slavery endured as part of Afghanistan’s legal fabric.

Amanullah’s policy was further solidified under his successors. In 1931, during the reign of Mohammad Nader Shah, Afghanistan adopted a new constitution (the Basic Principles of the State of Afghanistan) that maintained the ban on slavery. Article 11 of the 1931 constitution explicitly states: “In Afghanistan, the principle of enslavement is prohibited. No one, whether man or woman, may employ another as a slave.” This clause reaffirmed the 1923 language, embedding anti-slavery firmly in Afghan law. From that point forward, every Afghan constitution upheld the abolition of slavery. Subsequent charters–including the 1964 constitution of the constitutional monarchy, the 1977 and 1980 documents during the republic and communist periods, and the 2004 post-Taliban constitution–all emphasized the equality and freedom of all citizens. In practice, by the mid-20th century, slavery as an institution had effectively vanished in Afghan society. Owning or trading slaves became socially unacceptable and legally impossible, and the concept of slavery “ceased to be a subject of discussion” in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s abolition of slavery was not only a domestic milestone but also part of a broader international trend. In the decades after Amanullah’s decree, Afghanistan joined several global treaties and initiatives outlawing slavery. It became a state party to the 1926 Slavery Convention (originally convened by the League of Nations) by formally acceding to it in 1954. This convention bound Afghanistan to prevent and suppress the slave trade and to cooperate internationally to end slavery in all its forms.

Furthermore, Afghanistan acceded to the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery in 1966, which reinforced commitments to eliminate practices like serfdom, debt bondage, and child servitude. By the late 20th century, Afghanistan had also ratified modern human rights instruments that prohibit slavery and forced labor, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) (Article 8 of which bans slavery and the slave trade in all forms). In the Afghan legal system of the 1960s–2010s, any form of enslavement or human trafficking was a criminal act, often prosecuted under laws against forced labor, kidnapping, or human trafficking.

Crucially, these anti-slavery measures were in harmony with the prevailing view across the Muslim world. By the mid-20th century, all independent Muslim-majority states had outlawed slavery, with countries like Saudi Arabia (1962) and others abolishing it under both international and internal pressures.

Islamic scholars and jurists of modern times largely reached a consensus that slavery is incompatible with Islamic ethics and the intent of Shariah in the contemporary era. For instance, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (adopted by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in 1990) explicitly prohibits slavery in Article 11, affirming the dignity and equality endowed by God to every person.

Prominent Islamic authorities have stated that ending slavery aligns with the core goals of Islam, since Islam’s original push was to gradually free slaves and uphold justice. As one modern Islamic jurist put it, “Islam totally objects to and fights all forms of slavery … Now, slavery has been abolished by international conventions, and this goes in line with the goals of Islam.” In short, by the 21st century, there was no contention–legally or theologically–that slavery should remain abolished.

Afghanistan, as a Muslim-majority nation, was part of this global moral and legal consensus, having “accepted and acceded to all international instruments related to the abolition of slavery”. This makes the recent Taliban-era changes even more striking and controversial.

When the Taliban first ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, they enforced a strict interpretation of law, imposing harsh restrictions, especially on women and minorities. However, even during that period, the legal abolition of slavery remained in place–there were no reports of the Taliban formally recognizing or reviving chattel slavery as an institution.

The 1996–2001 Taliban regime had no written constitution or comprehensive legal code; they ruled by decrees and Islamic courts. While gross human rights abuses occurred (including forced marriages and bonded labor in some cases), the Taliban did not explicitly codify a return to slavery. Afghanistan at that time was still officially bound by its prior international commitments and the 1990s Taliban did not announce any policy to contradict the anti-slavery norm. In essence, the abolition that began in the 1920s survived through the tumultuous decades of coups, communist rule, civil war, and even the first Taliban government.

Following the U.S.-led intervention and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2004–2021), the country’s laws continued to outlaw slavery, in line with the 2004 Constitution which guaranteed fundamental rights and upheld all prior human rights treaties. Slavery was simply a non-issue in Afghan law–until the return of the Taliban to power in August 2021. Over 2022–2025, Taliban authorities ruled largely via edicts from religious leaders. Then, in January 2026, the Taliban introduced a new “Criminal Code of the Courts”, a document that, for the first time under their rule, attempted to codify a wide range of offenses and penalties. It is in this 119-article code that the Taliban notably reintroduced classical terminology distinguishing free persons from slaves.

The Taliban’s 2026 code does not overtly legalize the capture or sale of slaves, but by using the word “slave” (ghulam or bardah in legal context), it implies that the status of slavery is legally recognized should it occur. Several provisions in the code raised an alarm. As mentioned, Article 15 treats “slave” as a possible status of an offender, and other clauses refer to a “master” in ways that suggest the law envisions scenarios of ownership. This effectively rolls back a century of Afghan legal precedent.

Afghan legal experts quickly pointed out that such language conflicts with Afghanistan’s binding obligations under international law, which absolutely prohibit slavery as a jus cogens norm (a peremptory, non-derogable principle). The human rights organization Rawadari warned that by describing individuals as “free” and “slave” in a law, the Taliban have given official legitimacy to a concept universally outlawed for its violation of equality and human dignity. Indeed, slavery is one of the few practices considered so abhorrent that it is banned at all times, even during war, by global agreements.

From an Islamic standpoint, the Taliban’s throwback to medieval legal terminology has been met with disapproval by many Muslim scholars. While the Taliban justify their laws as strictly adhering to early Islamic texts and fiqh, critics note that virtually all Muslim nations today have abandoned slavery and that nothing in core Islamic teachings compels its return.

Modern Islamic jurisprudence bodies argue that slavery was tolerated in early Islam as a transitional phenomenon and that its abolition in today’s context is not only permissible but laudable. The Taliban’s move, therefore, is seen as an ultra-conservative interpretation–one that ignores Islam’s overarching emphasis on justice and the maqasid (higher objectives) of Shariah, like freedom and human dignity.

As a former Kabul University law professor observed, Taliban jurists appear to be “transforming an abhorrent phenomenon into a legal concept” within their system, despite the fact that such concepts “have long since lost their meaning in Afghan society” and are despised worldwide, including by Islamic authorities.

International reaction to the Taliban’s implicit sanction of slavery has been sharp. Activists and foreign officials have described the new code as a flagrant breach of human rights, some even calling it a step back into “medieval” justice. For Afghan people, especially those from minority groups historically victimized by enslavement, the resurrection of the word “slave” in law is chilling. It conjures memories of past atrocities and raises fears about the erosion of rights under Taliban rule. Thus far, there have been no verified cases of the Taliban openly enslaving individuals in the manner of militant groups like Daesh (which infamously enslaved captives in the mid-2010s). Nonetheless, the legal door has been opened, at least on paper. The Taliban’s code, by categorizing people as slaves or free, sends a dangerous signal that unequal status by birth or capture is once again conceivable.

The legal history of slavery in Afghanistan reflects a broader tension between historical tradition and evolving standards of justice. For centuries, slavery was part of Afghan life, condoned under Islamic law, albeit with calls for humane treatment. In the 20th century, Afghanistan proudly joined the ranks of nations that abolished slavery, with leaders arguing that doing so fulfilled both Islamic and modern egalitarian ideals. That legacy held firm for over 100 years–a period during which Afghan society, like the rest of the Muslim world, came to regard slavery as a relic of the past, incompatible with contemporary interpretations of Islam’s message of human equality.

Today, under the Taliban, Afghanistan faces an uncertain crossroads. The reintroduction of slavery as a legal term under Taliban governance does not erase the fact that slavery remains illegal under international law and was repudiated by previous Afghan laws. The Taliban’s stance has positioned Afghanistan in opposition to global norms and the policies of all other Muslim-majority countries, which have long banned slavery. Many observers from within the Muslim world contend that the Taliban’s approach is a regressive anomaly–arguing that Islam’s true spirit is better reflected by the consensus against slavery, as exemplified by Afghanistan’s own 1923 abolition and its adherence to anti-slavery conventions.

In summary, Afghanistan’s journey with slavery has come full circle in legal terms: from outright abolition in the 1920s, through decades of compliance with Islamic and international norms, to a controversial revival of slave nomenclature in the 2020s. Whether this marks a temporary deviation or a lasting change will depend on Afghanistan’s future trajectory. According to experts, what is clear is that the ideal of a slavery-free Afghanistan, championed by King Amanullah and upheld by generations since, remains a powerful touchstone. It resonates with both modern human rights principles and the Quranic vision of human beings born free.