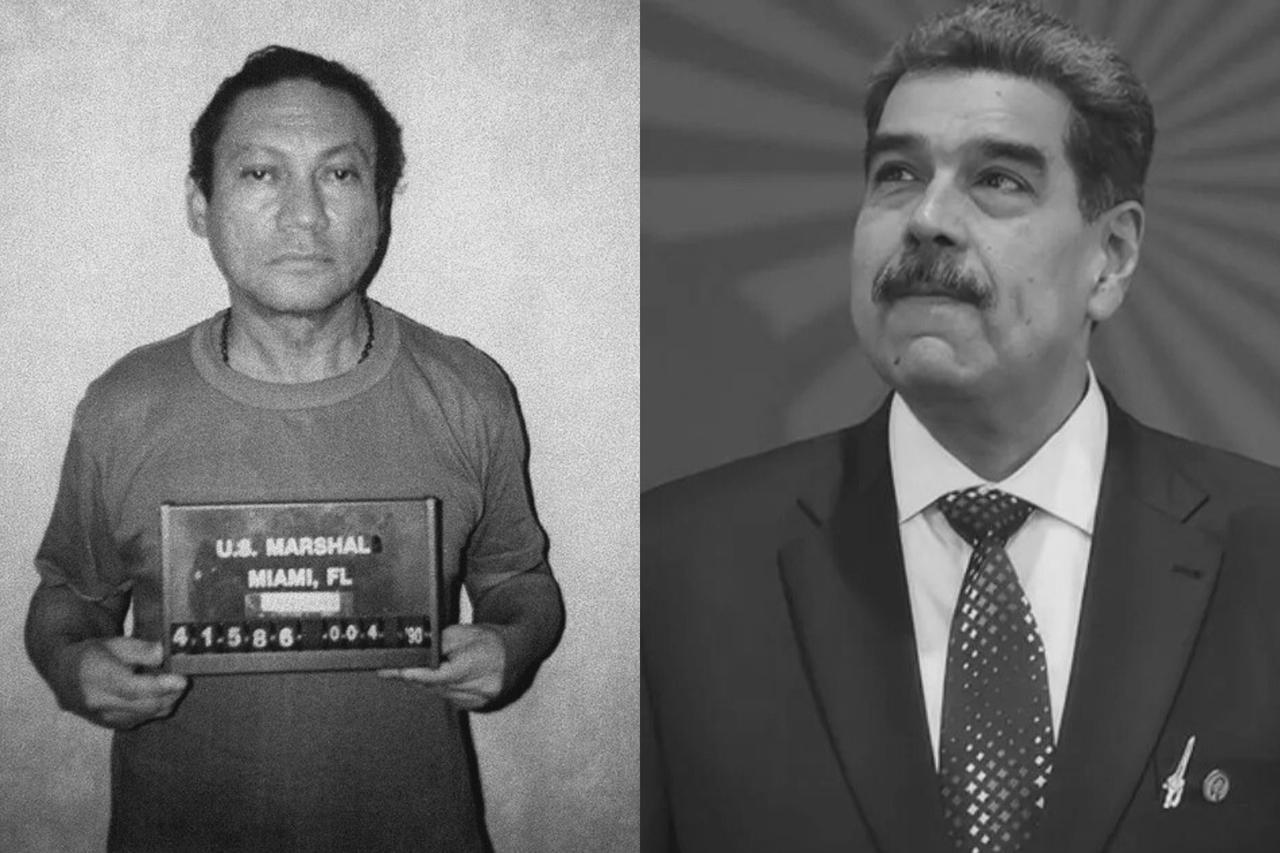

The United States has carried out what President Donald Trump described as a large-scale military strike against Venezuela, claiming that President Nicolas Maduro and his wife were captured and removed from the country, an assertion that, if confirmed, would mark the most direct U.S. military intervention in Latin America since the 1989 invasion of Panama.

According to Trump’s public statements, U.S. forces launched coordinated strikes on Venezuelan targets and subsequently detained Maduro, who has led the country since 2013, along with his wife, Cilia Flores.

Trump said the pair were taken out of Venezuela following the operation, framing the action as decisive and successful. The claim immediately drew global attention because of its scale and its implications for regional security.

This would represent a level of direct military involvement not seen in Latin America since the United States invaded Panama in December 1989 to depose Manuel Noriega, the country’s military ruler at the time.

That operation, known as Operation Just Cause, involved thousands of U.S. troops and led to Noriega’s capture and later prosecution in the United States.

Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez said in an interview with state television that the government is formally demanding proof that Maduro is alive. She stated that authorities in Caracas have no information about the president’s current location or physical condition, nor about the situation of his wife, Cilia Flores. Rodriguez underlined that the lack of verifiable information has left the government operating in a state of uncertainty.

Her remarks came after U.S. President Donald Trump said American forces had carried out large-scale strikes and captured Maduro. Rodriguez said the government has not been presented with any evidence to support those assertions, stressing that proof of life is now being sought as an urgent matter.

At the same time, independent verification of Maduro’s whereabouts has not been confirmed by neutral international observers, leaving a significant gap between U.S. claims and official statements from Caracas.

Analysts and diplomats have pointed out that the comparison with Panama is not merely symbolic. Since 1989, U.S. involvement in Latin America has largely been limited to sanctions, diplomatic pressure, security cooperation, and indirect military support, rather than overt strikes aimed at removing a sitting head of state.

According to experts, if Trump’s account proves accurate, the Venezuela operation would signal a sharp departure from decades of U.S. policy in the region.

Trump said additional details would be laid out during a press conference scheduled for 11 a.m. Eastern Time, which corresponds to 7:00 p.m. local time in Türkiye, with the address set to take place at Mar-a-Lago, his residence in Florida. The planned appearance from Miami has drawn attention because of its historical resonance, recalling the 1989 Panama intervention.

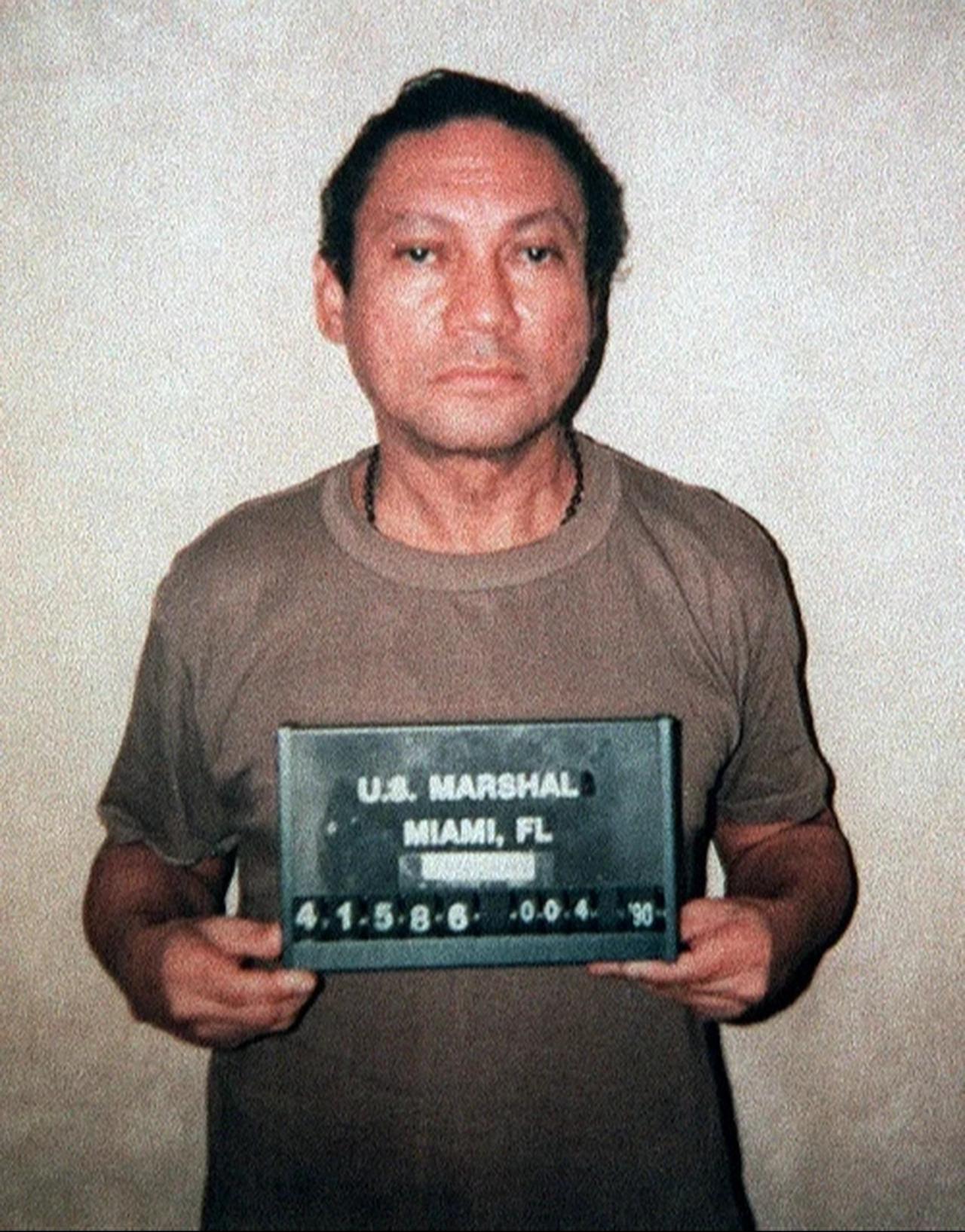

The beginning of Manuel Noriega’s downfall dates back to 1988, when U.S. federal grand juries in Miami and Tampa indicted him on drug trafficking charges, accusing him of helping Colombia’s Medellin cocaine cartel move large quantities of cocaine into the United States. Noriega initially responded with open defiance, dismissing US economic sanctions aimed at forcing him from power and publicly signaling that he would not step aside. In one widely noted episode, he waved a machete at a rally while vowing to remain in office, and in 1989 he annulled national elections that international observers said had been clearly won by the opposition.

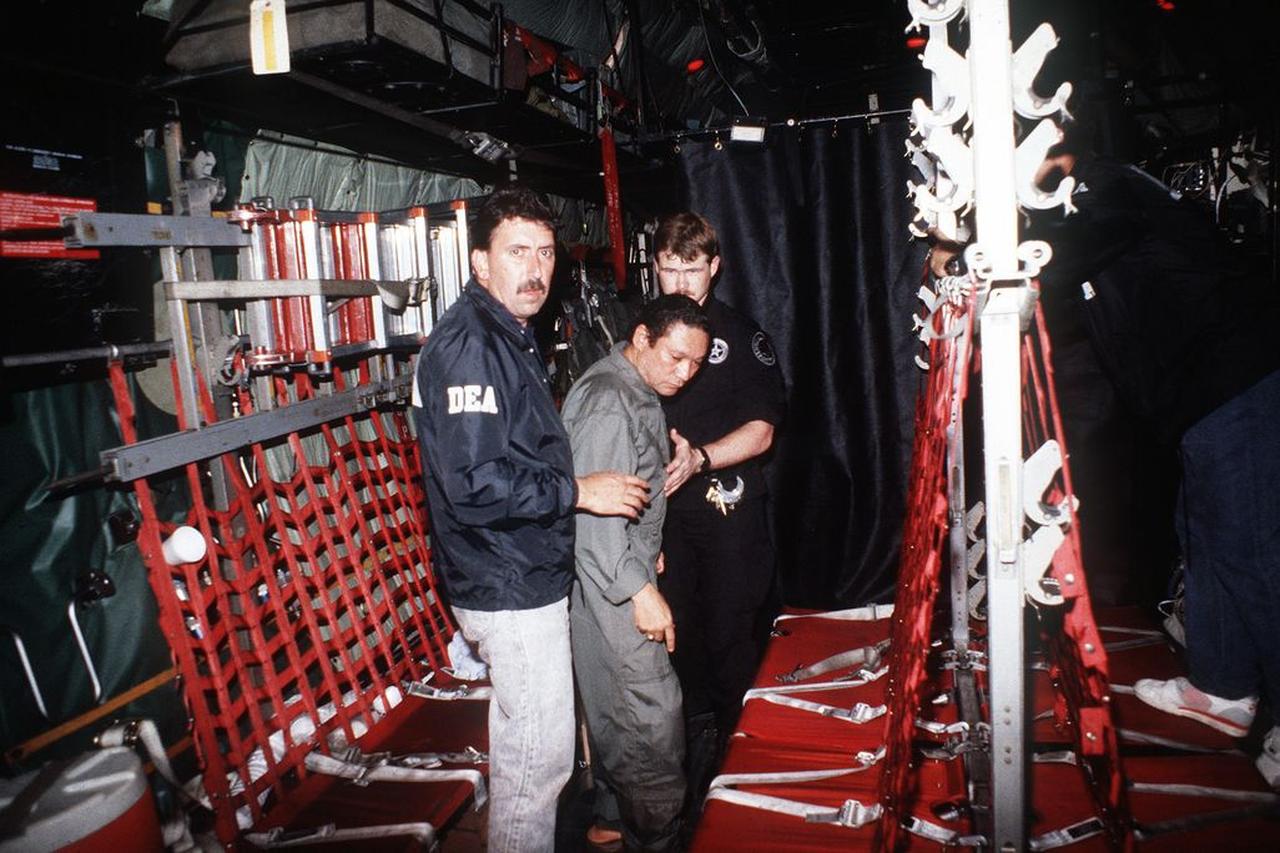

The standoff culminated in December 1989, when US President George H.W. Bush ordered a military invasion of Panama. Noriega was eventually captured and flown to Miami, a move that came to symbolize the most direct US intervention in Latin America in modern history. During the operation, 23 U.S. military personnel were killed and 320 wounded, while Pentagon estimates put Panamanian casualties at 200 civilians and 314 soldiers.

In court, prosecutors argued that Noriega had knowingly enabled large scale cocaine trafficking, while his defense pointed to documents describing him as a long time US intelligence asset, calling him the “CIA’s man in Panama” and claiming the indictment was politically motivated. In April 1992, a jury convicted Noriega on eight of ten charges, after being instructed not to weigh the political context of the invasion or whether Washington had the right to bring him to trial. During his incarceration at a minimum security federal prison near Miami, Noriega was granted prisoner of war status, including permission to wear his Panamanian military uniform during court appearances.

As current operations spanning December and January draw comparisons with the Panama case, the Noriega precedent continues to shape questions about whether similar legal and political outcomes could follow, even as the situation surrounding Venezuela remains unresolved.