For a brief moment in the late 2010s, the burgeoning alliance between Ankara and Caracas seemed to signal a new, defiant axis in global geopolitics. Defined by high-profile handshakes and a sudden surge in billion-dollar trade figures, the relationship was often framed by critics as a strategic defiance of sanctions pressure. However, beneath the performative solidarity of the post-2016 era, the foundations of this partnership remained remarkably thin.

As global dynamics shifted and the limitations of the Maduro administration became clearer, Ankara’s initial enthusiasm began to cool. Far from becoming a permanent pillar of Turkish foreign policy, the relationship has been steadily hollowed out.

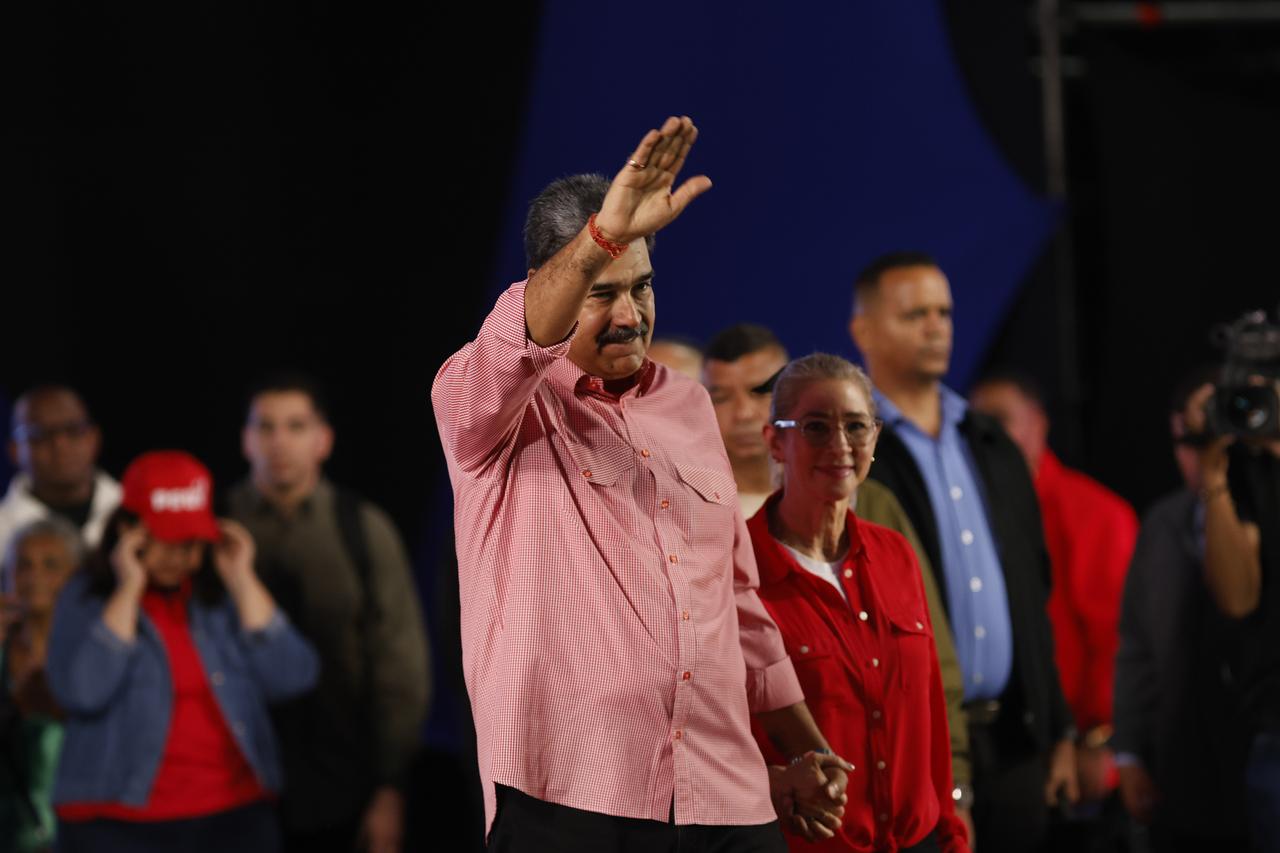

Between 2016 and 2018, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro met four times in quick succession. However, the momentum proved remarkably short-lived; in the eight years since that initial flurry, the leaders have shared only a single formal visit, in 2022.

In a recent diplomatic outreach last week, Erdogan contacted his Venezuelan counterpart to advocate for continued engagement with the United States.

A closer look at the trade data and diplomatic nuances reveals that Türkiye has not deepened its footprint in Venezuela; rather, it has spent the past several years executing a quiet, strategic retreat, prioritizing regional stability and Western balancing over a fragile and non-structural partnership.

Türkiye’s ties with Venezuela were limited and low-profile for years, lacking the institutional depth of a strategic partnership. The relationship gained visibility after the failed coup attempt in Türkiye in 2016, when Venezuela’s leadership was among the first to express political support for Ankara. This gesture was reciprocated diplomatically, leading to a period of intensified contact.

High-level visits followed, and bilateral trade briefly surpassed $1 billion, marking a historic peak in economic engagement. Yet this rise was neither institutionalized nor diversified across sectors. There were no enduring frameworks to stabilize or expand cooperation, making the relationship inherently fragile.

The volatility soon became apparent. Trade volume fell sharply to $152 million in 2019 and recovered only to around $300 million in 2020. In the past two years, including 2023, trade has failed to return to earlier highs, signaling a clear lack of momentum.

As of 2023, total trade between Türkiye and Venezuela stood at approximately $700 million. On its own, this figure reflects modest engagement rather than strategic alignment. A broader comparison further clarifies this point.

In the same year, U.S.–Venezuela trade reached around $6.5 billion. If commercial interaction were taken as an indicator of political closeness or ideological affinity, such figures would lead to misleading conclusions. The scale of U.S. trade alone demonstrates that limited economic exchange does not translate into political endorsement.

Türkiye’s export composition adds another layer of context. As the top export items, pasta, wheat flour, and soybean oil are all basic food products; the exports almost qualify as a humanitarian effort. These goods suggest routine commercial exchange and supply continuity, not a partnership rooted in strategic sectors or geopolitical coordination.

Türkiye’s political posture toward Venezuela has become noticeably more cautious over recent years.

Following Venezuela’s controversial 2024 elections, Ankara refrained from extending formal congratulations to President Maduro. Instead, the presidential statement focused on conveying goodwill toward the Venezuelan people.

This distinction matters diplomatically. While avoiding public confrontation, Türkiye also avoided legitimizing the electoral outcome. Meanwhile, President Erdogan urged Maduro to "keep the dialogue channels with Washington open."

Taken together with stagnant figures, this approach indicated a gradual pullback for the observers of the ties. The emphasis has shifted from visible political engagement to a restrained, low-profile relationship between the people of the two countries.

Some critics point to Turkish energy-sector activity in Venezuela as evidence of political support for the Caracas government. However, this claim does not hold up when viewed in a broader international context.

As it is known that the major U.S. energy firm Chevron remains active in Venezuela through joint operations with the state-owned PDVSA, operating under licenses issued by Washington. These activities are not interpreted as undermining international efforts to limit Maduro’s access to resources or prolong his rule.

By the same logic, Turkish energy investments cannot be taken as proof of political backing. They reflect narrowly defined commercial engagement rather than an attempt to shield or sustain the Venezuelan government.

Efforts to portray Türkiye as closely aligned with Venezuela are often reinforced by references to claims made by Sedat Peker, a figure of crime lord in exile. These allegations are frequently recycled in lobbying circles seeking to cast Ankara as acting against the interests of its Western allies.

Yet the most reliable data tell a different story. According to 2023 figures, countries such as Brazil, Panama, and Colombia maintain trade volumes with Venezuela comparable to Türkiye’s. Beyond the region, Spain, Italy, and even India have reached similar levels of economic interaction with Caracas.

In this comparative context, Türkiye’s engagement appears neither exceptional nor politically charged. The evidence instead points to a controlled, narrowing relationship, one defined by caution, selective economic ties, and a clear reluctance to deepen political alignment.