“I hear (Türkiye) and Iran are lovely this time of year,” wrote U.S. Sen. Lindsay Graham on the social media platform X in support of President Donald Trump’s increasingly tough posture against Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro. Graham, a South Carolina Republican who is an influential name in foreign policy matters as well as an ally of Trump, suggested that the Venezuelan leader should consider retiring to Türkiye.

Graham’s Nov. 29 post looked like something out of “America’s Most Wanted.” “For over a decade, Maduro has controlled a narcoterrorist state that is poisoning America, and he has created alliances with international terrorist organizations like Hezbollah,” in reference to the Shiite armed group and political party from Lebanon that Washington designates as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO).

Graham’s statement follows a Washington Post story on Nov. 25 discussing the various exile or retirement options for the Venezuelan leader. From the looks of it, the United States is seriously considering Türkiye for the next chapter in Maduro’s life.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration designated the Venezuela-based transnational criminal network “Tren de Aragua” (Aragua Train) as an FTO. Since September, the U.S. Navy has been attacking ships coming out of the South American country, allegedly belonging to the group. So far, 22 attacks against naval vessels for suspected narcotics trafficking into the United States have led to the death of 87 people, according to a Dec. 5 report on Time magazine.

The Trump administration is signaling its intention to further escalate if Maduro does not relent. Besides accusing Maduro of enabling the Aragua cartel, the US is also claiming that his Venezuelan counterpart leads the “Cartel of the Suns” at home, along with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), another designated FTO. Trump is also claiming that Maduro orchestrates illegal immigration to the United States.

The Venezuelan government has rejected the claims, calling on Russia, China, and Iran to bolster its defenses. Although Trump had a phone call with Maduro on Nov. 21, it seems not to have had a noticeable effect on the escalating crisis. On Nov. 29, Washington declared the closure of Venezuela’s airspace, forcing many international carriers, including Turkish Airlines, to cease service.

That is the context in which the talk of a “Turkish exile” for Maduro has emerged.

Several factors, however, complicate this picture. On the one hand, the Venezuelan leader wishes to stay in power and protect his allies and family from prosecution in the United States or a third country. He is probably reluctant to come to Türkiye so long as the U.S. is holding a $50 million bounty on his head and an arrest warrant!

But provided Maduro gets at least some of his wishes regarding an amnesty but decides not to stay in power, Türkiye might be the ideal retirement spot for him. Even then, there are a few risks for the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, with whom the Venezuelan leader enjoys good relations.

“Maduro does not want to step down,” a Turkish national security official told Türkiye Today on condition of anonymity. “In their phone call on Nov. 21, he negotiated with Trump, even offering concessions in the country’s oil industry and rare-earth minerals. He also wants to stay in power and wants a global amnesty for himself and his friends and family in exchange for cracking down on the drug cartels.”

The South American country is estimated to house the largest reserves of crude oil in the world, including Saudi Arabia. Many suspect that the Trump administration’s support for the Venezuelan opposition against Maduro is tied to that 'minor' detail.

Since coming to power in 2013 following Venezuela’s legendary but controversial leftist President Hugo Chavez, who ruled between 1998 and 2013, Maduro’s reign has been marked by electoral irregularities, severe economic crises—including shortages of such necessities as food, gas, and toilet paper—and human rights violations. Besides the U.S. arrest warrant and bounty, he is facing a case at the International Criminal Court, although the Hague-based body has not issued a warrant or conviction.

Maduro has several options before him. Caribbean neighbor and fellow socialist Cuba might be ideal—the Washington Post story said Havana sent a personal security detail to Maduro and his allies—the Cuban economy is doing hardly better than Venezuela’s. At any rate, Cuba does not enjoy good ties with the United States, which means Maduro might not be safe there.

Two other options, Russia and Iran, also have more minuses than pluses. While Moscow might be safest for the Venezuelan leader, Russian oligarchs will try to exert too much pressure on him to invest his “savings” in unsavory schemes that will benefit the hosts rather than the newly arrived guest.

“Maduro being in Moscow also reflects poorly on the Russians,” the Turkish official said. “If they continue housing former heads of state in luxury villas or apartment complexes, as they are now doing with Bashar al-Assad, it sends the unintended message that Moscow cannot truly protect its friends and serves only as a fallback option, he added in reference to the Syrian dictator who was toppled in Syria’s December 2024 revolution following nearly 14 years of civil war.

In the Washington Post story, Turkish American expert Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish research program at the Washington Institute for Near East policy, underlined how Iran’s political instability and restricted social scene might not be so alluring.

Thus, should Maduro get his amnesty and decide to leave Venezuela (two big “ifs"), Türkiye might be his best shot. But even that is not a “done deal.”

For one, although there is chemistry between Erdogan and Maduro, their relationship is not as close as observers might assume. For much of the 2010s, Caracas had criticized Ankara for its role in the toppling of Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi and supporting armed rebels in Syria. But the July 15, 2016, coup attempt in Türkiye by elements loyal to the U.S.-based Fethullah Gulen, ringleader of the Fetullah Terrorist Organization (FETO), and Venezuela’s support for Erdogan, changed things.

As both Ankara and Caracas’ ties with Washington frayed in the late 2010s, Turkish energy and mining companies found themselves making brisk business in the Latin American country. Meanwhile, Türkiye’s burgeoning precious metals markets found a steady supply of gold and silver from Venezuela, with news reports and market gossip estimating anywhere between 9 tons to 17 tons of Venezuelan Central Bank gold parked in Istanbul and Ankara.

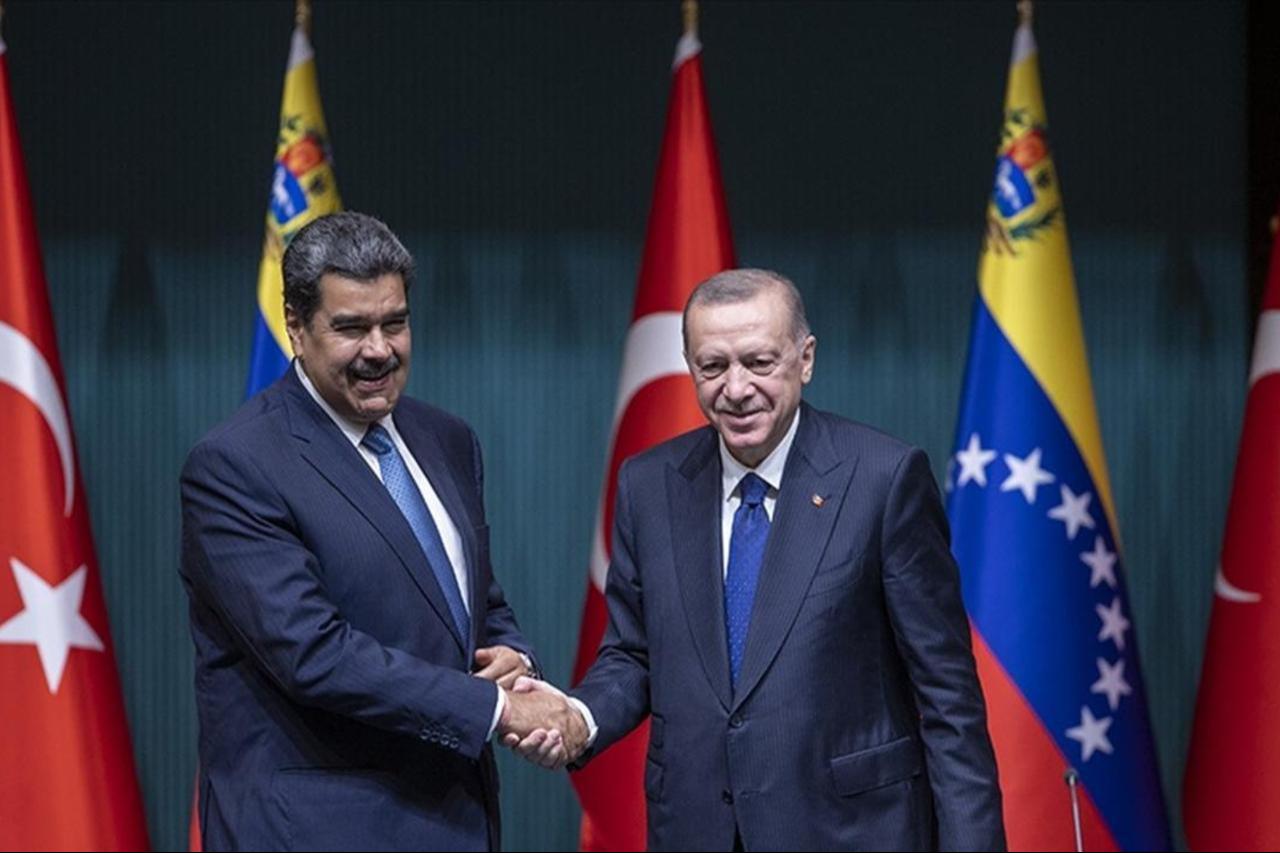

Money has followed political leaders. Erdogan and Maduro exchanged visits in recent years.

But that hardly means the two leaders are lockstep in everything. Following Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the West remembered that Türkiye is a NATO ally with a powerful military and robust defense industries, and that Ankara had been warning its Western partners about Russia’s intentions since the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014. It was a lack of NATO support for Ankara’s Syria policy (especially following Moscow’s direct intervention in that country’s civil war in 2015) and for Erdogan following the 2016 coup that made the Turkish president look for geopolitical alternatives.

With Trump’s second term and the chemistry between the Turkish and U.S. presidents, Ankara would not want to risk its ties to Washington for Maduro. A Turkish expert who spoke to Türkiye Today on condition of anonymity said, “Neither after Venezuela’s controversial election in 2024 nor during Erdogan’s phone call with Maduro afterward did the Turkish government explicitly recognize the election results.”

Similarly, Erdogan never really shared with Maduro the overtly anti-U.S. attitude that came out of the “bromance” in the late 2000s and early 2010s between then-President of Iran Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, Maduro’s predecessor. After nearly 23 years in power, the Turkish leader has become a master balancer of Türkiye’s independent foreign policy streak with its traditional ties to the West, especially the United States and Europe, as well as Ankara’s burgeoning new partnerships in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The “bromance” that matters here is the one between Erdogan and Trump, and the Turkish president would take steps that benefit him and Türkiye. Trump is likely to pledge a greater role for Turkish companies in Venezuela. Any any rate, Soner Cagaptay reminded the Washington Post, this would be “the fourth conflict that Erdogan is helping to end with Trump,” after Syria, Gaza and Ukraine.