The Turkish government geared up its efforts to tackle housing and rent inflation to reverse the decade-long decline in homeownership, alongside the newly introduced tradable real estate certificates, with a focus on supply and affordability through state-backed solutions.

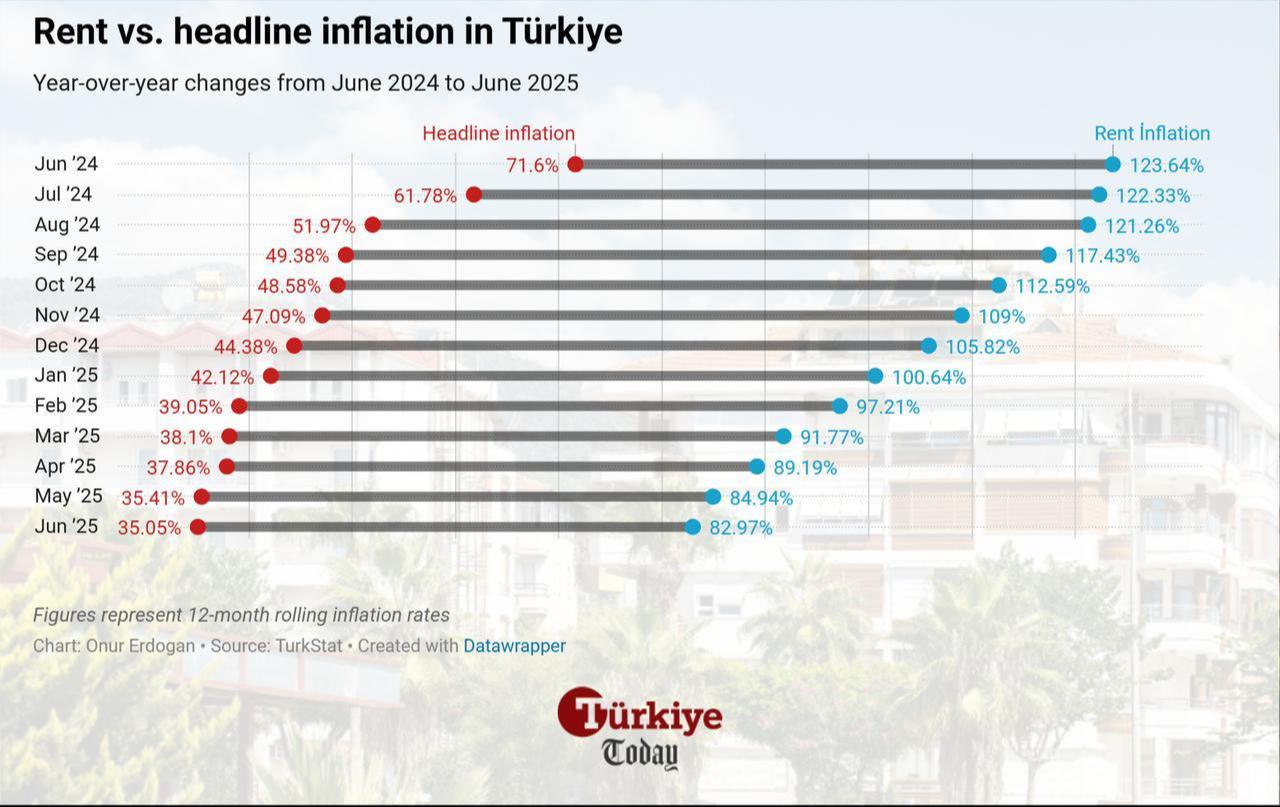

Amid unprecedented hikes in house prices and persistent rent inflation—which stood at 82.97% in June and has not eased for years—Türkiye far outpaced all OECD countries, with housing prices increasing nearly 21-fold and rents nearly 15-fold over the past decade.

While the state-run real estate developer Emlak Konut will launch the initial public offering of the first real estate certificates that will be listed on Borsa Istanbul between Aug. 4–8, additional moves are expected based on Treasury and Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek’s remarks addressing the issue.

Minister Simsek’s remarks stated that the government also prepares for 500,000 units of social housing and is adjusting mortgage maturities to 30–40–50 years, which currently stand at 10 years.

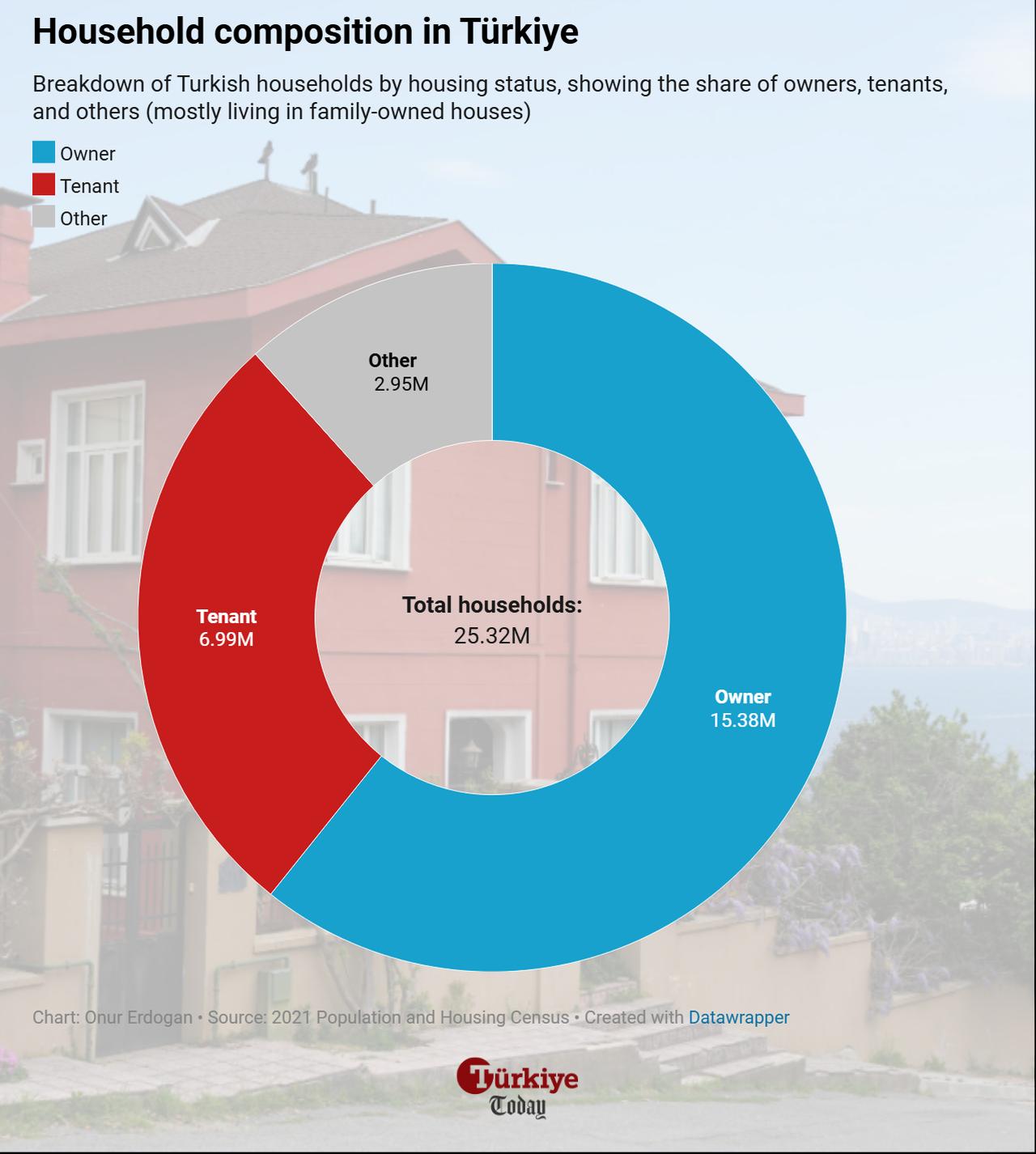

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute’s Poverty and Living Conditions Statistics in 2024, 56.1% of Turkish households are homeowners, while 28% pay rent and another 15% mostly live in family-owned houses.

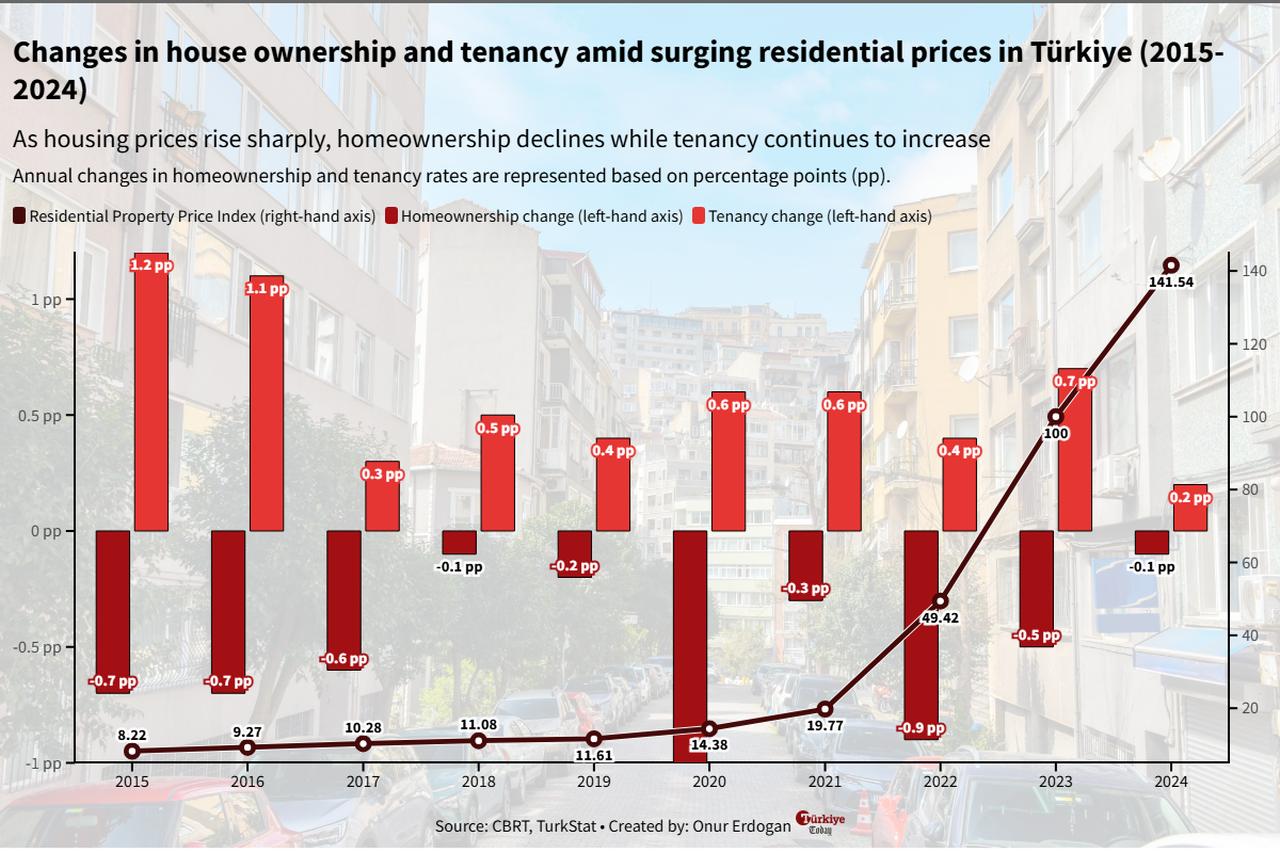

Taking a closer look, the data also show that the homeownership share among total households has been steadily declining each year over the decade, while the tenant share has risen.

During the period, homeownership dropped by 3.6 percentage points from 59.7%, while the tenant share rose by the same margin from 24.4% in 2016.

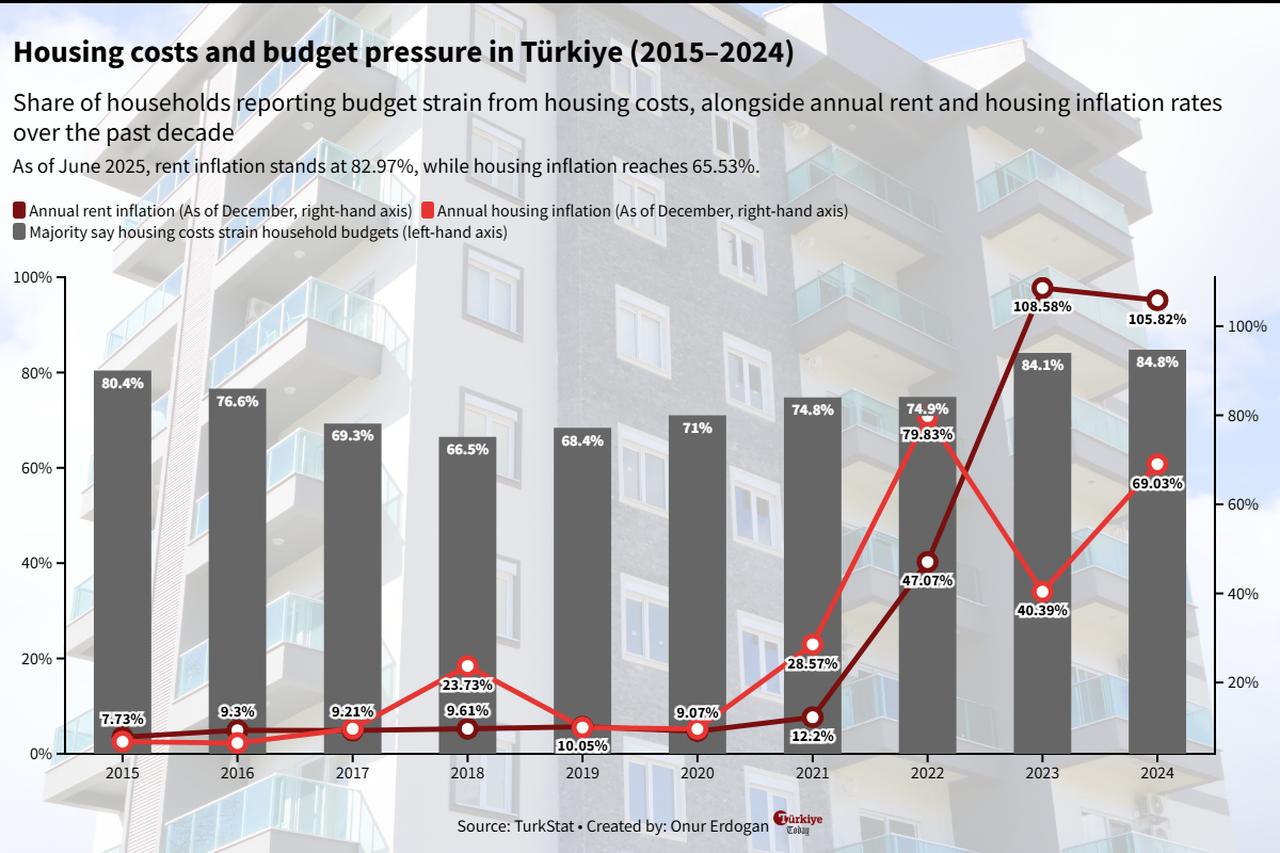

The situation also reflects the growing financial strain housing costs place on Turkish households, with a steady majority reporting budget pressure amid surging rent and housing inflation.

While more than two-thirds of households consistently stated that housing expenses strained their budgets, this share reached 84.8% in 2024, the highest in nearly a decade. Unlike many European countries, Türkiye does not provide subsidized rent support, further deepening the burden on tenants.

In numbers, among the total of 25.32 million Turkish households, 6.99 million pay rent, while 15.38 million live in their own houses, according to the latest data from the 2021 Population and Housing Census.

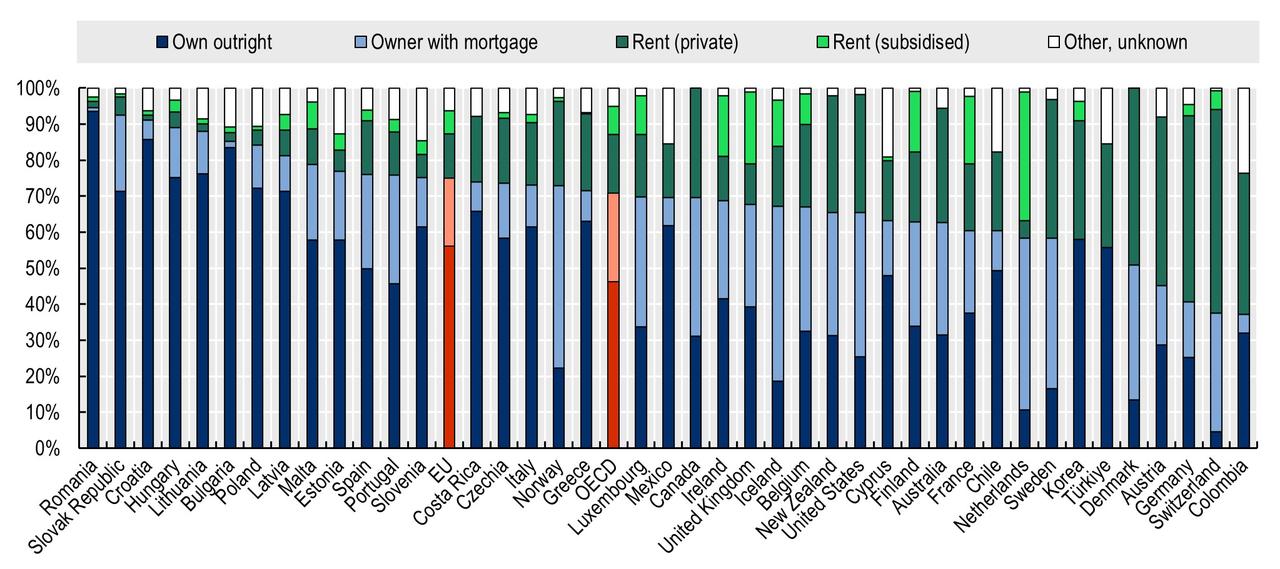

The OECD’s 2024 report shows that Türkiye also lags behind in homeownership, as the OECD average is 70.9% when mortgage-backed ownership is included. The share of tenants paying rent also surpasses the OECD average of 24%.

Meanwhile, according to calculations by business-focused dunya.com based on TurkStat data, approximately 8.5 million housing units remain unoccupied as of the end of 2024—likely due to seasonal use—adding pressure to housing supply, particularly in major cities, and driving prices higher.

The situation heavily affects the financial circumstances of Turkish households, as the average national rent stood at ₺23,402 ($589) as of June, with a 27.75% year-over-year increase, while it rose to ₺29,939 ($767) with a 38.39% year-over-year increase in the country’s largest city, Istanbul, according to AI-powered real estate price tracker platform Endeksa.

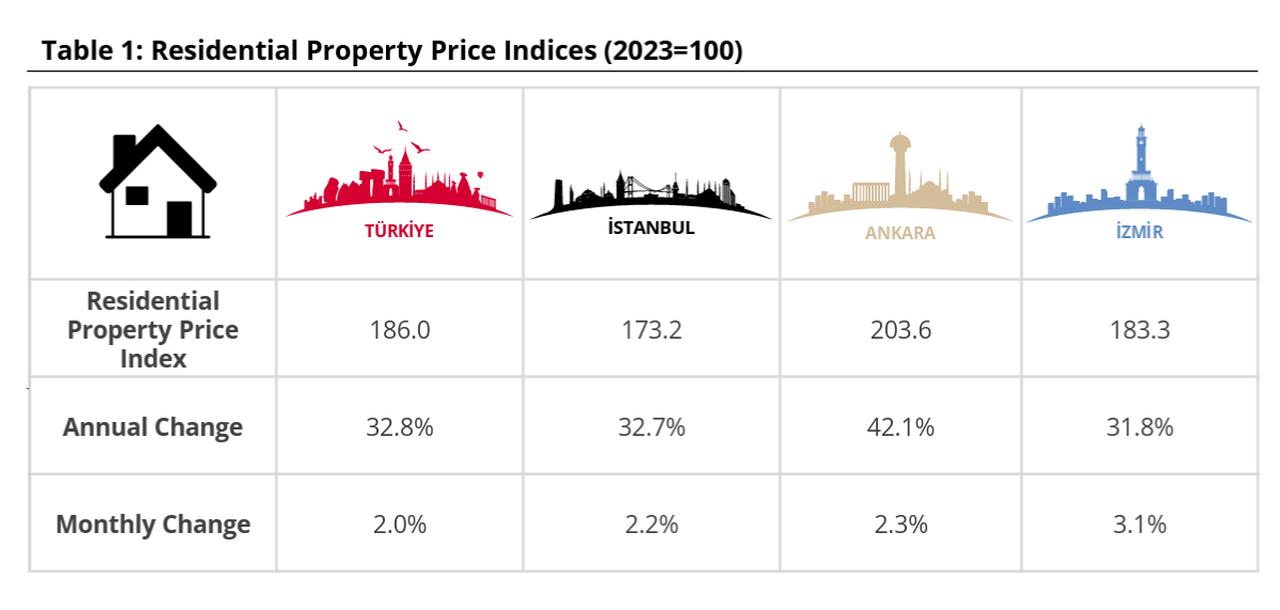

Central bank data show that Türkiye saw a 32.8% increase in house prices, while Istanbul remained slightly below this average at 32.7%.

Prices in the capital Ankara, which was once a cheaper alternative to Istanbul, rose by 42.1% year-over-year due to internal migration following the Feb. 6 earthquakes that killed over 60,000 people and destroyed 500,000 housing units.

Based on an optimistic estimation in a 2024 report by the Research Department of the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Türkiye (DISK-AR), as 53% of workers in the country earn a wage no more than 50% above the minimum wage —meaning their income does not exceed ₺33,156 ($817.76) per month, the prices remain too elevated for most households to afford.

Deepening the problem, high mortgage rates—averaging 42.56% annually—continue to hinder Turkish households from saving and turning their income into assets.

For an average national home priced at ₺4.36 million ($107,258), a 10-year mortgage at this rate results in a monthly payment of approximately ₺134,774.72 ($3,315). The situation is even more severe in Istanbul, where the monthly payment rises to ₺179,513.85, making mortgage financing increasingly inaccessible.

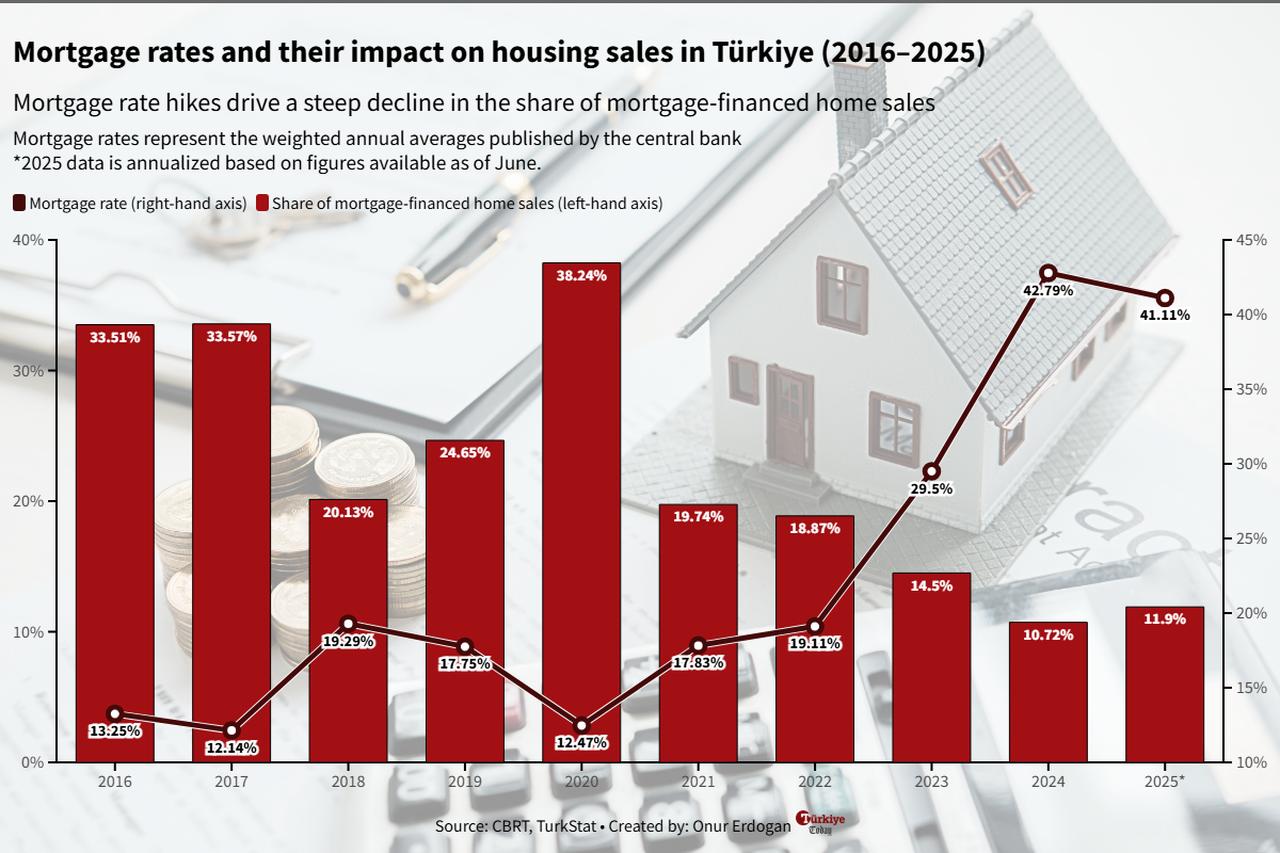

The growing unaffordability of mortgages is clearly reflected in market behavior: while the share of mortgage-financed housing transactions exceeded 30% in the early years of the last decade—peaking at 38.24% in 2020—it dropped sharply in subsequent years as borrowing costs surged.

Mortgage rates, which hovered between 12% and 19% for much of the decade, spiked from 19.11% in 2022 to 42.79% in 2024, before slightly easing to 41.11% in 2025. As a result, the mortgage share of housing sales fell to just 10.72% in 2024, followed by only a modest recovery to 11.9% in 2025.

On the other hand, rising housing prices and rents have also boosted the gains of investors who previously bought houses, as the amortization periods—the time it takes for an investment to pay for itself through rental income—have fallen to 14 years in Istanbul and 13 years for the Türkiye average.

As part of efforts to address the growing housing affordability crisis, the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change introduced a tradable real estate certificate program in July, allowing citizens to invest in residential projects through market-listed shares.

The program launched with the ₺51.1 billion ($1.25 billion) Damla Kent housing project in Istanbul’s Basaksehir district. Certificates are priced at ₺7.59 ($0.19) each and offer three options: accumulating shares toward full home ownership, receiving revenue from unsold units, or trading on Borsa Istanbul.

To fully own a 62-square-meter 1+1 apartment, investors need 631,516 certificates (₺4.79 million), while an 88-square-meter 2+1 unit requires 863,276 certificates (₺6.55 million). The model requires no down payment or mortgage, aiming to broaden housing access. Certificates will be available for a public offering from August 4 to 8 and begin trading on Aug. 11.

Despite its inclusive design, the program has faced criticism over unit prices. One-bedroom apartments in Damla Kent are priced at ₺77,311 ($1,905.97) per square meter, and two-bedroom units at ₺74,458—well above Istanbul’s 2025 average of ₺63,279 per square meter.

Prices in the project’s host district of Basaksehir are even lower, at ₺55,576 per square meter as of June, according to data from AI-powered real estate analytics platform Endeksa.

According to the Türkiye daily, Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek told ruling AK Party members during a closed-door meeting in July that 15% of Turkish households currently have no chance of homeownership under current conditions. He said the government plans to extend mortgage terms for low-income families from 10 years to 30–50 years.

Speaking in a live broadcast, Simsek emphasized that addressing affordability requires boosting housing supply rather than relying on cheap credit and noted coordination with the Urbanization Ministry to build at least 500,000 social housing units within 2–3 years.

The target of 500,000 social housing units accounts for approximately one-third of the total buildings constructed by the state-run real estate development agency TOKİ, which has built over 1.5 million housing units over the past 20 years as part of its social housing mandate.

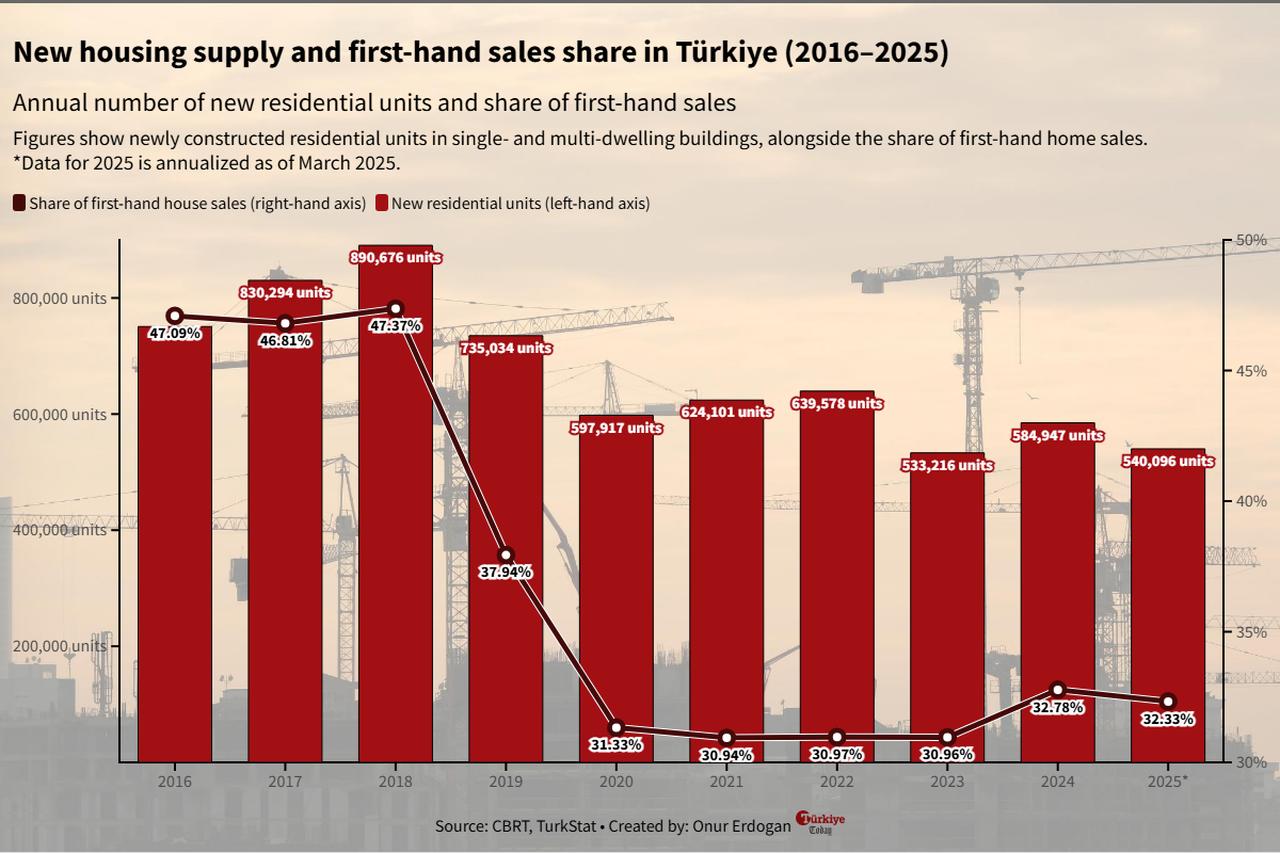

The number of social housing units Simsek indicated nears Türkiye’s annual newly constructed residential units figure, which stood at 540,096 as of March 2025 on an annual basis, showing a steady decline over the past decade.

First-hand sales also showed a continuous decline over the decade, dropping from 47.1% in 2016 to 32.3% in 2025, adding upward pressure to housing prices.

However, details of the proposed campaign have not been disclosed yet, as work continues.

Commenting on the developments, Nurbanu Turgen Zorlu, a real estate market expert at Istanbul Real Estate Valuation—a professional firm specializing in property appraisal and market analysis—says Türkiye’s newly introduced tradable real estate certificate program presents an innovative investment model.

However, she also emphasized that broader structural factors—such as long-term affordability, supply policies, and regulatory safeguards—must be addressed for the initiative to succeed.

Zorlu explained that the certificate model offers an accessible route for citizens to invest in large-scale housing projects by purchasing shares on Borsa Istanbul, without relying on mortgages, down payments, or long-term installment plans.

This flexibility, paired with state backing, allows individuals to either accumulate certificates for full ownership, trade for profit, or share in revenues from unsold units.

“These certificates can function like financial instruments. They offer an investment opportunity with built-in liquidity, and for many people, this may serve as a first step into the real estate market,” she said, highlighting the system’s accessibility and financial education potential.

Beyond financial innovation, broader government plans—such as extending mortgage maturities to 30–50 years and building 500,000 social housing units—serve as vital structural responses to Türkiye’s affordability crisis.

These moves, Zorlu said, are necessary given the country’s declining homeownership rates, rising rents, and mounting urban demand. In this context, she pointed to the government's planned 500,000-unit social housing project as a critical opportunity. “This will be especially meaningful for citizens who are looking to purchase their first home,” she underscored.

Zorlu explained that in developed countries, mortgage systems often run up to 30 years, but what makes them viable is not the duration alone. “The key factor is that monthly payments are in line with household income,” she added.

She noted that similar alignment in Türkiye could lead to a successful application of long-term mortgage systems and could help ease pressure on rental markets in the long term.

Zorlu stressed that the difficulty of owning a home is not unique to Türkiye. “Becoming a homeowner is getting harder not just in Türkiye, but across the world. And this trend is expected to continue,” she warned.

However, research conducted by the Centre for Economic Policy Research in 2024 also shows that Türkiye ranked worst in the world in housing affordability.

Commenting on whether state-backed policies would shorten amortization periods and deter investor interest, she said the outcome could vary depending on location and conditions.

She emphasized that policies on long-term mortgages and social housing should prioritize turning non-homeowners into homeowners.

“This system could also positively affect investor behavior,” she adds. “Instead of short-term profit-seeking, we may see a rise in long-term portfolio and rental income-focused strategies.”

Zorlu also commented on the potential to attract foreign capital to the Turkish housing market, which declined by over 10% in the first half of 2025 compared to the previous year.

“New policies can stimulate foreign investor interest—especially if supported by revisions to tax and citizenship regulations,” she said. “Making the secondary housing market and tourism properties more visible and attractive will be key.”

She concluded by emphasizing the need for strong financial governance to mitigate risks in state-backed initiatives.

“Risk management requires tight regulatory control. Urban planning and financial sustainability must go hand in hand to prevent supply-demand imbalances that could destabilize the market,” she suggested.