After remaining closed for 14 years following the fall of the Muammar Gaddafi regime, the Libyan National Museum has reopened in Tripoli, inviting visitors to step back into the country’s long and complex history.

Located inside the historic Al-Hamra Palace complex in Tripoli’s old city, the four-story museum now presents over 5,000 artifacts, arranged to guide visitors from prehistoric times through to the modern era.

The reopening, which took place on Dec. 12, marks a significant cultural moment for Libya, as the museum once again becomes a central space for preserving and displaying the country’s historical memory for both local audiences and international visitors.

Museum displays have been reorganized to take visitors through Libya’s history in a clear chronological flow, starting from prehistoric periods and continuing through ancient, medieval and modern eras.

According to Mohammed al-Shakshuki, head of Libya’s Department of Antiquities, the collection now reflects all major phases of Libyan history under one roof.

Roman-era sculptures form one of the most visually striking sections, while the Ottoman period is represented through a range of objects linked to governance and daily life. One of the most distinctive features is a reconstructed office of King Idris al-Senussi, Libya’s first monarch after independence, which offers visitors a glimpse into the country’s 20th-century political history.

Special attention has been given to the Ottoman era, particularly the period when Libya was ruled by the Karamanli family, an Ottoman dynasty that governed Tripoli and its surroundings.

Al-Shakshuki said the museum displays items associated with Yusuf Pasha Karamanli, including a portable throne and a bowl that were presented to him as gifts by the King of Spain.

Traditional garments representing the Karamanli family are also on display, helping to contextualize the political and cultural ties between North Africa and Europe during that period.

Another major section of the museum focuses on Libya’s resistance to Italian colonial rule in the early 20th century.

Personal belongings of Omar Mukhtar, widely known as the “Lion of the Desert” and a leading figure in the anti-colonial struggle, are among the most significant exhibits. These include his glasses, walking stick, rifle and selected written correspondence.

Al-Shakshuki noted that families of resistance fighters donated many of these items, ensuring that the memory of the anti-colonial struggle remains rooted in personal history.

The museum also displays belongings of other prominent figures, such as Suleiman al-Baruni, Ramadhan al-Suwayhli and Ahmed al-Sharif, including a sword attributed to the latter. A gallows used by Italian forces to execute 14 resistance fighters during the occupation period is also exhibited.

The museum’s reopening has also been shaped by efforts to recover artifacts smuggled out of Libya over decades of instability. Al-Shakshuki said that several items previously taken to countries such as Italy, France and Belgium have been returned.

In more recent years, 21 artifacts were recovered from countries including the United Kingdom, the United States, Austria, France and Switzerland through diplomatic efforts led by the Government of National Unity.

Among the notable recovered items is a mirror belonging to Yusuf Pasha Karamanli (Pasha of the Karamanli dynasty of Ottoman Tripolitania), which had been taken to the United States and has now been placed back on display.

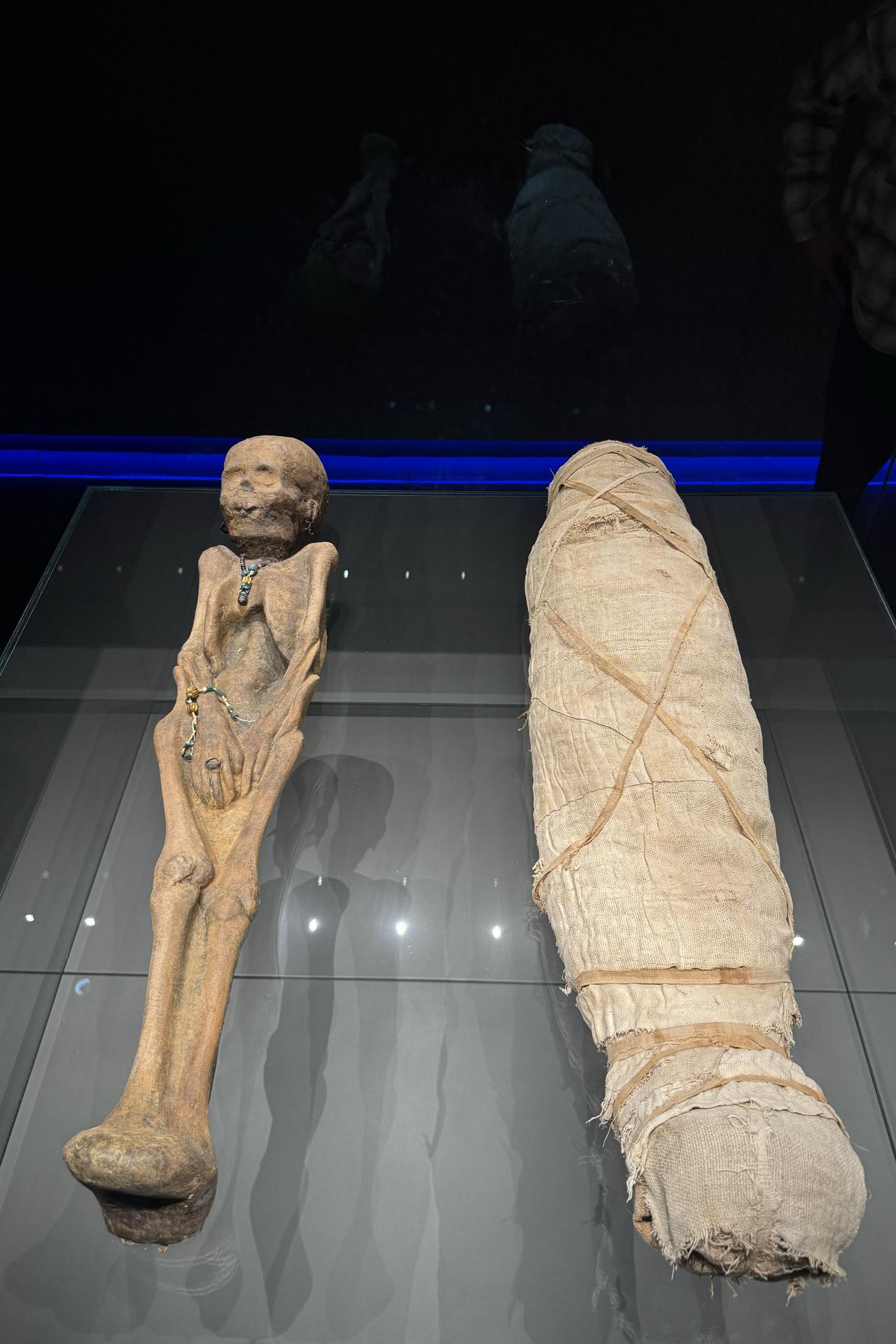

Museum director Kamal Youssef al-Shitwi added that the collection includes mummies dating back to periods earlier than the era of the Egyptian pharaohs. He described them as among the oldest known mummies, highlighting Libya’s often overlooked role in early human history.

Beyond political and military history, the museum also showcases traditional clothing representing Libya’s diverse ethnic communities.

Visitors have responded positively to these sections, with Tripoli resident Hanedi al-Qadi describing the renewed museum as impressive and appealing to a wide range of interests. She noted that the displays of traditional garments from across Libya draw particular attention, especially from women visitors.

Entry to the museum remains free until the end of the year. From the new year onward, ticket prices will be set at five Libyan dinars for children under 10, 10 dinars for adults, and between 15 and 20 dinars for foreign visitors, according to museum officials.