It would be naive to expect a global film festival to avoid political debate when cinema itself repeatedly confronts war, violence and death.

Yet this year's jury desperately sought to maintain an apolitical stance.

The 76th Berlin International Film Festival opened with a heated debate over the role of cinema in politics after jury president Wim Wenders said filmmakers should “stay out of politics,” triggering criticism from directors, writers and cultural figures worldwide.

The controversy emerged during the festival’s opening press conference, where the celebrated German filmmaker faced questions about the war in Gaza and the broader political responsibility of cinema.

His remarks quickly sparked backlash, including public criticism from Turkish director Emin Alper, a strong response from author Arundhati Roy, and a formal defense from festival organizers.

The debate has since expanded beyond the festival itself, raising broader questions about what “apolitical” art means and how such positions function within contemporary cultural and political conflicts.

The Berlin Film Festival began on Thursday under a politically charged atmosphere, with questions about global conflict and Germany’s support for Israel shaping the opening press conference.

When asked whether films can create political change, jury president Wim Wenders said cinema has transformative power but not in a political sense.

“Movies can change the world,” he said, but “not in a political way.” He added that no film has changed a politician’s views, though cinema can influence how people think about living their lives.

Wenders argued that filmmakers should not enter the political arena.

“We have to stay out of politics because if we make movies that are dedicatedly political, we enter the field of politics,” he said. “We are the counterweight of politics; we are the opposite of politics. We have to do the work of people, not the work of politicians.”

He also described a divide between individuals and governments, saying films operate within that gap by shaping personal values rather than political decisions.

The comments drew immediate criticism, particularly because they came amid ongoing debate over the war in Gaza and Germany’s political position.

Questions about the conflict dominated the press conference, with jury member and Polish producer Ewa Puszczynska describing such questioning as “a bit unfair” and saying filmmakers cannot be responsible for whether audiences support Israel or Palestine.

The press conference livestream experienced technical disruptions during these exchanges, prompting speculation about censorship. Festival organizers later attributed the interruption to technical problems and promised to release the full recording.

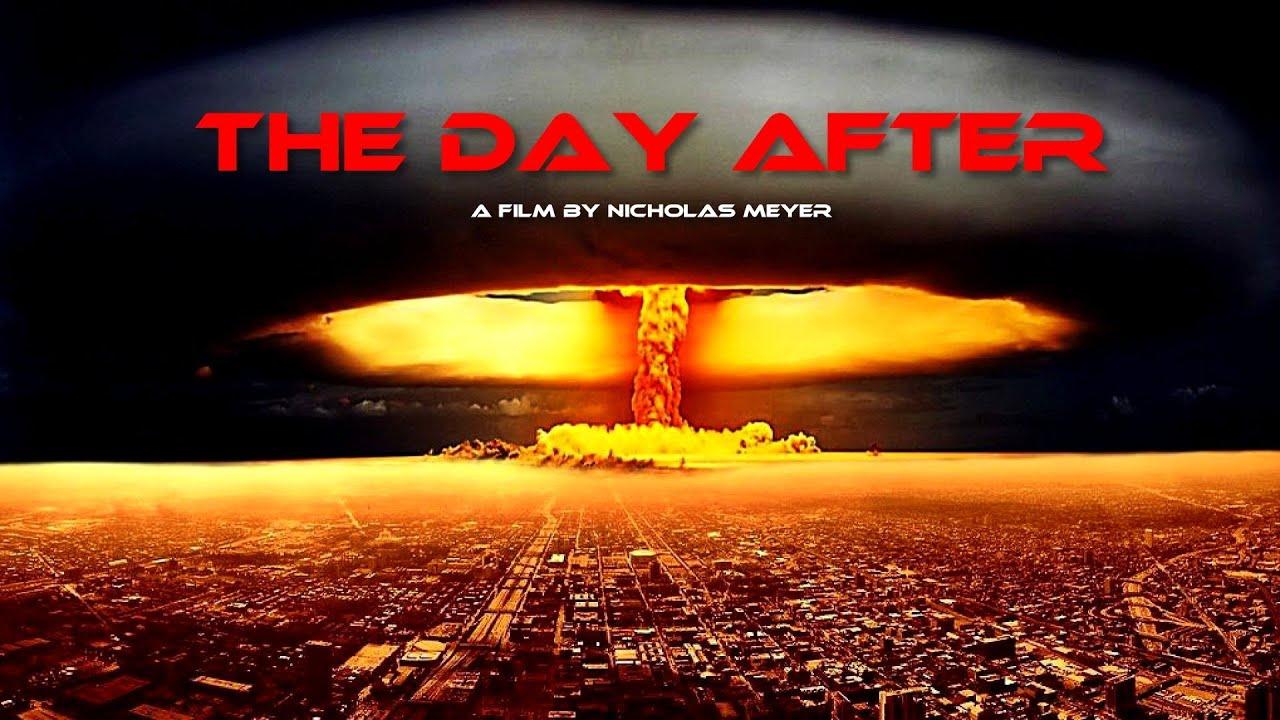

Historical evidence suggests that cinema has, at times, shaped political decision-making at the highest level.

The 1983 television film "The Day After", which depicted the devastating consequences of nuclear war, reached more than 100 million viewers in the United States.

As it turns out, it also profoundly influenced then-President Ronald Reagan’s understanding of nuclear conflict.

According to scholar David Craig’s research, the film offered a visceral portrayal of nuclear destruction that helped reinforce Reagan’s fears of global catastrophe, as reported by Outrider. It contributed to a shift in his approach toward the Soviet Union, encouraging a move toward diplomacy and de-escalation during the Cold War.

Reagan’s own diary entries, policy changes and subsequent efforts to reduce nuclear tensions have been cited as evidence of the film’s impact, illustrating how visual storytelling can shape not only public opinion but also the perspectives of political leaders.

Wim Wenders’ comments quickly triggered strong reactions from filmmakers and cultural figures.

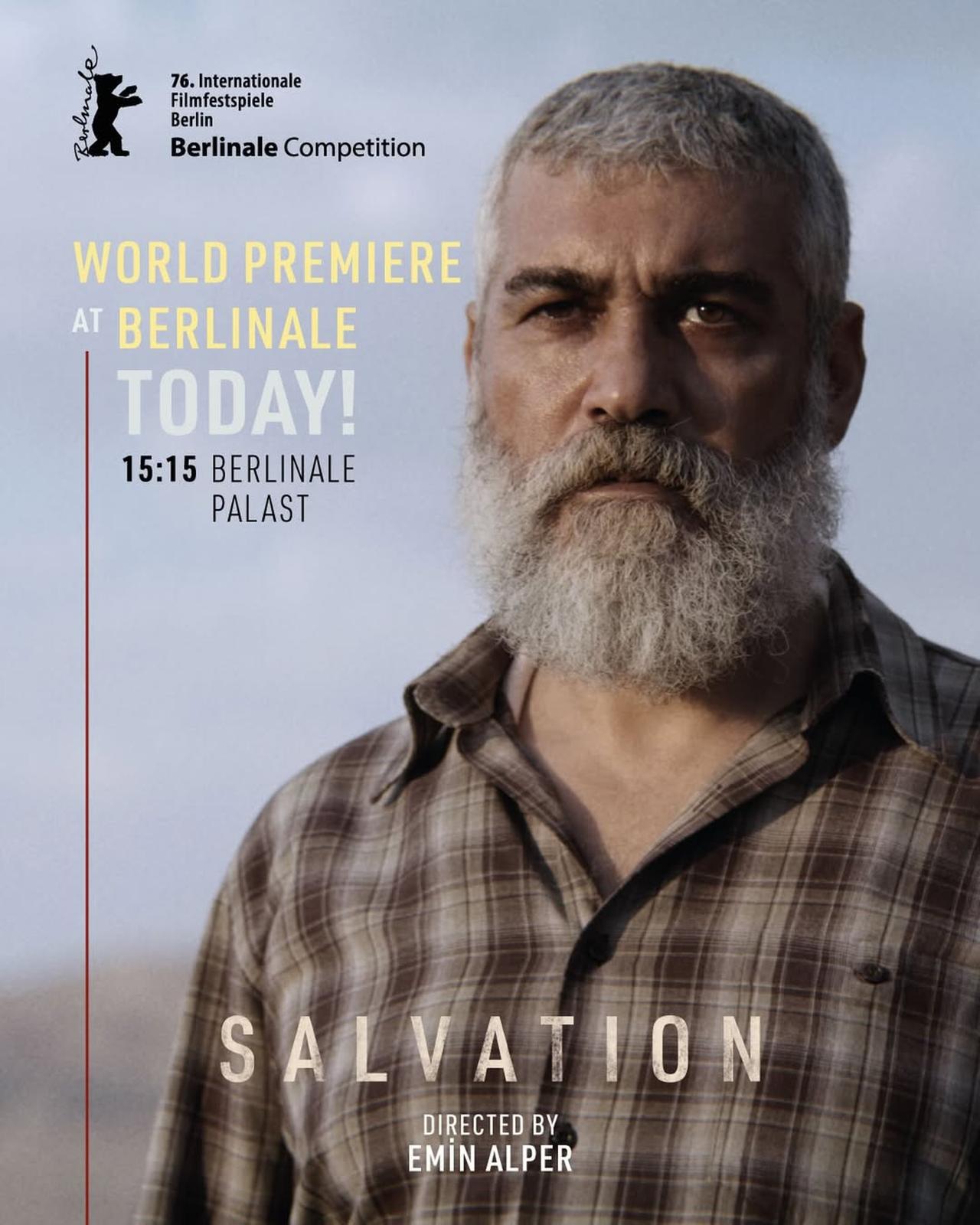

Turkish director Emin Alper, whose latest film “Kurtulus” (Salvation) premiered in the Berlinale main competition on Feb. 15 and is competing for the Golden Bear, publicly rejected Wenders’ position, arguing that separating art from politics is impossible.

“I cannot agree with Wenders’ words,” he said. “I have repeatedly said in various contexts that it is impossible to completely separate art and politics.”

He stressed that in many countries, politics directly shapes everyday life, making artistic neutrality unrealistic.

“In Palestine, Iran and many countries, including ours, politics is a matter of living and breathing,” Alper said. “It is therefore impossible to isolate art from life and thus from politics.”

Speaking at the world premiere of “Kurtulus,” Alper also linked the film’s themes to contemporary violence, describing it as a story about how communities can commit grave crimes. “Today, we are witnessing Israel’s genocide in Gaza,” he said, arguing that only a strong global reaction could stop such acts.

The film centers on a rural community drawn into a struggle over land and power, exploring how collective fear and the promise of “salvation” can lead to violence. According to accounts from the festival, Alper’s remarks received loud applause on stage.

The debate escalated further when Indian author Arundhati Roy withdrew from the festival in protest. She described the jury president’s comments as “unconscionable” and “jaw-dropping,” warning that they risk silencing discussion of ongoing violence.

“To hear them say that art should not be political is jaw-dropping,” Roy said. She argued that such statements “shut down a conversation about a crime against humanity even as it unfolds in real time,” adding that artists should use their influence to confront injustice.

The controversy also spread across social media, where critics accused Wenders of avoiding political responsibility and questioned the idea that artistic expression can exist outside power structures.

Festival organizers responded with a formal statement defending Wenders and the international jury, describing the backlash as a “media storm.”

Festival head Tricia Tuttle said artists should not be expected to comment on every political issue raised at press events.

“Artists are free to exercise their right of free speech in whatever way they choose,” she said, adding that they should not be required to address broader political debates unless they wish to do so.

A festival spokesperson also argued that public reactions had taken the jury’s remarks out of context and ignored the broader body of work and values of the artists involved.

In a separate statement titled "On Speaking, Cinema and Politics", Tuttle suggested the controversy reflected a wider media environment shaped by crisis coverage, where cultural discussions often become framed through political agendas.

She emphasized that art can engage politics in different ways and that filmmakers should not be pressured to compress complex views into brief responses during press events.

The controversy has developed into a broader cultural dispute about the meaning of artistic neutrality and the political role of cinema.

Supporters of Wenders frame his argument as a defense of artistic autonomy and freedom from political pressure. Critics, however, argue that describing art as “outside politics” can function as a refusal to address urgent social realities, particularly during periods of conflict.

Director Emin Alper’s response reflects a view common in societies where political conditions directly shape daily life, where artistic production becomes intertwined with questions of survival, identity and social struggle. Roy’s criticism similarly presents artistic silence as a political act in itself.

The dispute also reveals tensions within global cultural institutions, where festivals seek both artistic independence and public relevance while operating within specific historical and political contexts. It also raises questions about who organizes these events and the broader structures of power that shape them.

Many major cultural institutions are based in Western European societies that have historically exercised political, economic and cultural influence over non-Western regions, a legacy that continues to shape how global conflicts are framed and interpreted.

From this perspective, the ability to position art as “apolitical” may reflect institutional distance from the immediate consequences of war and political violence experienced elsewhere, allowing neutrality to function as a form of political positioning rather than the absence of it.

European traditions of neutrality further complicate this debate. Countries such as Switzerland have long cultivated international reputations for political impartiality while maintaining economic stability and influence during periods of global conflict.

Such models of neutrality raise broader questions about who benefits from claims of detachment and how cultural institutions negotiate responsibility in times of crisis.

Despite the debate, the 76th Berlin Film Festival continues its program, featuring films from around the world and running until Feb. 22. The jury, led by Wenders, includes filmmakers and industry figures from the United States, Japan, Poland, Nepal, South Korea and India.

Yet the controversy surrounding the festival’s opening days has already shaped its public reception, placing the relationship between art, politics and cultural responsibility at the center of global discussion.