In a quiet Istanbul street, just steps from the city’s busiest avenue called Istiklal, stands a museum dedicated to a fictional love affair.

Inside are cigarette butts, dresses, photographs, and everyday objects arranged in glass cases, preserving the traces of a relationship first imagined in the pages of a novel, “The Museum of Innocence.”

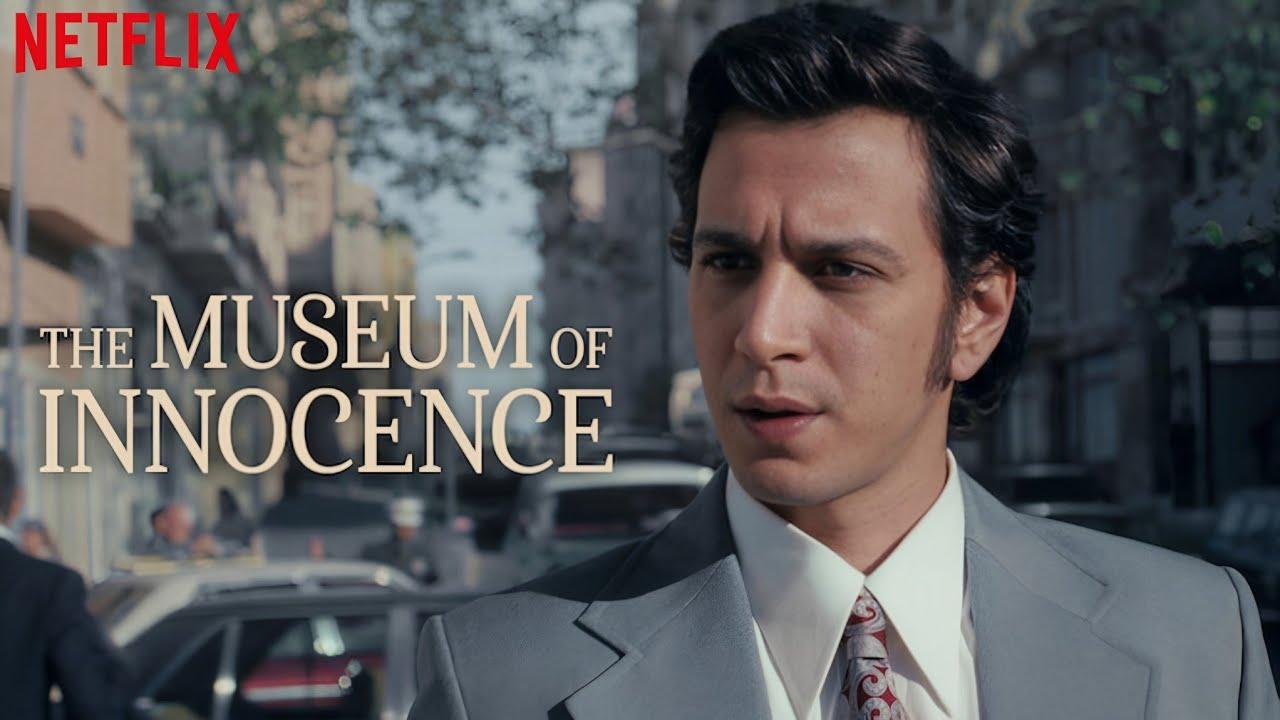

Now, Orhan Pamuk’s internationally acclaimed work has moved from page and physical space to the global screen, as Netflix released a limited series adaptation on Feb. 13, directed by Zeynep Gunay.

The project marks the first television series based on Pamuk’s 2008 novel but extends his long-standing fascination with transforming memory, narrative and everyday objects into lived cultural experience.

Orhan Pamuk, widely regarded as Türkiye’s most internationally recognized novelist, has published more than 20 books translated into over 60 languages, such as “The Black Book,” “My Name is Red,” and “Snow.”

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2006 and the Nobel committee praised him for having “discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures.” Literary figures such as Margaret Atwood have recognised Pamuk's ability to capture “the truth of human experience at a particular place, in a particular time,” a concern that also shapes “The Museum of Innocence.”

“It was the happiest moment of my life, but I didn’t realize it.”

The opening line of "The Museum of Innocence" sets the tone for a story shaped by memory, loss and retrospective longing. At the heart of the novel, lies a story of obsessive love.

Set in Istanbul in the 1970s, the novel follows Kemal, a wealthy businessman whose fixation on a young woman, Fusun, gradually evolves into a lifelong attempt to preserve the traces of their relationship. Rather than unfolding as a conventional romance, the narrative explores how love becomes entangled with possession, nostalgia and the passage of time.

What distinguishes the novel is its focus on objects. Everyday items such as 4213 cigarette butts, hairpins and clothing become emotional archives, carrying the weight of personal history. For Pamuk, these objects function as vessels of memory, turning private experience into something tangible.

The preoccupation with physical traces extends beyond fiction. Pamuk conceived the idea of both the novel and a corresponding museum in the mid-1990s, developing the two projects alongside each other.

The story does not simply describe a collection of objects but imagines a world in which memories are catalogued, displayed, and preserved. That impulse later took concrete form in the real Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, where the boundaries between narrative and reality deliberately blur.

Strikingly, Pamuk himself remains the only tangible presence behind this world of objects, carefully collecting and curating items that represent a fictional story in which he plays no role.

What began as a literary archive eventually took physical form.

In 2012, Pamuk opened the real Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, a space dedicated to objects described in the novel and designed to mirror its emotional universe. The project later expanded further with a museum manifesto, catalogue and a related documentary, "The Innocence of Memories" (2015), exploring the relationship between fiction and exhibition.

Located in Istanbul’s Cukurcuma district, a historic neighborhood in the broader Beyoglu area on the European side of the city, the museum presents carefully arranged displays, transforming narrative into spatial experience.

Moving through its rooms feels less like visiting an exhibition than entering a private home. The intimate arrangement of personal belongings creates the uncanny sensation of peering into a life previously encountered only in fiction.

Interest in the space has grown in recent weeks, with visitor numbers rising as renewed global attention turns to Pamuk’s work and its screen adaptation. Visitors encounter objects that exist simultaneously as narrative devices and physical artifacts, inviting them to experience the story through material traces rather than text alone.

The transition from novel to museum now continues with its move to the screen. The recently released Netflix series represents the latest stage in Pamuk’s effort to translate memory and storytelling across different forms, from literature to physical space and now to global digital audiences.

Bringing “The Museum of Innocence” to the screen was not straightforward. Orhan Pamuk had long hoped to see the novel adapted, but earlier attempts left him deeply uneasy.

After signing a contract with a Hollywood production company in 2019, he was alarmed by proposed changes that he felt fundamentally altered his narrative. “Too much change,” he later said. “Once you do that, the rest of the book is not my book at all.”

He later recalled the period as deeply distressing, telling The New York Times that he “had nightmares during that period, paying a lot of money by my standards to the California lawyer and worrying about, what if they shoot it the way they wrote it?”

The dispute led to a legal battle lasting more than two years, after which Pamuk reclaimed the rights to his work and partnered with the Turkish production company Ay Yapim, this time maintaining close creative control.

He also played a brief role in the show, appearing as himself in scenes where the fictional protagonist recounts his story.

The series took four years to complete, with the production team constructing an extensive set recreating Istanbul’s Nisantasi district of the 1970s. Pamuk reviewed scripts page by page, met repeatedly with the creative team and insisted that the adaptation remain faithful to both the novel and the museum that inspired it, requiring the story to be told in a single season.

The production also responded to earlier criticism of the novel’s male-centred perspective. Pamuk acknowledged these concerns, saying he accepts “all feminist criticism completely,” and supported the appointment of director Zeynep Gunay, whose approach introduced greater emphasis on the heroine’s viewpoint.

The adaptation becomes the latest stage in a project that has moved beyond literature into physical space and global media, continually reshaping the story it seeks to preserve.

It also raises a more unsettling question: if memory is constructed and curated, what distinguishes it from history, and which version of the past becomes accepted as real? The question now belongs not only to the novel, but to its viewers.