Ottoman miniature paintings carried a vivid record of empire, and it was built to be read as much as seen. Art historian Rana Demiriz says Ottoman miniatures hold a “colorful history,” because they let viewers witness key moments through the way central historical figures were staged and depicted at the time.

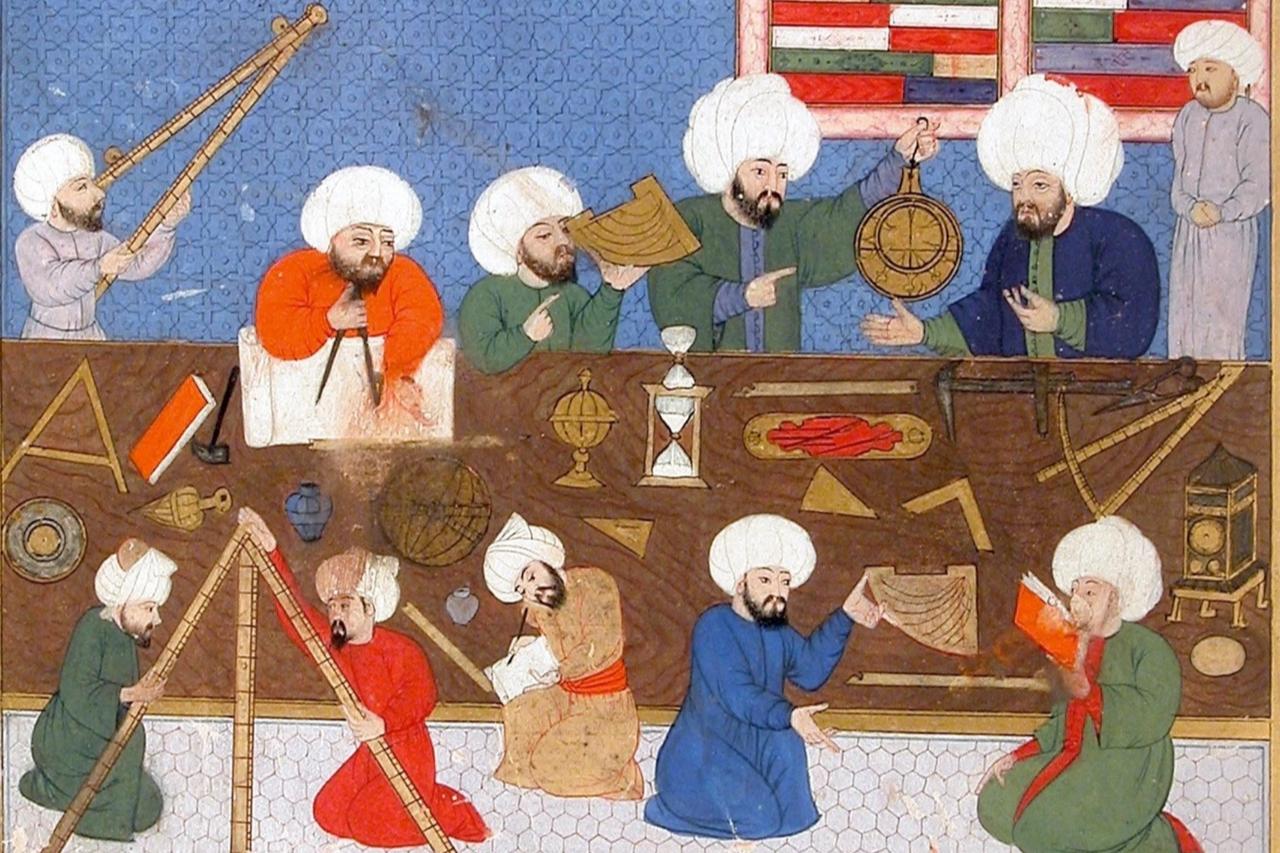

In the Ottoman world, abstract arts such as hat (calligraphy) and tezhip (manuscript illumination) reached a peak, while a highly visual art also sprang up between the pages of books. Miniature painting (Ottoman manuscript illustration) was, in effect, what painting came to be called in the Ottoman context. It followed its own rules and typically left out shadow and linear perspective, and its main center was the Saray Nakkashanesi (the palace painters workshop).

Rather than being made to be put up on walls, Ottoman miniatures were produced to back up texts and open up their meaning. Because of that, they could tell a great deal to anyone who knew how to read them, even though miniature painting was not widely embraced across all layers of Ottoman society. Over time, miniature painting gradually lost ground to canvas and wall painting.

Demiriz, who explores the subject in her Timas-published book Sanatla Yazilan Tarih (History Written Through Art), frames miniature painting as an art that developed alongside written works such as medical and historical books. She notes that figurative depiction in Ottoman decorative arts tended to be abstract, and in that setting, miniature painting emerged as a supporting element for texts.

She also points out that miniature painting in the Ottoman realm started out at a basic level in the era of Mehmed II, then took on a more established form from the 16th century onward. With artists brought in during Selim I, the range of practice widened, and under Suleyman I it fully took on a distinct identity.

Demiriz suggests that an “Ottoman school” can be discussed through leading masters associated with the palace, including Baba Nakkas, Nakkas Osman, and Levni.

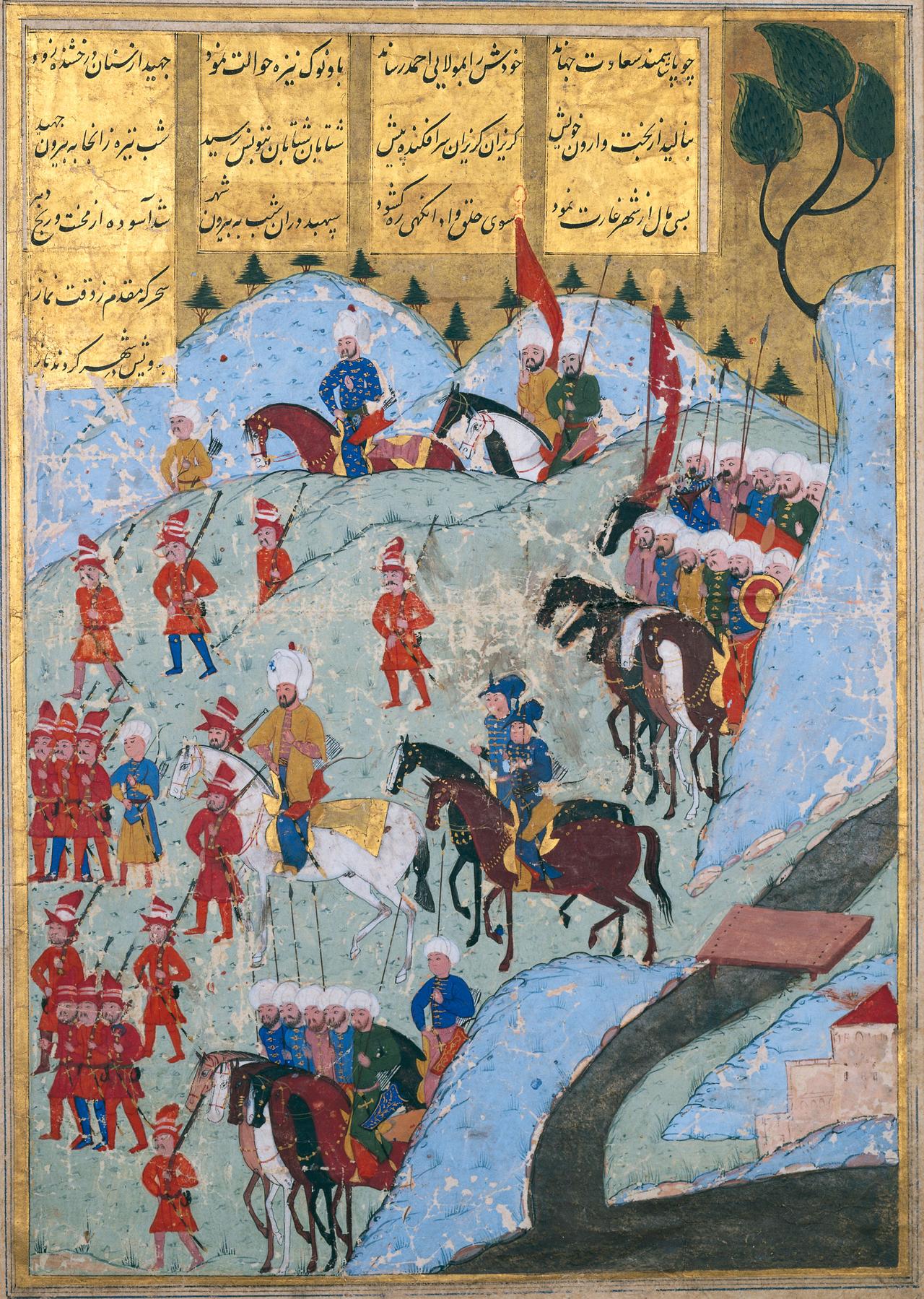

What set Ottoman miniatures apart, she says, was the way the sultan was staged. The ruler was typically drawn larger than everyone else so the viewer would spot him first, and distinctive colors such as red could be used to separate him from others. Sultans were also shown with standardized facial features, and she gives a specific example: Sultan Selim II was depicted with blond beard and blue eyes. A guidebook known as the Semailname (a work describing rulers physical traits) served as a reference for how sultans should be portrayed.

Demiriz describes miniature painting as an art that needs to be read. Even when the accompanying text is not visible, she argues that long-followed conventions can help viewers draw conclusions. If those conventions are not known, the images may seem meaningless, but once the rules are learned, the composition starts to give itself away.

Within that visual grammar, the most important figure is usually placed in the center or at the top. After identifying the main person, viewers can look at surrounding elements and begin to interpret what the scene is about.

In Demiriz's account, miniature painting was kept close to the palace largely because illustrated history books were being prepared there, especially during the reign of Suleyman I, when multi-volume histories were produced. As a result, victories, conquests, and military campaigns became the most frequent subjects.

At the same time, she notes that other themes also come up, including princes circumcision ceremonies, esnaf alaylari (guild processions), and depictions of buildings such as Hagia Sophia. In later centuries, portraits of sultans gained importance, as their images were meant to be handed down to future periods. In this sense, Demiriz keeps the key idea intact: Ottoman miniatures hold “a colorful history,” and above all, they let later viewers see the past through the way principal figures were presented.

Outside the court, Demiriz points to a group known as carsi ressamlari (bazaar painters), who from the 16th century onward produced miniature albums. These images could be shown in settings such as coffeehouses alongside oral storytelling. She says this environment also gave rise to humorous images, as well as unusual works such as illustrated dream-interpretation books.

She adds that after the discovery of the Americas, artists sometimes imagined unknown lands and beings and then produced miniatures based on those imagined worlds.

Demiriz argues that many manuscripts were preserved in good condition, including examples from the era of the Anatolian beyliks, because Ottoman sultans acted as committed collectors. Keeping works in the palace helped them make it through to the present day.

She also points to major collections and libraries such as the Yildiz Palace Library, Topkapi Palace, and the Suleymaniye Library as reasons the surviving body of manuscripts remains rich. While some works were taken abroad, she believes many manuscripts still remain unstudied.