Anatolia has long been described as one of humanity’s great laboratories — a land where the first farmers, early belief systems, complex states and empires emerged in close succession. In 2025, archaeological excavations across Türkiye once again confirmed this reputation, producing discoveries that not only filled gaps in historical records but actively challenged existing interpretations of ancient life.

From Neolithic sanctuaries that predate writing to underwater wrecks illuminating Ottoman-era trade and warfare, the year’s finds span nearly 12,000 years of human history. Some discoveries offered rare glimpses into belief systems and rituals, while others revealed the intimate details of daily life — what people ate, how they played, how they governed and how they buried their dead.

As the year comes to a close, this special roundup presents the ten most significant archaeological discoveries made in Türkiye in 2025, along with two bonus finds whose scale and interpretive importance proved impossible to overlook.

Together, they underline why Türkiye remains one of the world’s most critical regions for understanding the long and complex story of human civilization.

Here are the top 10 archaeological discoveries in Türkiye in 2025 — plus two extraordinary bonus finds that left a lasting mark on the year.

At the Neolithic site of Sayburc in southeastern Türkiye, archaeologists uncovered a striking stone sculpture depicting a human figure with what appears to be a sealed or stitched mouth. The unusual feature immediately drew attention, as it departs from previously known representations of the human body in early Anatolian art.

Researchers suggest the motif may symbolize silence, restraint, or a ritualized connection between speech and death. Rather than being associated with burial goods, the sculpture seems embedded in a broader ritual context, pointing to complex symbolic practices surrounding mortality long before the emergence of formal funerary architecture.

The find has sparked renewed debate about how early communities conceptualized death, the body and the afterlife — and whether such ideas were expressed through public ritual rather than private burial.

Karahantepe, one of the key sites within the Tas Tepeler cultural network, yielded one of the year’s most transformative discoveries: A T-shaped pillar bearing a clearly carved human face.

While T-pillars have long been interpreted as anthropomorphic, this is the first example where facial features are explicitly rendered. The discovery provides strong visual confirmation that these monumental stones likely represented human or ancestral beings rather than abstract symbols.

Dating back roughly 12,000 years, the pillar reinforces the idea that early Neolithic societies in Anatolia possessed a sophisticated visual language and shared symbolic system — one capable of expressing identity, authority and belief through monumental architecture.

Excavations at the Hisardere Necropolis in ancient Nicaea (modern-day Iznik) revealed a chamber tomb decorated with a fresco depicting Jesus as the Good Shepherd — a rare iconographic theme in Anatolia.

Dated to the third century A.D., the fresco reflects Roman artistic conventions while conveying early Christian theology centered on salvation and care. Scholars believe this may be the only known example of the Good Shepherd motif preserved in this funerary context within the region.

The discovery offers valuable insight into how early Christian communities in Anatolia expressed belief visually, blending classical artistic traditions with emerging Christian symbolism during a period of religious transition.

At Sefertepe, archaeologists uncovered two carved human faces on worked stone blocks alongside a small, dual-faced bead made of green serpentinite. Though modest in scale, the objects add an important layer to understanding symbolic expression in early Neolithic Anatolia.

The dual-faced bead, in particular, suggests themes of duality, transformation or protection — concepts widely attested in later belief systems. The finds demonstrate that symbolic creativity within the Tas Tepeler tradition was not uniform, but varied across sites and communities.

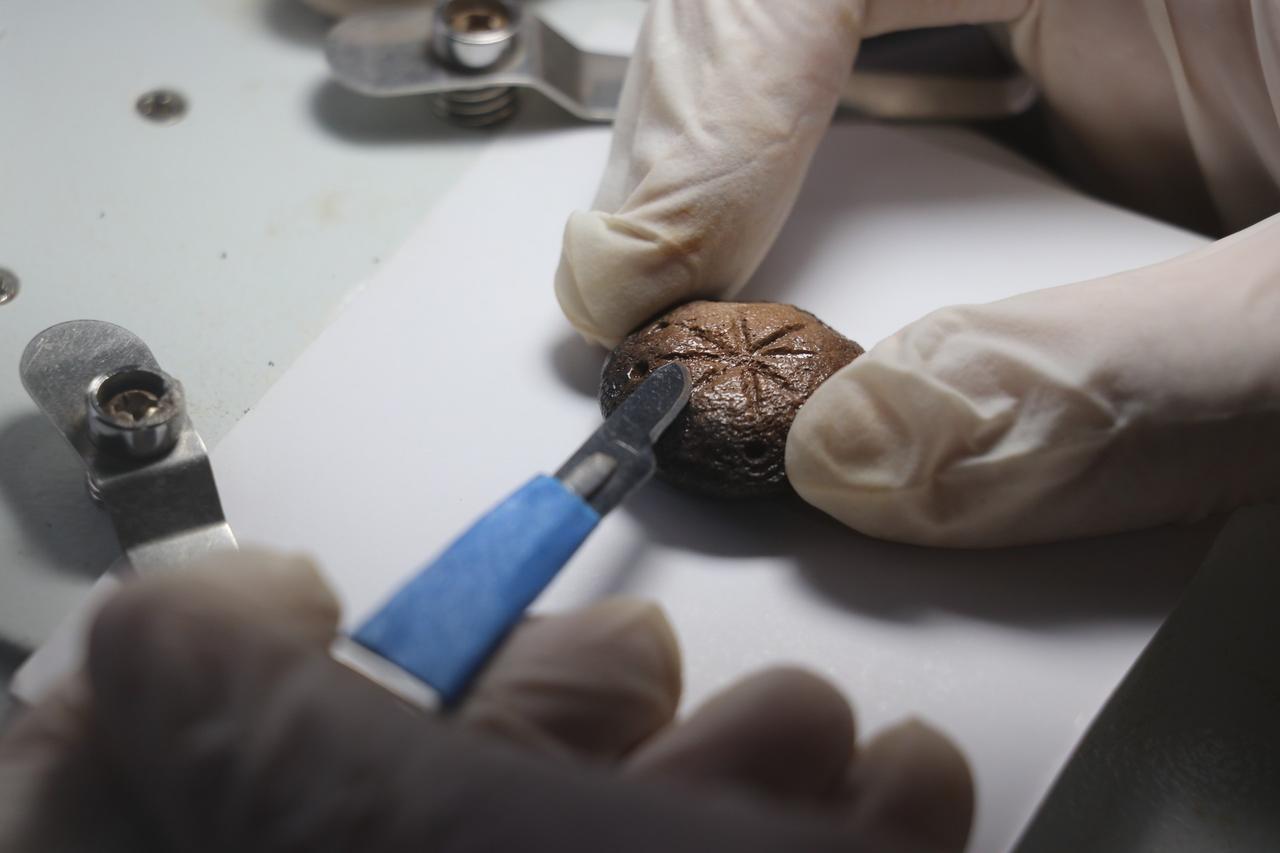

One of the most evocative discoveries of 2025 came from Kulluoba, where archaeologists uncovered a carbonized loaf of bread dating back nearly 5,000 years.

Laboratory analysis revealed that the bread was made using coarsely ground wheat mixed with lentils and processed through fermentation. Found at the threshold of a house and partially burned, the loaf may represent both everyday sustenance and ritual practice.

Beyond its symbolic value, the loaf offers direct, tangible evidence of Bronze Age culinary knowledge — transforming abstract discussions of ancient diets into something strikingly human.

Off the coast of Antalya, underwater archaeologists documented a ceramic cargo shipwreck dating to the late Hellenistic or early Roman period. The vessel carried hundreds of plates and bowls, carefully stacked and coated in raw clay to prevent damage during transport.

This innovative packaging technique highlights the sophistication of ancient maritime trade and suggests a standardized system for transporting fragile goods across long distances.

The wreck provides rare insight into commercial logistics in the Eastern Mediterranean and underscores the importance of Türkiye’s coastline in ancient trade networks.

Excavations at Hadrianopolis uncovered two bone gaming pieces bearing markings associated with Roman strategy games, possibly including Ludus Latrunculi.

The objects suggest that games played a role not only in leisure but also in training strategic thinking, particularly within military contexts. Their discovery adds a personal dimension to the lives of Roman soldiers and civilians, revealing moments of play within an otherwise rigid imperial structure.

At the early medieval site of Topraktepe in Karaman, archaeologists discovered five carbonized loaves of bread — one of which bears a stamped image interpreted as Jesus the Sower, accompanied by a Greek inscription.

The bread are believed to be connected to Christian liturgical practices, possibly used during religious ceremonies. Their preservation provides rare material evidence of how faith was embedded in everyday food production.

The Hittite site of Kayalipinar yielded a state archive of 56 cuneiform tablets and 22 seal impressions, many detailing bird divination rituals and administrative procedures.

The assemblage suggests the presence of a local bureaucratic center where religious practice and state governance intersected. The find significantly enriches our understanding of how ritual knowledge was recorded, transmitted and institutionalized during the late Bronze Age.

A comprehensive ancient DNA study conducted at Catalhoyuk revealed that households were organized primarily around maternal lineages.

The findings challenge long-held assumptions about patriarchal structures in early farming societies and suggest that women played a central role in maintaining social continuity.

A 17th-century Ottoman shipwreck off the coast of Mugla yielded an extraordinary cargo: firearms, grenades, Chinese porcelain and chess pieces.

The assemblage illustrates how military logistics and international trade coexisted within the Ottoman maritime world, offering rare underwater evidence of early modern globalization.

At Gobeklitepe, archaeologists uncovered a life-size human statue deliberately embedded into a wall — a placement interpreted as a ritual offering.

The discovery strengthens interpretations of Gobeklitepe as a dynamic ritual landscape where human representation, architecture and belief were deeply intertwined.