A clay tablet, known today as the “complaint tablet to Ea-Nasir,” written nearly 3,800 years ago has turned an otherwise obscure Bronze Age merchant into one of the most unlikely long-lasting figures of internet culture.

Ea-Nasir, a copper trader who lived in ancient Mesopotamia, is today widely known online as the subject of what is often described as the oldest surviving customer complaint, a status that pushed his name far beyond academic circles and into global meme culture.

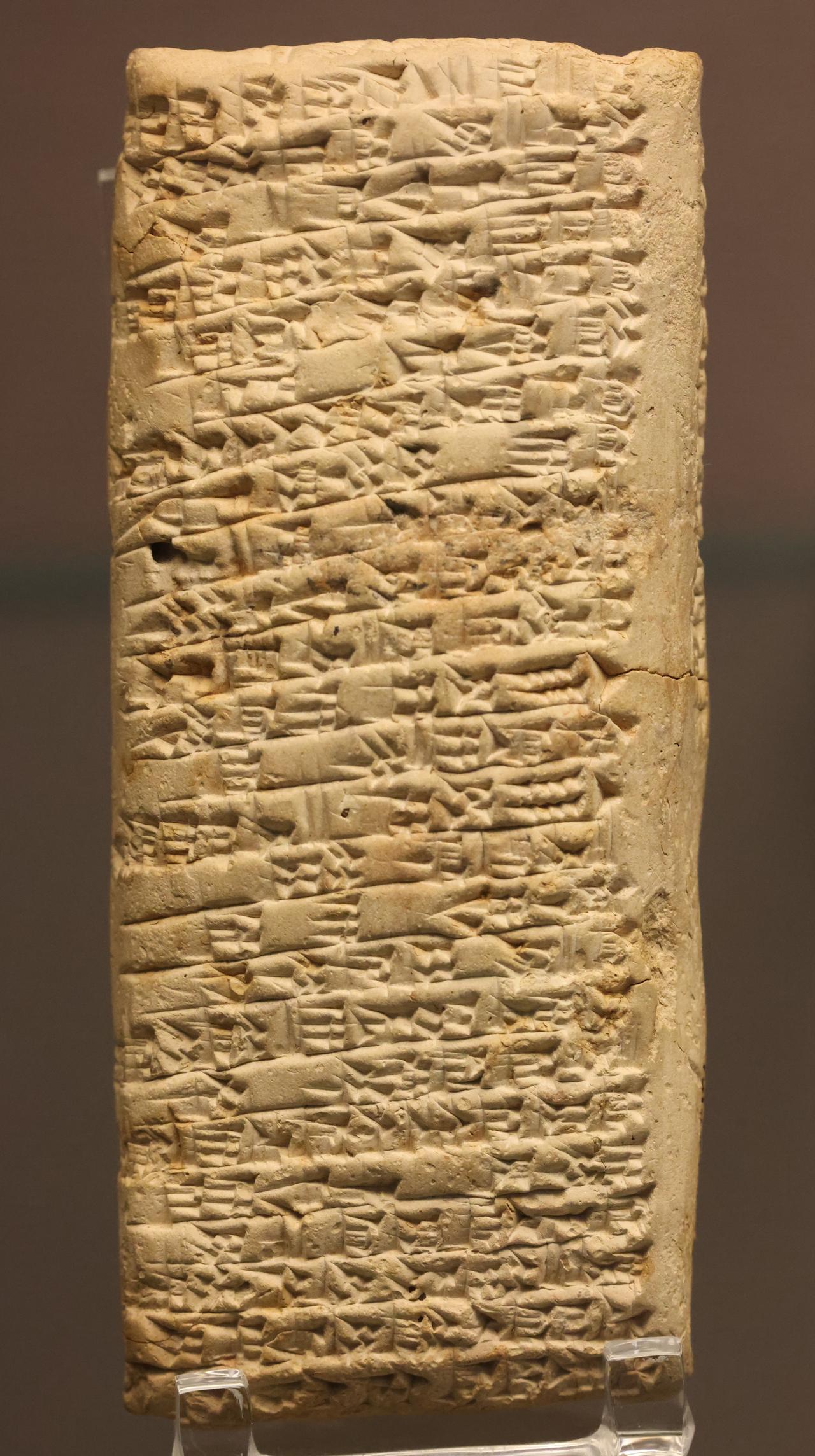

The tablet was discovered during the 1920s excavations at Ur, led by British archaeologist Leonard Woolley. Ur, located in what is now southern Iraq, was a major urban and economic center of ancient Mesopotamia. The tablet is currently displayed at the British Museum, where it is presented as part of the museum’s collection of cuneiform texts.

Written in cuneiform and dated to around 1,750 B.C., the tablet contains a sharply worded complaint addressed to a trader named Ea-Nasir. The author accuses him of supplying low-quality copper ingots and engaging in fraudulent business practices. Because of its tone and content, the text is widely referred to as the world’s oldest known customer complaint, offering a rare and vivid glimpse into everyday commercial conflicts of the Bronze Age.

Although known to specialists for decades, the tablet entered global popular culture much later. In 2015, images and translations of the text began circulating widely on platforms such as Reddit and Tumblr. These posts quickly attracted attention, leading to a wave of international media coverage that introduced Ea-Nasir and his copper trade to audiences far beyond archaeology and ancient history.

What followed was unusual in the fast-moving world of online trends. Rather than fading away, the complaint tablet became the foundation of a long-lasting internet meme. References to Ea-Nasir, his allegedly poor-quality copper, and the angry tone of the letter were repeatedly combined with images from popular culture, current affairs, and established meme formats, allowing the story to be continuously reinterpreted.

Academic analysis of this phenomenon has focused on how and why the meme endured. Gabriel Moshenska, a professor at University College London, has argued that the most plausible explanation is also the simplest. By examining a large collection of images, texts, and online commentary, researchers have traced the emergence and development of the Ea-Nasir meme within digital media. This work suggests that the meme functions mainly as an “in-joke,” shared and understood within particular online communities that enjoy blending obscure historical references with contemporary humor.

Within this process, Ea-Nasir himself has been reshaped into an archetypal “trickster” figure. Stripped of most historical detail, he appears online as a symbol of deceitful trade and dubious promises, a character type that easily fits into modern narratives about scams and failed transactions. This transformation helps explain the meme’s flexibility and its ability to connect ancient text with modern experiences.

While centered on a single artifact, this case study has broader implications. The analytical framework used to understand the Ea-Nasir meme offers a starting point for future research into internet memes as a form of digital folklore. It also provides tools for reception studies, showing how historical materials are reinterpreted by non-specialist audiences, and for related fields interested in how meaning is produced and shared online.

In this way, a complaint written nearly four millennia ago continues to generate new interpretations, proving that even the most ordinary documents of the ancient world can find unexpected afterlives in the digital era.