Archeologists working on material from the Boxgrove site in the U.K. have reported what they describe as the earliest known elephant-bone tool from Europe, saying a deliberately shaped fragment was used as a soft hammer to resharpen flint tools in an Acheulean (Lower Paleolithic) context dated to around 480,000 years ago.

Boxgrove, an extensively excavated open-air site along an ancient shoreline in what is now the southern part of the English Channel, has long been known for its rich record of stone tools and well-preserved fossils. Researchers say the newly analyzed elephant-bone implement adds to that picture by showing how organic materials could be worked up and then brought along for precise stone-tool maintenance at activity areas such as butchery spots.

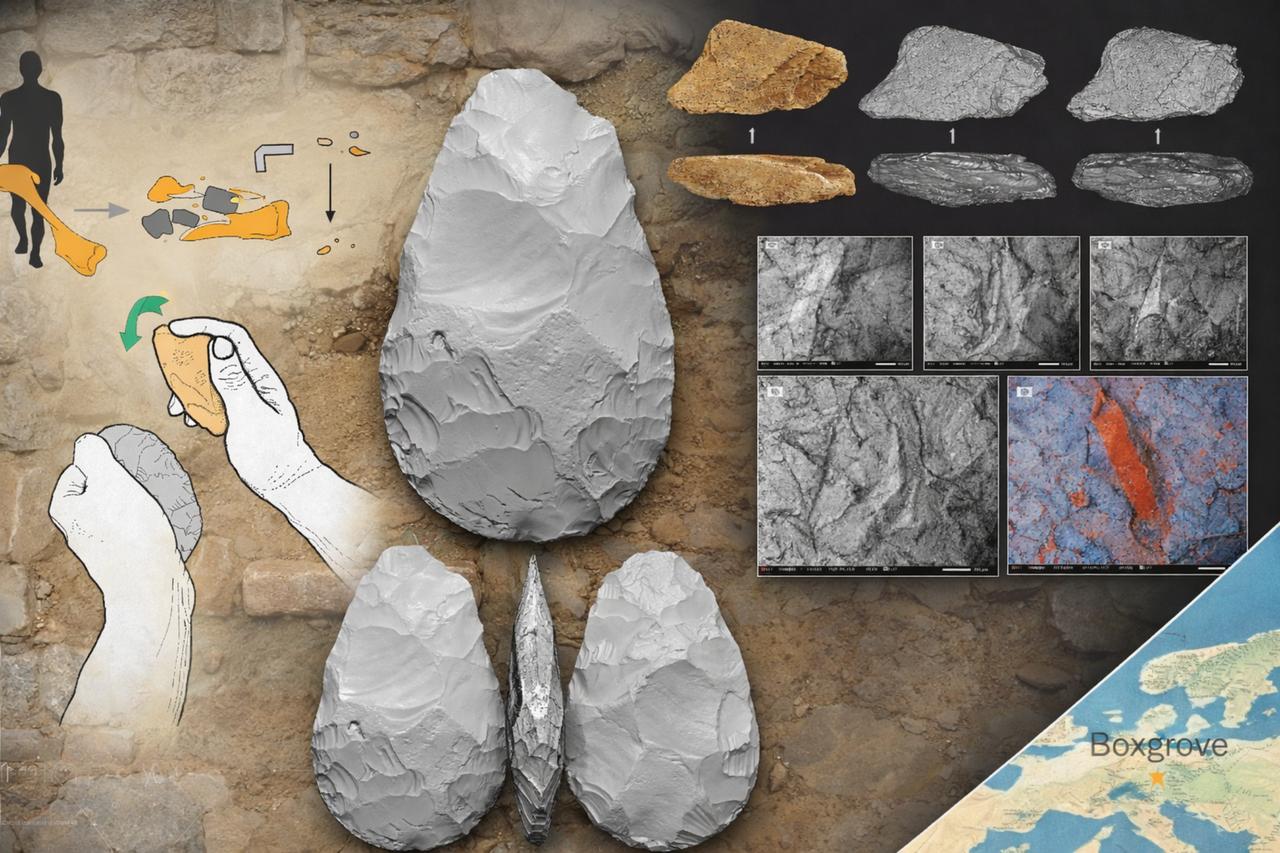

In stone tool studies, “knapping” refers to shaping stone by striking off flakes, while a “soft hammer” is a softer striking tool, often made of antler or bone, that helps knappers take off controlled flakes compared with harder stone hammers. A “percussor” is the striking implement itself, and a “retoucher” is a type of tool used to freshen up or reshape an edge by applying repeated, lighter impacts. The study focuses on a cataloged specimen housed at the Natural History Museum in London, described as a tabular fragment of elephant cortical bone (the dense outer layer of bone).

Researchers describe the object as roughly triangular, measuring 109 millimeters in length, with a thick outer compact-bone layer that grades into spongy bone toward the inner surface. They add that its edges and surfaces appear unabraded and well preserved, aside from limited excavation damage.

While the specific proboscidean species at Boxgrove cannot be pinned down from the available remains, the researchers point to two likely candidates known from other early Middle Pleistocene sites in Europe: the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) and the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus).

The researchers also describe fine scratches and striations tied to the stone edge sliding across the bone before biting in, as well as “plastic” deformation along parts of the damage. They interpret that deformation as consistent with the bone having been relatively fresh (often called “green” bone), meaning it still retained enough collagen to remain pliable at the time it was used.

Because the impressions are described as relatively shallow compared with some other bone hammers from Boxgrove, the authors link the elephant-bone tool to lighter blows used for tasks such as final-stage thinning or edge modification, and they note that small resharpening flint debris at the find spot lines up with an interpretation focused on touch-up work on a blunted edge, such as on a handaxe.

The study frames the tool’s story as a sequence of steps, starting with obtaining a suitable blank and then shaping it through intentional flaking to create an implement that could be held in the hand. It adds that the absence of preparatory bone flakes in a nearby excavated trench suggests that this shaping phase likely happened elsewhere, after which the tool was transported to the location where it was used on flint.

The authors also stress that elephant bones appear to have been rare within the excavated and sampled area of the Boxgrove coastal plain, which they interpret as pointing to sourcing beyond the immediate vicinity. In their reconstruction, the tool was likely used during knapping activities at a butchery site and then discarded.

Bone, antler, and wood tools are described as essential to early human toolkits, yet they are often missing from the archeological record because they do not preserve as readily as stone. Against that background, the authors argue that the Boxgrove find is notable both because it is presented as the earliest known use of elephant bone as a raw material in Europe and because it is described as the earliest unambiguous reported example of elephant bone being used as a knapping percussor.

They also set their argument within a longer-running discussion about whether Lower and Middle Paleolithic osseous tools were mostly ad hoc items used briefly and then left behind, or whether some reflect more deliberate curation and transport. In that context, the study notes that earlier thinking held that “only Upper Paleolithic and Later Stone Age populations routinely turned bone and related substances into unequivocal artifacts within a curated technological framework.”