The latest talks between the Turkish government and the imprisoned PKK ringleader, Abdullah Ocalan, face multiple logjams as both sides are hitching their wagons to a new amnesty law.

But could a single piece of legislation be enough to salvage the latest peace process, often called “terror-free Türkiye,” which is dealing with multiple stakeholders?

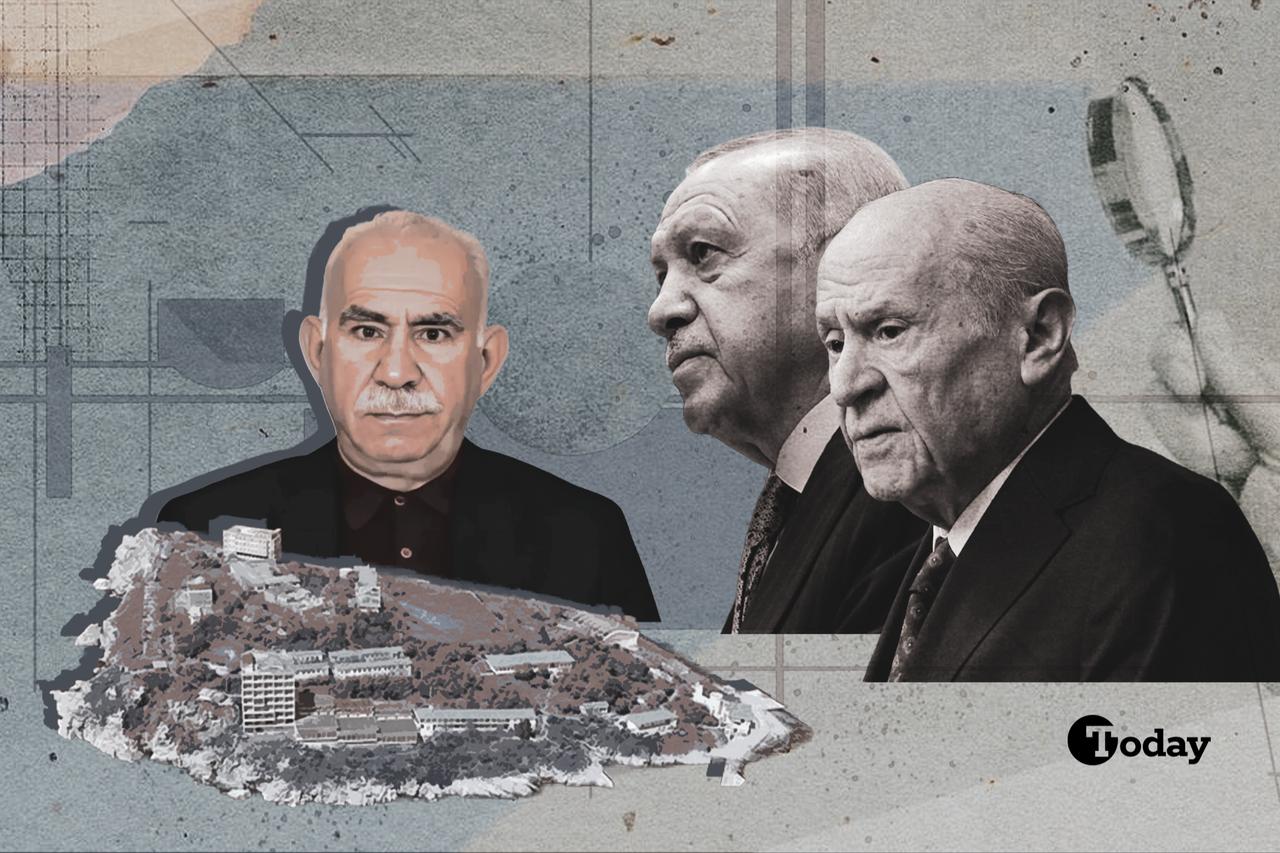

After all, popular support is mediocre, and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan seems less than enthusiastic about the outreach to Ocalan and his PKK, which Türkiye, the United States and the European Union list as a terrorist group.

In addition, the question of which political leaders would be able to guide the process in the long term remains open.

Meanwhile, Ocalan appears coy about his release as a condition for full disarmament, even though senior PKK members in northern Iraq are driving a hard bargain with the Turkish government over their leader’s release.

Further complicating the matter is the PKK’s Syrian branch, the PYD and its armed wing YPG, together with their U.S.-backed front, the SDF, which are still resisting integration with Syria’s central government led by President Ahmad al-Sharaa, whom Ankara is backing.

The latest round of talks between Türkiye and Ocalan began in October 2024. It was when Devlet Bahceli, chairman of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and a close ally of Erdogan, declared that if the PKK leader were to call upon his organization to disarm, he should be allowed to do so from the Turkish Parliament, suggesting that Ocalan could be released from prison.

The announcement shocked many as Bahceli was a vehement opponent of the failed “peace process” from 2012 to 2015 and quite critical of Türkiye’s Kurdish party, the Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM), and its predecessor, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

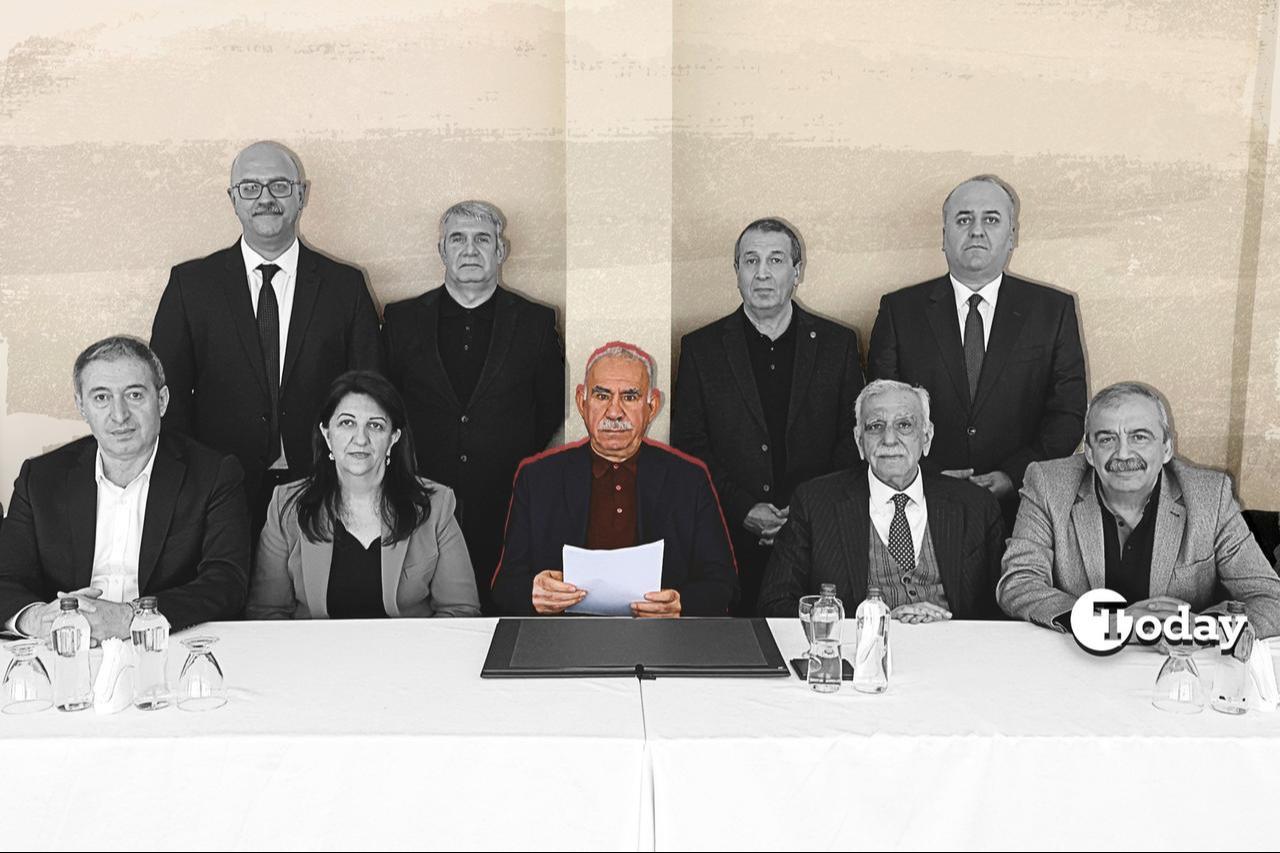

Ocalan acted on Bahceli’s call on Feb. 27, although he made his declaration not from the Turkish Parliament but from his prison on Imrali island in the Sea of Marmara, surrounded by representatives from DEM, calling on his followers to disarm.

Less than three months later, the PKK, perched up in the mountains of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq, announced that it was heeding its leader’s call, holding several “weapons burning” ceremonies.

These developments raised hopes that one of Türkiye’s most intractable conflicts might be coming to an end. Understandably, the country’s Kurdish citizens, half of whom live in the country’s southeastern and eastern regions and who have suffered the most from the violence that claimed about 40,000 lives since 1984, are still enthused about the prospects for ending the conflict.

Why the gloomy outlook, then?

Turkish citizens still remember how the previous “peace process” in the mid-2010s ended in violence, killing hundreds and displacing tens of thousands—they do not want to see that again.

While four out of five Turkish Kurds support the current process, according to Reha Ruhavioglu, the director of the Kurdish Studies Center in Diyarbakir, research by the Ankara-based Institute of Social Studies reveals that the country is evenly split between those who find the “terror-free Türkiye” process as “beneficial” and “not beneficial.”

Türkiye Today reported similar results recently.

To alleviate concerns, the Turkish Parliament formed the “National Solidarity, Peace, and Democracy Commission” last summer. The commission’s official mandate is to “completely remove terrorism from Türkiye’s agenda, strengthen societal integration, fortify national unity and brotherhood, and carry out studies in the field of liberty, democracy and the rule of law.” Although most of its work so far has involved listening to citizens whose lives were affected by the fight against the PKK—relatives of Turkish servicemen and women, as well as Kurdish civilians who lost loved ones and livelihoods, or whose children were kidnapped by the PKK.

The new amnesty law, officially called “homecoming law,” envisions the reintegration of PKK cadres who have not been involved in violence to the general public or, if they are already in prison, to be released on parole.

President Erdogan and his ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) are reiterating that there is no “amnesty,” a term highly unpopular in Türkiye because of its association with the rise in crime rates whenever there was a mass amnesty in the past.

Yet, Turkish society is skeptical about the wisdom of any “PKK homecoming” because of its senior leaders’ awkward victory laps. Save for its organized crime networks involved in human and narcotics trafficking, the group has been eradicated from Turkish territory.

Similarly, its ability to infiltrate across the Turkish border from Iraq or Syria is nonexistent thanks to the joint efforts by the Turkish Armed Forces, the Turkish National Police and Gendarmerie, and the National Intelligence Organization.

Two senior PKK leaders, however, took a gratuitously defiant tone recently. Speaking to Agence France-Press (AFP), one of the PKK’s spokespersons, Fehmi Atalay (codename, Amed Malazgirt), announced that the group “would not take any new steps” until the Turkish government released Ocalan (a position untenable for the Erdogan government until the PKK is fully disarmed, along with its financial and organized crime branches).

Atalay also noted that the group “burnt their weapons only symbolically and did not surrender them,” which to Turkish ears sounded like a warning of possible renewed armed conflict.

Meanwhile, statements by Hulya Oran (codename, Bese Hozat), another PKK leader, almost confirmed a suspicious Turkish population.

Oran said PKK cadres were not seeking “amnesty” because “they did not commit any crimes and had nothing to atone for.” Especially Hozat’s argument that their armed conflict constituted a “democratic struggle” and that the struggle would continue after they returned home made a mockery of the whole idea of peace. To most Turks, it sounded like she and her ilk would merely use the amnesty law to reposition themselves in Türkiye and stage attacks from within.

Here, it is worth mentioning that Turkish Kurds made the greatest gains in cultural and political rights whenever the guns fell silent for an extended period, especially in 1999-2003 and 2012-2015, so one wonders how useful the PKK is to Kurdish gains.

Retired Turkish Army officer Abdullah Agar, an influential public commentator when it comes to PKK terrorism, spared no words against Hozat, reminding his audience what the group had done in the past: “To say ‘we committed no crime’ means that attacking villages is not a crime. Killing children is not a crime. Massacring teachers and hanging them on flagpoles is not a crime. It means fooling children and youth and recruiting them to (the PKK) is not a crime.”

Bahceli was less emotional but equally frustrated at Hozat. “Nobody is promising an amnesty. Their crimes are sealed in the ‘consciences of the afterlife.’” Bahceli took her to task for taking such an extreme tone that conflicts with Ocalan’s seemingly more conciliatory tone.

The two PKK leaders’ statements and the reactions highlight one of the fundamental paradoxes facing both Türkiye and the country’s Kurdish movement, and why an amnesty/homecoming law might not be enough to end the conflict: everyone—ranging from Turkish nationalists (such as this author) to MHP to DEM Party and the PKK itself—claims to speak for Kurds.

That is a problem because Kurdish citizens’ legitimate demands for cultural and political rights (never mind a civil conversation about regional autonomy, which is highly unlikely at this point) get mixed up with the PKK and its violence.

In a world where the word “terror” is as popular as the COVID-19 virus, presenting Ocalan, the PKK, and its umbrella organization, KCK, as the sole advocates of Kurdish rights, creates an ideational link between any expression of Kurdishness and terrorism.

Iraqi Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani found himself in the metaphorical crossfire of these disputes on Nov. 29, when he visited the Turkish town of Cizre with a majority Kurdish population, near Türkiye’s border with Iraq on Nov. 29.

Barzani, the former KRG president and long-time partner of Ankara (and close ally since the late 2000s) and often at odds with the PKK for the latter’s leftist politics, arrived in Cizre for a cultural event with his close protection squads donning black uniforms with shoulder patches featuring the KRG flag and carrying automatic rifles.

It is because the PKK uses the same red-white-green-yellow colors on its banners as the KRG flag, although in a radically different pattern, that many Turks often identify the group’s symbols with those of Iraqi Kurds.

Amid uncertainty over PKK disarmament, images from Cizre sparked outrage on Turkish social media, fueled by the public greeting to Barzani. Even the now pro-Kurdish Bahceli called the images “against protocol and inappropriate,” while continuing to support the new peace process.

Türkiye’s Interior Ministry announced an investigation into the incident and senior presidential aide and former AK Party MP Mustafa Akis pointed out that, as a former KRG president, Barzani was entitled to a protocol similar as that afforded to former Turkish presidents and prime ministers when they go on overseas trips, where their bodyguards do not wear uniforms nor do they carry firearms other than pistols.

The Iraqi Kurdish administration in Erbil tried to manage the outrage by pointing out that Turkish security personnel also carry automatic weapons when Erdogan or other Turkish leaders visit Iraq and the KRG.

Unfortunately, Barzani was less considerate in his response. According to the BBC’s Turkish service, he said, “We had thought that Allah had given guidance to Bahceli (and) rid him of racism and chauvinism.”

Some of the more extreme elements of Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party think the PKK is a scheme propped up by the Turkish “deep state” to undermine the Kurdish movement in Iraq.

Stuck between his regional Kurdish partner and his political ally at home, President Erdogan described Barzani’s statements against Bahceli as “inappropriate and disrespectful” at his party’s parliamentary group meeting on Wednesday. AK Party Spokesman Omer Celik called them “unacceptable.”

Another dynamic that explains why the new “peace process” idea has not made much progress is that Türkiye is repeating some of the mistakes from 2012 to 2015—especially by focusing on the personal fortunes of individual leaders instead of setting clear principles and red lines.

In the mid-2010s, a tacit agreement between the AK Party and the PKK had the HDP backing Erdogan’s bid for extended presidential powers.

In exchange, Ocalan’s prison conditions were to be improved and HDP-run municipalities in the southeast were granted greater authority. This could involve releasing Ocalan and giving more powers, short of full autonomy, to the municipalities.

Selahattin Demirtas, then-chairman of Türkiye’s leading Kurdish party HDP, DEM’s predecessor, had different ideas. Calculating (correctly, at first) that his party could gain more votes by opposing Erdogan than supporting him, Demirtas said his party would not let Erdogan get his powerful presidential system.

HDP entered parliament as the third largest in the June 2015 elections and AK Party lost its majority, which triggered the PKK to resume armed conflict in the fall of 2015. In November of that year, repeat elections eroded HDP’s edge, returned the AK Party’s parliamentary majority, and solidified the budding partnership between Erdogan and Bahceli.

Following the failed coup attempt of July 15, 2016, Erdogan won his executive presidency in a popular referendum while Demirtas found himself in jail for instigating the “Kobane riots” that killed over 50 people in southeastern Türkiye in October 2014.

Around the same time, popular uprisings in Syria had turned into a full-fledged civil war, where the YPG, with Western backing, had begun to make considerable gains against Daesh. In this context, the PKK tried to attack several Turkish towns on the border with Syria and Iraq, suffering major defeats within from Türkiye, from which it never recovered.

While most commentators think a similar “leadership” dynamic is at play today, that could be misleading in Türkiye’s current political scene.

Unlike 2012-2015, when Erdogan was in a fight both to keep his political fortunes and rid the state of the followers of his archnemesis, Fethullah Gulen, the leader of the Fetullah Terrorist Organization (FETO) cult, which would go on to stage the 2016 coup attempt, the Turkish president looks anything but insecure at home or abroad these days.

The various regional conflicts in Türkiye’s neighborhood have turned Erdogan into an indispensable geopolitical partner for all sorts of stakeholders—Americans, Europeans, Africans, Asians, Russians, Iranians, Syrians, Gulf Arabs, and, yes, Kurds.

In addition, Erdogan appears surprisingly agnostic about running for a fourth term in 2028, even though he might not face a serious challenge from most opposition candidates except for Mansur Yavas, the mayor of the capital Ankara. Former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu remains in jail.

Earlier this year, Erdogan said he “was not troubled about running again,” even after Bahceli urged him to do so. No Turkish president since the third president of the republic, Celal Bayar (1950-1960), has served over three terms.

As for Bahceli, who appears to be running point in the talks with Ocalan and has demonstrated a surprising degree of understanding toward the PKK leader and Türkiye’s Kurdish politicians in a way that would have been completely out of place only a few years ago, is turning 78. Once a fiery rhetorician—a characteristic that still manages to come out—Bahceli risks losing votes to other Turkish nationalist parties should the current process fizzle out or worse, blow up as it did in 2012-2015.

The country’s main opposition, the secular, center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), faces similar risks. The party had come in first during the municipal elections in March 2024—the first time AK Party came in second.

Meanwhile, there is also an unspoken, silent cold war between Ocalan and Demirtas. The two men had backed different candidates for the Istanbul mayoralty elections in 2019—Ocalan, the AK Party candidate and Demirtas, the opposition candidate, Imamoglu—and the gulf between them has only widened.

While Ocalan remains “public enemy number one” among most Turks, Demirtas remained more popular among Kurdish voters, although his extended imprisonment and general popular exasperation with the PKK and DEM party have lowered his approval ratings among the general Turkish electorate.

Demirtas has the added advantage of being younger—52 years of age to Ocalan’s 76—he announced his withdrawal from partisan politics following the opposition’s disastrous showing against Erdogan in the 2023 parliamentary and presidential elections.

Another dynamic that challenges “terror-free Türkiye” sits across the border in Syria, where U.S. officials are on record to admitting the “rebranding” of the PKK’s Syrian branch, the PYD/YPG, as “SDF” in the mid-2010s.

Today, save for some Kurdish-majority areas on Syria’s border with Türkiye (of which it lost Afrin to Turkish-backed anti-Assad Syrian rebels in 2018), SDF controls mostly Arab areas, and many of the SDF’s militias are composed of Arabs.

Following the Syrian revolution that toppled the Assad regime on Dec. 8, 2024, popular uprisings took place in Arab towns such as Raqqa and Deir ez-Zur, which the SDF suppressed by force.

One of the main reasons why Türkiye is so adamant about disarming the PKK is to also neutralize the SDF as a threat in Syria. On Mar. 10, the SDF’s commander, Mazlum Abdi, who is considered to be Ocalan’s adopted child, signed an agreement with Sharaa in Damascus where SDF cadres would be integrated into central government forces in return for Kurdish rights and revenue-sharing mechanisms.

One of Syria’s few revenue-generating assets, the oil and gas fields in the country’s east, are under SDF control.

At present, the U.S. Ambassador to Türkiye, Tom Barrack, whose second brief is US envoy to Syria, is working to bridge the gap between Damascus and the SDF. So far, he has not succeeded.

Türkiye suspects Israel is egging on the SDF to resist integration with Damascus so the Jewish state could extend Syrian territories it occupies in the south and punish Ankara for its support for Palestinians.

This situation could lead to one of the biggest miscalculations on the part of the PKK and the SDF—and the broader Kurdish movement: Overreliance on Israel and the United States.

While Israel could make life difficult for Sharaa and Türkiye, Washington is unlikely to back the Syrian Kurdish group indefinitely, given the U.S. electorate’s exasperation with the “forever wars” in the Middle East. That, in turn, could lead to a Turkish-Israeli confrontation in Syria.

There are still signs of hope. In a detailed report for Independent Turkish, Turkish Kurdish journalist Gulbahar Altas covered a meeting in Germany in late November—far from Türkiye, Syria, or Iraq, where academics, politicians and journalists discussed the ongoing process.

While Altas interpreted the attendants’ physical condition as tired from years of struggle, she said they still expressed hope for peace and wanted to explore ways to have the people of Türkiye live together in peace. It might be the best of Turks from all backgrounds—ethnic Turks, Kurds and others.