This article was originally written for Türkiye Today’s weekly newsletter, Saturday's Wrap-up, in its December 13 issue. Please make sure you are subscribed to the newsletter by clicking here.

December has increasingly become a month of tension, expectations and a war of words between the government and worker unions, almost a ritual in the last few inflation-dominated years. What once unfolded as a technical adjustment in Türkiye's golden years has morphed into a high-stakes negotiation, shaped by inflation anxiety, simmering public frustration and a government determined to keep its disinflation narrative intact. As the first meetings approach, the atmosphere is already thick with competing demands and carefully calibrated messages.

This year’s debate unfolds under the shadow of a minimum wage that directly affects an estimated 9.5 million workers. With their families, you can imagine how large a share of Türkiye’s 86 million population that is.

The figure functions not only as the country’s lowest salary but as a benchmark shaping wage expectations across the broader economy. Rising living costs, stubbornly high inflation categories and the widening gap between wages and the hunger threshold have all sharpened the stakes. Even with headline inflation easing to 31.07% in November, households continue to feel the strain, and that discomfort now sets the tone for the negotiations.

Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek’s stance is well known: steady disinflation first, wage adjustments second. As reported by Türkiye Today economics editor Onur Erdogan, Simsek himself plays no formal role in determining the minimum wage increase rate. But his approach, which is to favor modest increases guided by 12-month inflation expectations rather than current inflation, shapes the spirit around the talks. Simsek has repeatedly emphasized that price stability is the only sustainable path to improving workers’ purchasing power, arguing that outsized wage hikes would ultimately be eroded by renewed price spirals. He has a point, but people have realities to face when they stand in front of their (mainly) three-lettered supermarket shelves.

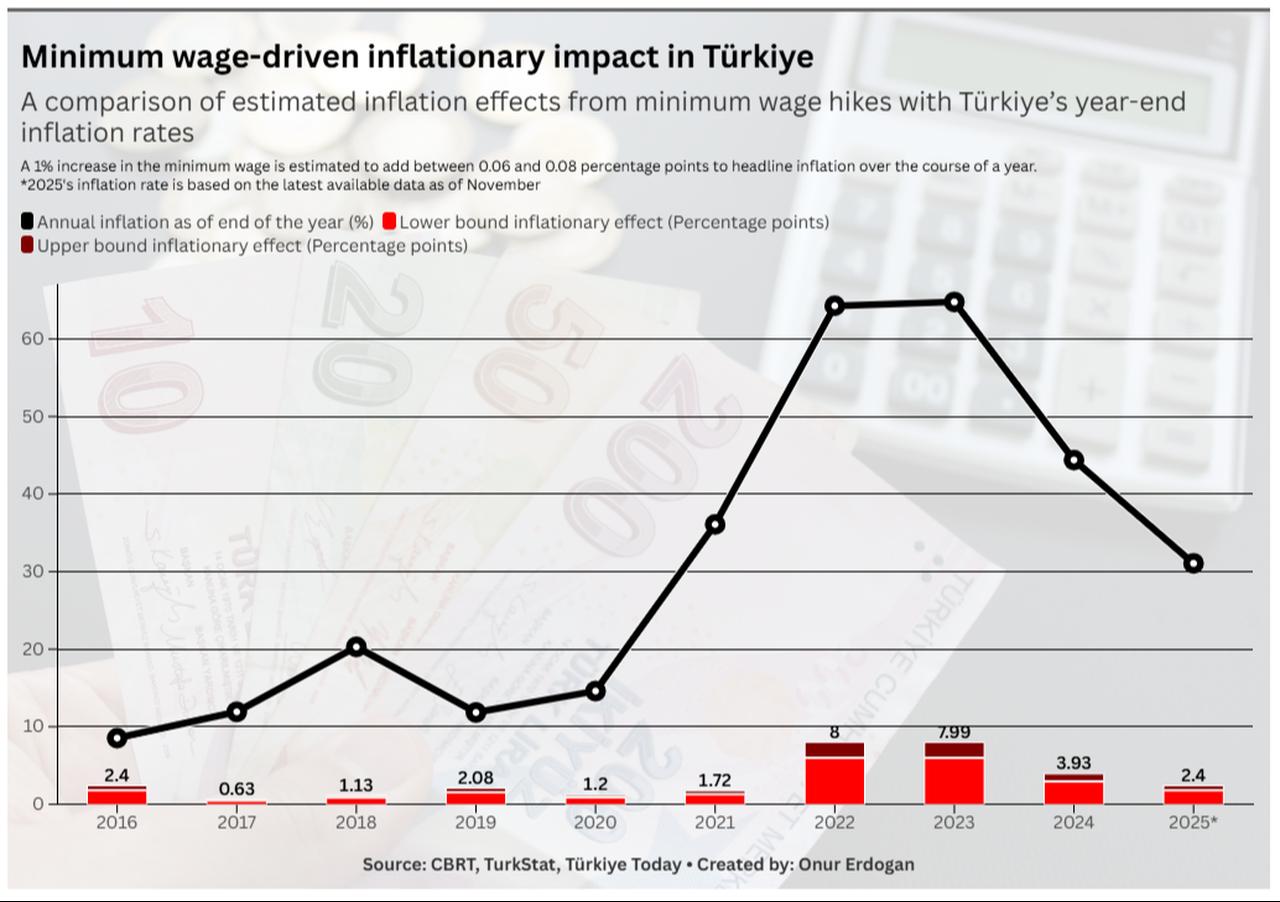

Simsek's caution reflects the broader economic philosophy he has overseen since mid-2023: tight monetary policy, a slower pace of adjustments and the abandonment of the biannual update mechanism used during the turbulent years of 2022 and 2023. The central bank’s own modeling suggests that every 1% increase in the minimum wage can add up to 0.06 to 0.08 percentage points to inflation.

The formal process for minimum wage increase has now begun. The 15-member Minimum Wage Determination Commission, five from the government, five from labor, five from employers, is expected to hold three or four rounds of talks before the final announcement on Dec. 31. The ministry-appointed chair casts the deciding vote in case of a tie, a feature that has long drawn criticism from unions.

Market expectations currently center around a 20%–25% increase, aligned with forward inflation projections. J.P. Morgan anticipates a 23% adjustment. That would lift the gross minimum wage to roughly ₺27,187 and add an estimated 1.4–1.8 percentage points to inflation over the following year. As the calendar edges toward year-end, Türkiye once again finds itself balancing workers’ immediate needs against policymakers’ long-term goals. The December ritual will unfold as it always does: tense, crowded with expectations and defined by words as much as numbers.

Since this week’s topic has been about economics, I would like to note that renowned British economist Timothy Ash will be penning regular articles for Türkiye Today on the country’s economy.