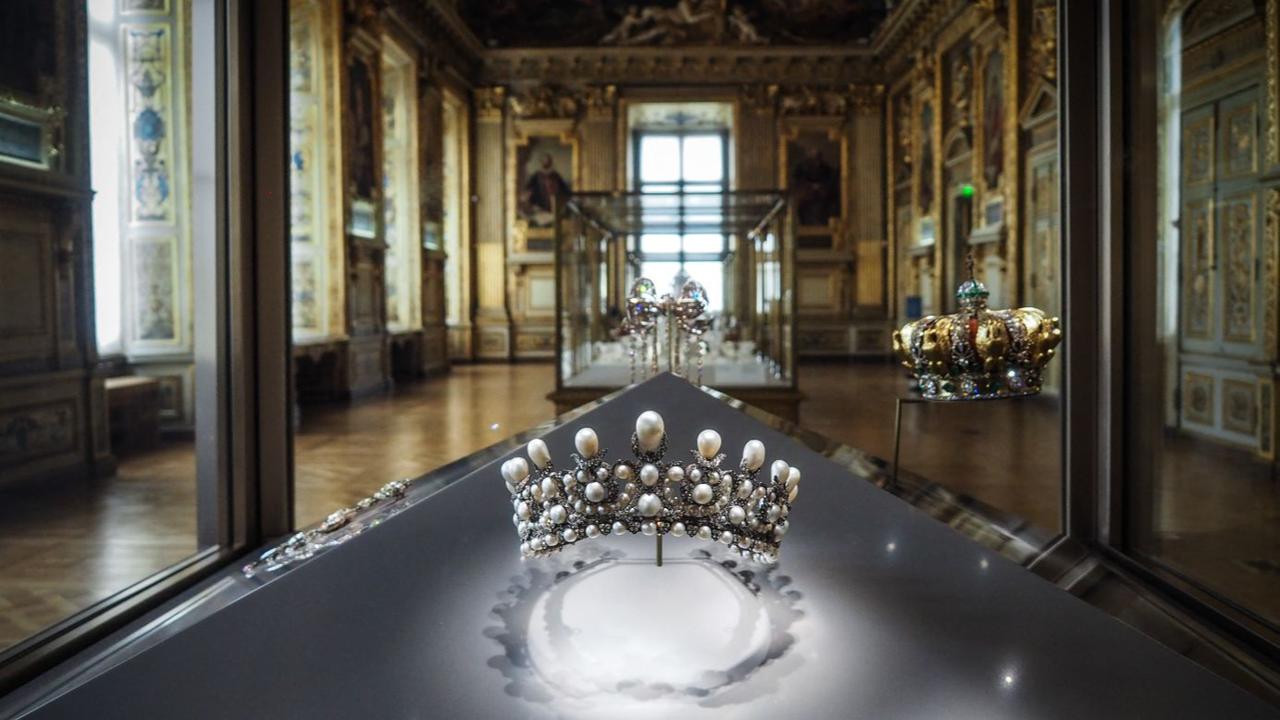

Last week, a construction vehicle pulled up to a window overlooking the Louvre’s Apollo Gallery. In October, a similar sight meant something very different. This time, the machine was there for its intended purpose, installing iron bars as a visible countermeasure after the historic theft valued at about €88 million, when a crew working under the cover of daytime routine exploited access, speed, and disguise to strike one of the world’s most iconic museums.

Alongside the Louvre case, a separate theft scandal linked to the Elysee Palace has reinforced the sense that France, already politically turbulent, has spent months in the spotlight not only for domestic headlines but also for a global problem that never truly disappears: high-value cultural property crime.

As new reporting clarified key elements of the Louvre investigation early this week, the picture that emerged was less cinematic than structural. A small crew, dressed like workers and using heavy equipment, appears to have turned basic vulnerabilities into a short, violent burst of entry and removal. They benefited from routine trust, weak perimeter friction, and the reality that even elite institutions struggle to match the tempo of a fast crew once the breach begins.

Art crime is not a single category. It sits at the intersection of museum theft, fraud, trafficking, and, increasingly, financial crime such as money laundering and sanctions evasion.

To understand what the Louvre case reveals about that wider ecosystem, I examined the case with Tim Carpenter, a former FBI Supervisory Special Agent who led the FBI Art Crime program.

In its earliest form, the FBI Art Crime Team focused primarily on high-value art thefts. As he explains, the program began as “a specialized initiative within the FBI’s Major Theft Program,” reflecting a narrow emphasis on traditional theft cases rather than the broader art-market crime ecosystem.

Over time, that focus changed.

“The Art Crime Program began to concentrate on other crime trends within the art market, such as fraud, which actually represents a very large part of the portfolio these days, antiquities trafficking, money laundering, and sanctions evasion.”

That evolution led to a major institutional restructuring.

“As the head of the Art Crime Program, I successfully pulled the program out from under Major Theft and had the FBI designate it as its own standalone program—recognition of the broad categories of violations that we were looking at.”

The following year marked another turning point, when he made money laundering “the priority of the program,” reframing art crime investigations around financial flows and organized networks rather than individual stolen objects.

Around the same time, the Art Crime Program was folded into the FBI’s Transnational Organized Crime Section, a move he called “the right fit for the program, given the transnational nature of art crime.”

Despite this shift, he observes that public perception has remained largely unchanged. “When most people think of the work the FBI’s Art Crime Team does,” he said, “they naturally think about heists like the Gardner or the Louvre.”

In reality, he stressed, “while we certainly work those cases, they actually make up a small percentage of the real work.”

Given that “the U.S. is by far the largest art market in the world, both licit and illicit,” international partners frequently called on the FBI to assist with recoveries and complex investigations.

Asked which cases are most draining, he is unequivocal.

“By far, long-term cases like the Don Miller investigation are a serious drain on resources. We recovered thousands of artifacts and items of cultural property, each of which had to be properly stored, inventoried, condition-reported, and maintained, sometimes for as long as a decade. The FBI is not the Smithsonian, and we don’t have the museum resources typically employed to care for such collections.”

In the immediate aftermath of the Louvre theft, much of the public discussion leaned toward a familiar narrative of sophistication and cinematic precision. That reading, however, does not hold up under closer scrutiny.

As he puts it, “they didn’t parachute in, or tunnel in from underneath. They didn’t scale the side of the building with special forces equipment and cut their way in with laser cutters.” What actually happened was far more basic.

“They climbed a ladder and used angle grinders to get in. This was nothing more than a brute-force attack on a vulnerable entry point.”

While he acknowledged that the perpetrators had done some preparatory work, he is clear about where the line is drawn.

“For sure, they had done their homework,” he said, “but this wasn’t Mission Impossible.”

In his assessment, the only genuinely sophisticated element of the operation was the choice of target itself.

“Movies and television make us think that art thieves are highly sophisticated,” he said, but “overwhelmingly, reality shows us otherwise—art thieves are just thieves.”

In practice, he said, “they are often the same guys who are burglarizing houses for guns, drugs and money, or breaking into warehouses to steal televisions.”

The execution of the Louvre theft reinforces that assessment. “They might have had a good plan,” he noted, “but their execution was poor.” The most telling indicator was the amount of evidence left behind. “The fact that they left behind so much evidence made it clear this wasn’t some highly capable professional crew.”

In his view, this level of sloppiness is not an anomaly but typical of opportunistic crews acting under pressure.

From Carpenter’s point of view, the speed of the investigation was not surprising. “I am not the least bit surprised that these were local thieves,” he said, adding that he was confident French authorities would make quick arrests.

At the same time, he cautioned that the case may not be fully closed. “I think more arrests will come in time as they continue to unravel the case,” and investigators, he adds, “still can’t discount the possibility of some insider help, whether witting or not.”

On motivation, his reading is equally unsentimental. This was not a months-long, carefully engineered caper in the tradition of The Thomas Crown Affair or The Italian Job. “Most art thieves are opportunistic—and I think these were no different,” he says.

The pattern is familiar: “they find a vulnerability and they exploit it,” and “it’s almost always simply for monetary gain.”

The Louvre investigation revolves around a single priority: preserving the crime scene, something that is simple in theory but far more difficult in practice in a public space like the Louvre.

As he explains, “proper preservation of the crime scene is imperative,” yet it is often compromised because “victims or other first responders can destroy forensic evidence in their haste or panic to stabilize the scene.”

In this case, however, he believes responding police “did a good job in getting the scene secured and immediately beginning to collect trace evidence.”

From there, the investigative logic follows a disciplined sequence.

“We would look for forensics starting at the first point of entry,” he explains, “and work toward—or from—the actual site of the theft.” In the Louvre case, that meant beginning with the mobile lift they used to position a ladder at the entry point, and moving inward toward the display case.

Along that path, investigators would systematically search for “fingerprints, hairs, fibers, DNA, blood, skin cells, and other obvious trace evidence.” CCTV footage, if available, plays a critical role, not only in reconstructing movements but in “helping guide the search for trace evidence by establishing actions and routes.”

The scope of the investigation then widens rapidly. “We would want to interview everyone present,” he says, explicitly listing “museum staff, visitors, pedestrians, and business owners outside the museum.” Surveillance review is equally expansive in scope.

“We would review all CCTV footage, not only inside the museum but from business and government cameras outside the museum in a wide footprint.”

Crucially, that review is not limited to the moment of the crime. Investigators would go back “days, weeks, and perhaps even months before” to determine whether the facility had been cased in advance.

At the same time, attention turns inward. “We would look at internal staffing to see if there were any insider threat concerns,” he explained, making clear that insider dynamics are a standard line of inquiry rather than an afterthought.

Parallel to this, investigators would “begin to work confidential informants to develop information,” while immediately coordinating with partner law enforcement agencies “both domestically and internationally” to share intelligence and strengthen the overall source base.

Technical and open-source tools also come into play early. He points to the use of “OSINT tools—geo-fencing, cell dumps, and similar methods—to establish what devices were in the area and work back from those.”

Had the crew avoided biological traces, controlled secondary transfers, and limited exposure through vehicles and communications, “the landscape would be quite a bit different,” he added.

When it comes to the fate of the stolen jewels, he describes the situation as “the million-dollar question,” noting that everyone immediately wants to know what happened to the objects in the hours and days after the theft. From his perspective, there are only a limited number of realistic paths forward.

“The worst-case scenario is that the jewels were immediately broken apart,” with precious metals melted down and individual stones recut or separated for easier movement into the gemstone market.

He adds that this is “certainly the most concerning scenario,” though he is skeptical it happened right away in the Louvre case, since “the thieves made so many mistakes” and were “almost certain to be apprehended.”

A second possibility is ransom. He noted that the idea of holding iconic objects with the intention of negotiating their return may sound far-fetched, but it is not without precedent.

There have been cases where stolen cultural objects were later leveraged in this way, even if ransom was not the original motive at the time of the theft. While he personally considers this outcome unlikely, he emphasized that it cannot be dismissed outright.

A third scenario, and the one he finds most plausible, reflects how offenders often adapt once they realize they are about to be caught. Because the perpetrators “had to know they were likely to be arrested,” he suggests they may have hidden the jewels with the intention of using them as bargaining chips.

In this reading, returning the objects—“as undamaged as possible”—offers leverage in negotiations with prosecutors.

Destroying the pieces would eliminate any such leverage and virtually guarantee maximum sentences. He noted that this pattern has appeared repeatedly in similar cases, which is why this scenario carries particular weight in his assessment.

A fourth possibility, he adds, is that some or all of the jewels have already been recovered, but that recovery has not been made public. From an investigative standpoint, keeping such information quiet can be deliberate.

Law enforcement may choose not to announce a recovery while efforts are still underway to identify co-conspirators, including potential insiders.

As he points out, in similar circumstances the FBI itself would likely “keep recovery quiet” until the broader investigation was fully concluded.

Timing, he says, works against investigators. “Generally, time is the enemy.”

The longer an investigation takes, the greater the risk that objects will be dismantled or dispersed.

That said, he cautions against assuming that delay automatically means loss. He points to past cases where recovery occurred years later, reinforcing the idea that patience and pressure can still produce results.

Moving stolen jewels into the market poses different challenges than moving stolen artwork.

Jewelry is easier to break down and distribute, making individual stones extremely difficult to track once they enter circulation.

While reputable dealers may flag suspicious gemstones, he notes that “there are many unscrupulous dealers who won’t ask questions,” and that once stones are sold individually, identifying them later becomes “exceedingly difficult.”

Ultimately, he argues that the biggest obstacle facing criminals in cases like this is not logistics but trust. “They are criminals, and they move within the criminal world,” he says, meaning every transaction carries the risk of betrayal.

With so much attention focused on the stolen jewels, even black- and grey-market actors may hesitate to absorb that level of risk.

In his view, that pressure combined with arrests and investigative scrutiny often proves decisive in determining whether stolen objects resurface or disappear permanently.