The SDF is facing an uncertain fate and huge potential losses in 2026. Since the fall of the Assad regime in late 2024, the group has dragged its feet over integrating its forces and territory with the new central government in Damascus led by President Ahmad al-Sharaa.

The March 10 framework agreement between Sharaa and SDF ringleader Mazlum Abdi envisioned the reintegration of SDF-controlled regions in the northeast—about one-third of Syria’s land mass that also contains most of its water, agricultural lands, hydropower, and oil and natural gas—to the rest of the country in exchange for the recognition of Kurdish rights and limited regional autonomy.

The deal has yet to be implemented, and Abdi is likely going to escalate the situation by rejecting the Sharaa government’s latest offer to implement the March 10 deal through a phased integration of SDF units into the new Syrian military as three army divisions in return for the deployment of regular Syrian forces into northeastern Syria.

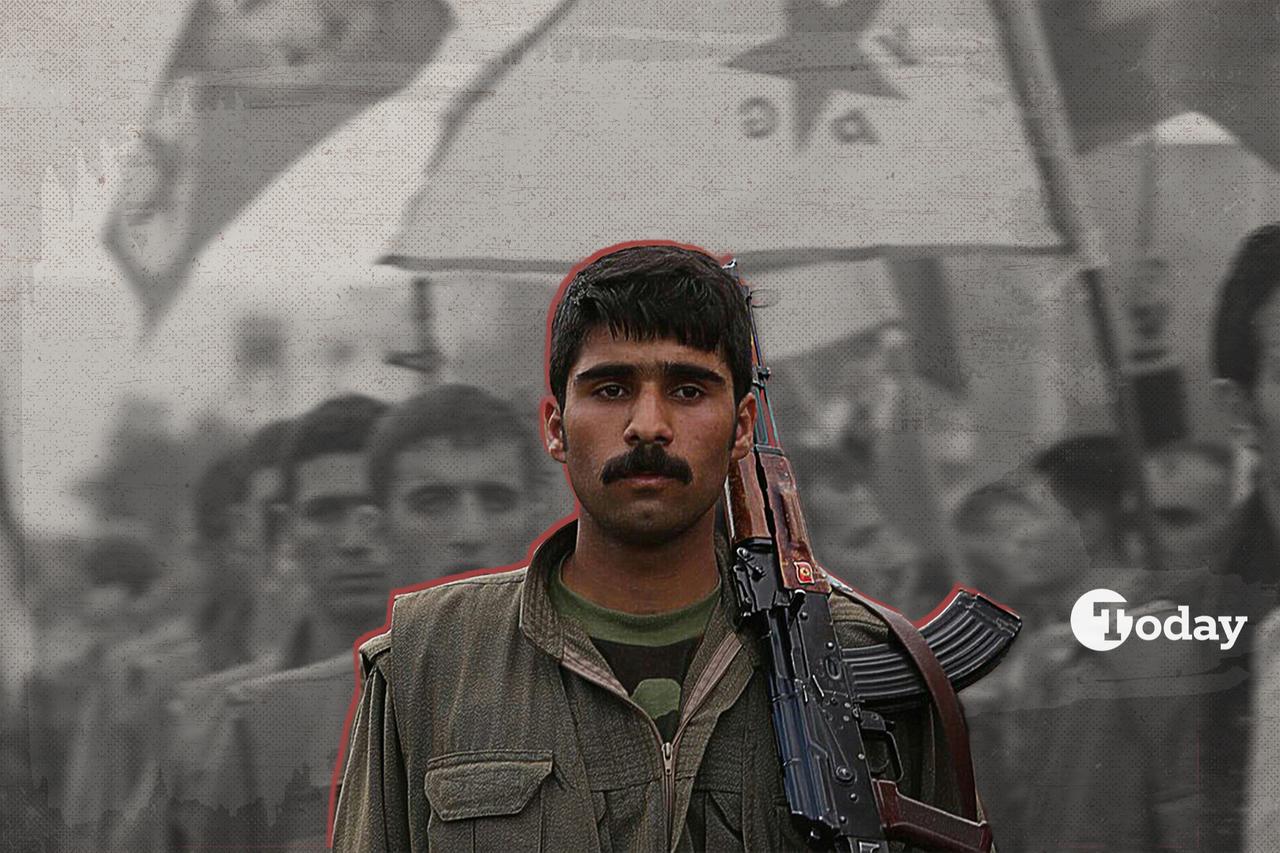

The SDF warns Damascus and its main backer, Türkiye, not to engage in a military operation, claiming to have 70,000 to 100,000 fighters and U.S. backing.

The SDF’s current problems—its inconsistencies, overreach, and dependence on outsiders—stem from long-term issues dating back to before the Syrian civil war. These challenges undermine the group’s hand vis-a-vis Damascus and risk broader political and geographical losses.

Perhaps the SDF’s most fundamental problem is its attempt to be everything to everyone, which leads to what one might call an “authenticity or sincerity gap.”

Take the beginning of the civil war in 2011-2012, when SDF’s lead group, the PYD and its armed wing, YPG, reached a tacit understanding with the Assad regime in Damascus to take over large tracts of territory on the Turkish border. At the time, Bashar al-Assad wanted to punish Ankara for supporting the Syrian opposition.

Throughout the civil war, the SDF flew the Assad regime’s red-white-black flag with two green stars together with its own banners and coordinated its activities with the regime—until, that is, the HTS-led armed opposition’s successful revolution on Dec. 8, 2024, that toppled Assad, after which SDF hoisted the new Syrian flag.

This “authenticity crisis” has left the SDF with almost no genuine allies in the region.

If you want to know the SDF better, just ask the Kurdish National Council of Syria (ENKS), a close ally of Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party, the lead party in Iraq’s Kurdish Regional Government (KRG). Following its tacit agreement with the Assad regime in 2012, PYD/YPG refused to allow ENKS’s “Roj Peshmerga” to take positions in Syria. When the ENKS refused to recognize the PYD’s “autonomous cantons” in 2014, ENKS cadres faced arrest and assassinations at the hands of the YPG.

Only after Daesh attacked the town of Ain al-Arab on the Turkish border in 2014 did PYD/YPG accept Barzani Peshmergas’ help

Speaking of Daesh, while the SDF portrays itself as the main actor in ending the so-called “caliphate” in 2017 (and that’s not necessarily wrong), the group wouldn’t want you to know that PYD/YPG refused to take on Daesh until the fateful summer of 2014 when Daesh began is its massive onslaught and took over a quarter of Iraq and nearly half of Syria by 2015.

Another reflection of SDF’s “crisis of sincerity” is that, although the group includes Arab militias (many of which joined the PYD/YPG on account of U.S. support), Turks and Arabs see the SDF as too much of a Kurdish nationalist group that aims to dismember Türkiye, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, while many Kurds perceive the group as too leftist and inadequately nationalistic.

A related issue is that PYD-YPG is the Syrian offshoot of the PKK, which has fought the government of Türkiye since the early 1980s for independence and autonomy at various points and is listed as a terrorist organization by Ankara, the United States, and the European Union. In parallel with the PKK’s jailed ringleader Abdullah Ocalan calling for his group’s disarmament since February, the Turkish government is expecting the SDF to join Damascus.

Abdi’s recent announcement calling for the “unification” of the “four parts of Kurdistan in 2026” risks upending Syria’s relative stability and spillover effects into neighboring countries.

The authenticity/sincerity problem has manifested itself not only through SDF and PYD/YPG’s odd strategic preferences—first striking against fellow Kurdish ENKS instead of Assad or leaving Daesh alone until it had metastasized in 2014-2015—but also in terms of ideas.

Part of the SDF’s problem is its awkward attempts at mixing advocacy of Kurdish rights with Ocalan’s odd transition from Maoist “people’s war” and Stalinist practices (during the 1980s and 1990s, he ordered the execution of up to 15,000 PKK cadres who dared to question him) to a more left-libertarian framework that he calls “democratic confederalism” and advocacy of women’s rights, or “jineology.”

Ocalan turned to “softer” leftism after his capture in Kenya by operatives from Türkiye’s National Intelligence Organization, MIT, in 1999.

Over the years, Syrian Kurdish friends and acquaintances of this author—many of them closer to ENKS, the Muslim Brotherhood, or smaller religious parties in the region—have complained about SDF cadres coming to their neighborhoods and villages to spew ideological nonsense and using the visits to forcibly conscript children and youth.

Another inconsistency is the SDF accusing the governments of the four regional countries where Kurds live—Türkiye, Iran, Iraq, Syria—with “ethnic cleansing” but doing the same thing in Syria by refusing to allow Arabs who had been displaced by Daesh to return to their homes—Kurds who are deemed inadequately loyal to the PYD-YPG cause face the same fate.

Meanwhile, even as Kurds only make up about 10% of Syria’s population, the group continues to hold Arab-majority lands in such regions as Deir el-Zour, Raqqa, and Hassakeh province. Following the revolution in late 2024, SDF units fired on civilian Arabs protesting the group’s continued rule in their cities.

Another major limitation for the SDF is that it has come to rely on U.S. advice and training a bit too much. Even its name was foreign-inspired.

In a now-famous story, then-head of U.S. Special Operations Command, Gen. Raymond Thomas, admitted at the Aspen Security Forum in 2017 that the PYD/YPG’s “rebranding” as “SDF” in the mid-2010s came on account of American advice.

This overreliance on the U.S. is probably leading the SDF into a strategic delusion. Ali Burak Daricili, a professor of international relations at Bursa Technical University and a retired MIT officer, has argued in various news outlets that the group is likely exaggerating its claims to having tens of thousands of fighters to skim funds and supplies from Washington—similar to the “ghost soldiers” problem in Afghanistan where battalion and company commanders overcharged the U.S. by bloating the number of troops under their command.

A bigger problem is the story that SDF and its sympathizers tell themselves. While SDF units that did take on Daesh fought bravely, from a strategic and operational standpoint, they would not have enjoyed such success in the absence of U.S. and other allied countries’ air support. In a potential confrontation with Damascus and/or Türkiye in 2026, air support is unlikely to come.

Of course, overreliance is hardly a problem exclusive to the SDF/PKK—other Kurdish movements in the past also trusted and were betrayed by outside actors.

The United Kingdom promised Kurds an independent homeland after World War I, but then forced them to join Iraq, leading to the first Kurdish rebellions in the 1920s and 1930s. At the dawn of the Cold War in 1945-1946, Qazi Mohammed, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, and other leaders of the semi-independent Mahabad Republic in Iran thought they could trust the Soviet Union to back them against Tehran, a dream that came to a swift end in late 1946.

In Iraq, Mustafa Barzani saw massive support from Iran, the United States, and Israel in the late 1960s and early 1970s only to be hung out to dry when the Shah of Iran struck a deal with Saddam in 1975 and withdrew his support for Iraqi Kurds.

Forty-two years later, Mustafa’s son, Masoud, who served as KRG president from 2005 until 2017, misread the mixed signals coming from Western capitals, Israel, and Russia in 2017 and forged ahead with an independence referendum, only to lose to Iraq’s federal government the critical province of Kirkuk, a region without which an independent Kurdistan cannot survive.

Now, the SDF is making a similar mistake. Following the revolution in December 2024, some of the group’s leaders called upon Israel for support, only to realize how unpopular that made them among their Kurdish and Arab base, many of whom are overwhelmingly pious Muslims and sympathetic to the Palestinian cause.

The SDF complaining about “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide” only to rely on the biggest genocidaire in today’s Middle East—Benjamin Netanyahu’s Israel—ought to be an irony of a different magnitude.

Similarly, the group seems to have lost sight of the fact that U.S. President Donald Trump almost withdrew from Syria in October 2019, which triggered Türkiye’s “Operation Peace Spring.” With Trump establishing a positive rapport with Sharaa and seeing him and Türkiye as the best options to take on Daesh, the SDF might be badly misreading the situation.

But misunderstanding Türkiye’s capabilities and motives could end up being the SDF’s biggest miscalculation.

Starting with Ankara’s first direct intervention in Syria in 2016, “Operation Euphrates Shield,” SDF claimed that it would stop Turkish troops and its Syrian allies only to lose at each point (see “Operation Olive Branch” in 2018 and “Operation Peace Spring” in 2019). While the SDF has gained much experience since the mid-2010s, it often loses sight of the fact that it is threatening NATO’s second-largest power, one that consistently ranks among the top militaries in the world.

That is particularly odd considering that the PKK, the SDF’s “mothership,” has been completely destroyed within Türkiye and it was on its heels in northern Iraq before Ocalan’s call for disarmament.

What is even more curious about this factor is that SDF ringleaders know Türkiye and Turks quite well. Former PYD co-chair Salih Muslim studied at Istanbul Technical University and speaks fluent Turkish. Mazlum Abdi, who was Ocalan’s adopted son, is believed to have a strong command of Turkish as well, like many other Syrian Kurdish leaders—be they pro-SDF or otherwise.

But the bigger problem is political and historical, not military or linguistic.

Both the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Turkish public opinion have a hard time putting their faith in the ongoing disarmament talks with the PKK owing to how the “peace process” of the mid-2010s ended in bloodshed. In 2026, any attempt at reigniting old conflicts in Syria or within Türkiye is likely to lead to a bad situation for all parties, but especially the weaker side, which now appears to be the SDF, PYD/YPG and PKK.