Across Türkiye, a broad segment of society shares the same feeling: life has become materially harder, and the standards once considered normal for middle-income households are increasingly out of reach.

This perception is not merely anecdotal. Economic indicators show that the deterioration is deeper and more structural than most households initially assume. Income erosion, asset loss, and declining purchasing power are reshaping daily life in ways that go beyond cyclical hardship.

What is unfolding is not a temporary squeeze, but a systematic hollowing out of the middle class. The trend resembles patterns long associated with parts of Latin America, where societies polarize between a small affluent group and a large population living with persistent economic insecurity.

In technical terms, economists often define the middle class through income or consumption thresholds, such as households spending between $10 and $100 per day or earning close to the median income. These metrics offer comparability but fail to capture lived reality.

Middle-class status is ultimately defined by stability and the expectations that accompany it. It implies being able to live on a single salary, absorb unexpected expenses, and save for retirement without constant financial anxiety. It also includes access to decent housing, reliable health care, and quality education for children.

Equally important is the belief in upward mobility. The middle class is sustained by the expectation that the next generation will live better than the previous one. When this belief collapses, middle-class identity becomes symbolic rather than material.

Türkiye’s modern middle class expanded during the industrialization and urbanization waves of the 1960s and 1970s. Manufacturing growth and public sector employment created new forms of economic security for millions of households.

From the 1980s onward, neoliberal reforms weakened organized labor but initially expanded white-collar employment and service-sector jobs. This phase gave the impression of sustained middle-class growth, even as protections eroded beneath the surface.

The 2000s introduced a credit-driven growth model that masked structural weaknesses. Rising consumption was fueled less by income gains than by debt accumulation, leaving households exposed when economic conditions shifted after 2018.

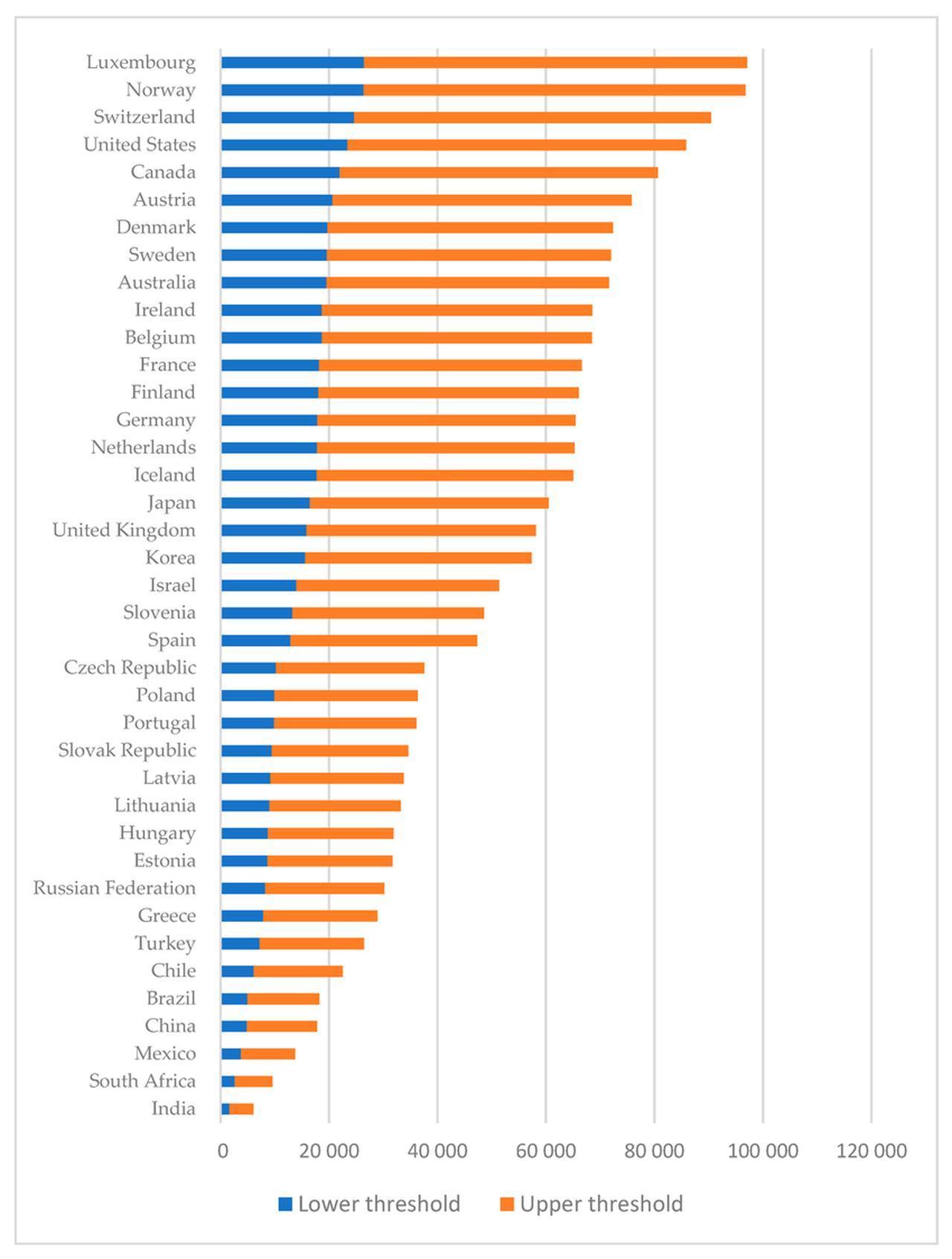

International data, including OECD assessments, place Türkiye among the countries where the middle class is shrinking at one of the fastest rates. Wealth and income are concentrating at the top, while a growing share of society slips toward precarity.

In market economies, the middle class functions as a stabilizing bridge between wealth and poverty. It underpins democratic participation, supports tax systems, and sustains social cohesion. When that bridge erodes, institutions weaken and social tensions intensify.

The absence of a strong middle class also reduces the capacity of states to pursue long-term development strategies rooted in broad-based prosperity.

Over the past years of the country, persistent inflation has become one of the most destructive forces. Acting as an invisible tax, it steadily erodes savings and wages, making long-term planning nearly impossible for households that depend on fixed or semi-fixed incomes.

The housing problem, although not special to Türkiye, has emerged as another critical pressure point. Home ownership, once a cornerstone of middle-class security, has become unattainable for many salaried workers. Rent consuming more than a third of household income has pushed millions into what analysts describe as housing poverty.

As purchasing power falls, households increasingly rely on credit cards and consumer loans to cover basic needs, including food. High interest rates then trap families in a cycle of debt, transforming short-term coping mechanisms into long-term vulnerability.

Wage dynamics have shifted sharply. In many sectors, real wages lag behind inflation for years, and the minimum wage has effectively become the average wage. This applies not only to blue-collar workers but also to university-educated white-collar professionals.

At the same time, a matter of fact that is well-known, higher education no longer guarantees middle-class status. The rapid expansion of universities has devalued degrees, while the cost of quality education continues to rise. Families invest more in schooling yet receive diminishing economic returns.

Uncertainty surrounding pensions and healthcare further weakens the middle-class safety net. When retirement and social security systems appear unstable, households are forced to rely solely on current income, increasing anxiety and reducing consumption confidence.

Despite declining living standards, many citizens continue to identify as middle class. This self-perception functions as a status marker and often delays collective recognition of the depth of the problem.

The erosion of the middle class is frequently internalized as personal failure rather than understood as systemic breakdown. This misattribution obscures the role of policy choices and weakens demands for structural reform.

Historically, when the middle class loses faith in the system, political trust erodes. Disillusionment creates fertile ground for populist movements and increases polarization, placing additional strain on democratic institutions.

Rebuilding the middle class requires more than short-term relief measures. Macroeconomic stability, particularly sustained disinflation, is a prerequisite for restoring confidence in wages and savings.

Housing policy stands out as a central lever. Treating housing as a social good through public investment, rent regulation, and affordable supply could re-anchor middle-income households in urban life.

Tax reform that reduces the burden on labor while addressing wealth and capital income is another critical step. Without such redistribution, income polarization is likely to deepen further.

The erosion of Türkiye’s middle class is not the result of an unavoidable global trend. It more likely reflects a sequence of economic models and policy decisions that prioritized short-term growth over long-term resilience in the last decade.

The issue, at its core, is not about nostalgia for the past but about whether a broad segment of society can once again plan for the future with confidence.

Whether this trajectory continues or reverses will shape the country’s politics, sociology, and the fate of the country for decades. However, as seen in many countries, a stable, confident middle class remains one of the strongest foundations for economic development and democratic stability of a nation.