This article was originally written for Türkiye Today’s weekly newsletter, Levant Archaeology Digest, in its Feb. 11, 2026, issue. Please make sure you subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here.

The world’s oldest ritual area is going on tour. This week, the mysteries of Gobeklitepe are taking center stage, leaving the dusty plateaus of Sanliurfa for the spotlight in Berlin.

A new major exhibition, “Building Community: Gobeklitepe, Tas Tepeler and Life 12,000 Years Ago,” has opened its doors in the German capital, bringing original artifacts from Türkiye into one of Europe’s most symbolic museum landscapes.

After the Colosseum’s blockbuster Gobeklitepe show in Rome, an event that successfully turned a Neolithic sanctuary into a global public narrative, Berlin now becomes the second major European stage in this cycle of archaeological diplomacy.

This matters for more than visibility. When early ritual architecture is translated into a museum exhibition, something subtle happens: the site is no longer only a place. It becomes a portable argument, an argument about how communities form, how symbolism stabilizes identity, and how “the first monuments” can be framed for the modern public.

Berlin’s show isn’t about rock and bones. It’s about human history. How humans built communities, lived, loved, and tried to find meaning all those thousands of years ago.

Archeologists aren’t really debating the real part of this outreach; that part is given.

The real question is what version of Gobeklitepe is being shown to the world. Is it a sacred sanctuary? A “zero point” of history? Or is it a crown jewel of the broader Tas Tepeler region, which is now being pitched as our best window into how ancient society began?

I’m Koray Erdogan, an archaeologist with seven years of fieldwork experience across Anatolia’s layered past. I currently serve as assistant director of a Mediterranean surface survey and contribute to digital archaeology initiatives. Together with the Türkiye Today team, we are committed to bringing you trusted reporting and deeper insight into the region’s heritage.

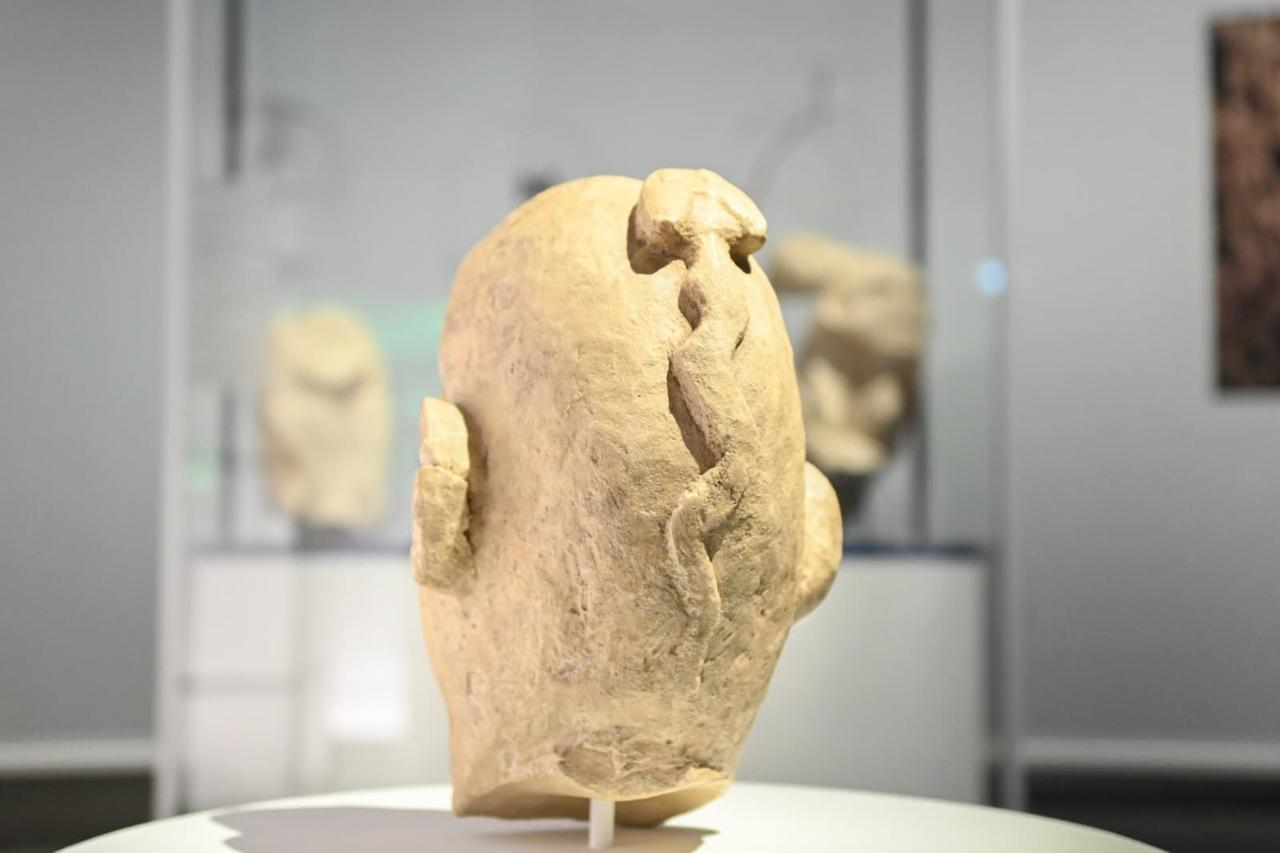

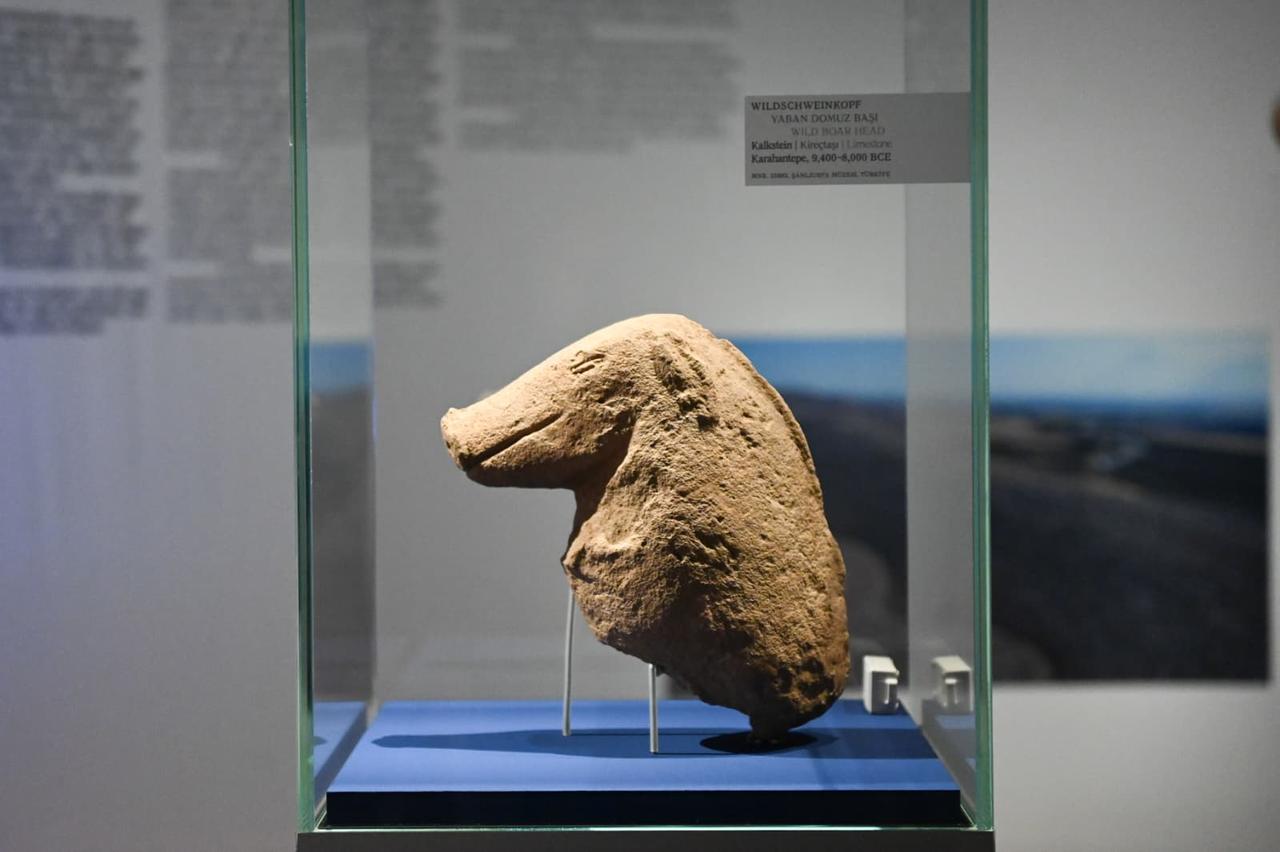

The Berlin exhibition presents 93 selected artifacts tied to Gobeklitepe and the wider Tas Tepeler region, organized through eight thematic sections that trace lived experience, from birth and daily routines to death and remembrance. It runs Feb. 6 to July 19, 2026, hosted by the Museum of the Ancient Near East on Museum Island.

What gives the Berlin edition particular weight is the institutional architecture behind it: Cooperation between Türkiye’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums, and the Istanbul branch of the German Archaeological Institute.

Tas Tepeler coordinator Professor Necmi Karul frames the exhibition as the latest expression of more than a century of Turkish-German archaeological cooperation, while also emphasizing a newer point: Gobeklitepe is not an isolated “miracle site,” but part of a regional network—a research landscape with multiple active excavations and multinational teams.

A parallel thread that is both visual and strategic.

Spanish photographer Isabel Munoz’s Gobeklitepe images are now part of the Berlin presentation, reinforcing a trend that has been accelerating in heritage outreach. The use of contemporary art photography to create emotional proximity to deep time. In this edition, the exhibition combines archaeological material from the Sanliurfa Museum collection with Munoz’s photographs, aiming to tell a 12,000-year-old story with both anthropological and aesthetic tools.

The Berlin edition also draws a quiet line across institutions and borders: Munoz’s work was first shown in Istanbul at the Pera Museum (2023), later travelling to Ankara, and then Spain (2024). Now it enters a major European museum setting, functioning almost like an interpretive bridge between field archaeology and public imagination.

For academics, this raises a productive question: What do photographs “do” to prehistoric monuments that already function as images? Are we documenting material, or producing a new layer of aura?

Berlin’s show is part of a broader shift in how early Neolithic research enters public discourse.

From excavation reports to a cultural narrative: “Community-building” becomes the interpretive headline.

From site to landscape: Tas Tepeler frames Gobeklitepe as one node among many.

From national heritage to international stage: Original objects traveling abroad reconfigure scholarly and ethical conversations about stewardship, access, and representation.

From archaeology to diplomacy, cultural ministers attending openings is not decoration—it signals archaeology’s role in contemporary soft power.

There is also a methodological side: Large exhibitions increasingly influence what the public (and sometimes even policymakers) believe archaeology has “proven.” That makes curatorial framing part of the discipline’s public interface.

Ritual-first, community-first, or art-first?

Berlin’s framing, “Building Community: Gobeklitepe, Tas Tepeler and Life 12,000 Years Ago,” signals clearly that it is community-first.

The ritual dimension is present, of course; Gobeklitepe cannot escape its monumental enclosures and T-shaped pillars. But the curatorial language shifts the emphasis from “the first ritual area” to “the first communities.” That is a meaningful pivot.

This is not a sanctuary isolated in sacred exception. It is presented as part of a lived world:

Daily practices,

material production,

social organization,

birth and death.

Art is not foregrounded as autonomous aesthetic production. Instead, sculpture and carving are framed as expressions of social cohesion. In that sense, Berlin is quietly updating the older “ritual center built by hunter-gatherers” narrative toward something more structurally complex: Monumentality as a product of emerging community formation.

The thesis is closer to: Symbolic systems stabilizing early communities.

This is perhaps the most important intellectual move.

For over a decade, Gobeklitepe functioned as an anomaly. A singularity. A headline.

The Tas Tepeler project has fundamentally changed that perception. Berlin’s emphasis on a broader landscape—around 30 related sites—helps dismantle the “miracle site” narrative.

But there is a delicate balance:

If Gobeklitepe remains too central, Tas Tepeler becomes a footnote.

If Tas Tepeler dominates too strongly, Gobeklitepe loses the monumental clarity that made it globally legible.

Berlin seems to attempt a recalibration rather than a displacement. Gobeklitepe remains the anchor, but it is no longer alone.

That is not dilution.

It is contextualization.

For researchers, this is critical. The Neolithic is not a point on the map; it is a network.