The recent proposal by former U.S. President Donald Trump to introduce 50-year mortgages reignited global discussions about long-term affordability.

Across the world, housing affordability has become a defining social and political issue. From the Netherlands’ D66 victory to Zohran Mamdani’s campaign in New York, parties that propose convincing housing solutions are gaining traction.

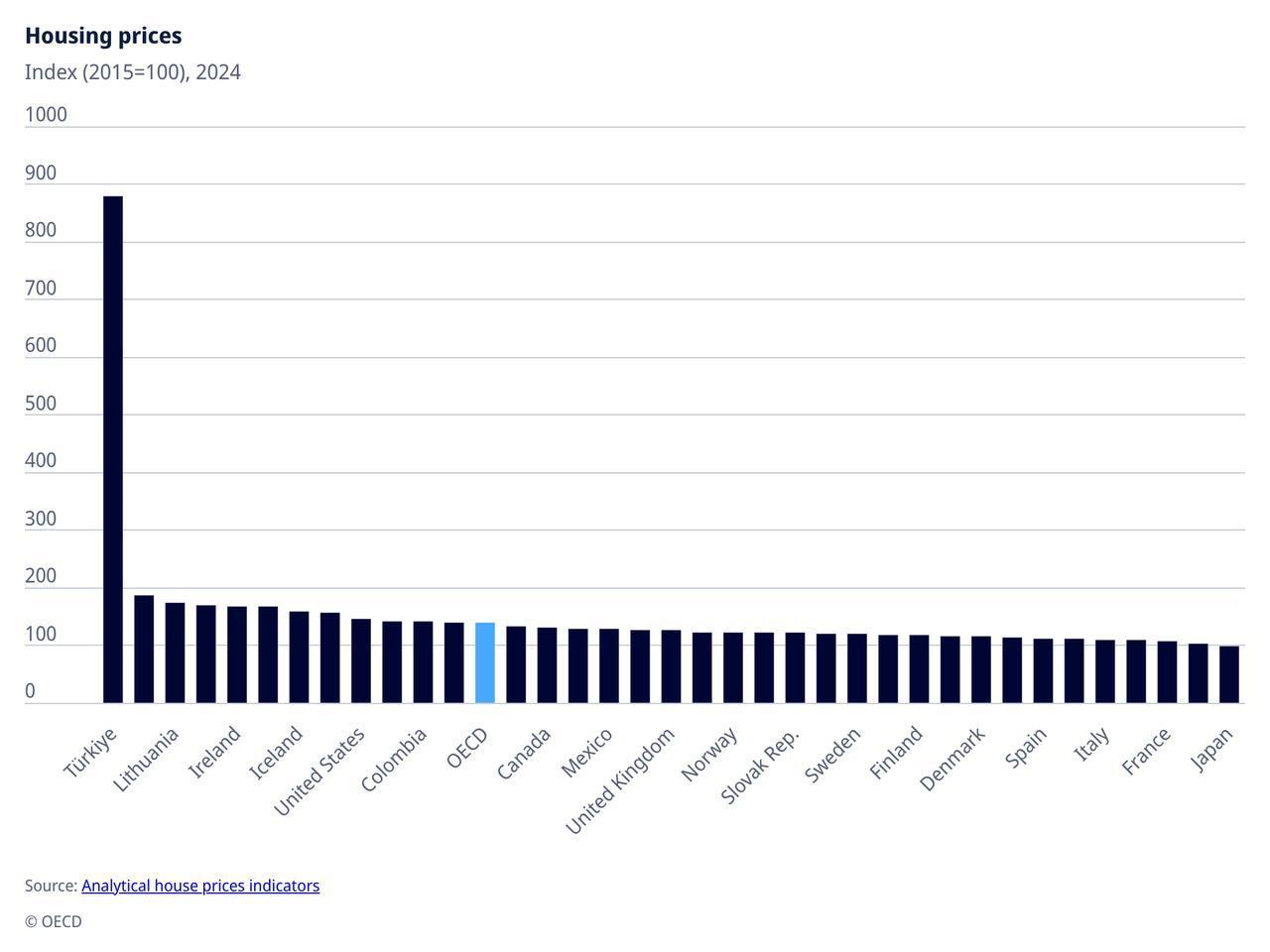

The problem has become almost a global crisis—yet in Türkiye, where the issue arguably affects everyday life more deeply than anywhere else, it remains overshadowed by other political polemics.

However, for Türkiye, the debate extends far beyond financing mechanisms—it is about survival in cities where even the upper middle class is now priced out of both renting and owning homes.

Recently, the government announced a project to build 500,000 affordable housing units for young people and considered the build-operate-transfer model on state-owned land to boost supply, but none of the options offer a real solution.

Türkiye’s housing crisis is no longer a topic of academic debate—it has become a daily reality for millions. Even top executives are not immune. The general manager of Is Bank, one of the country’s largest financial institutions, recently revealed that he had to leave his apartment after his rent jump.

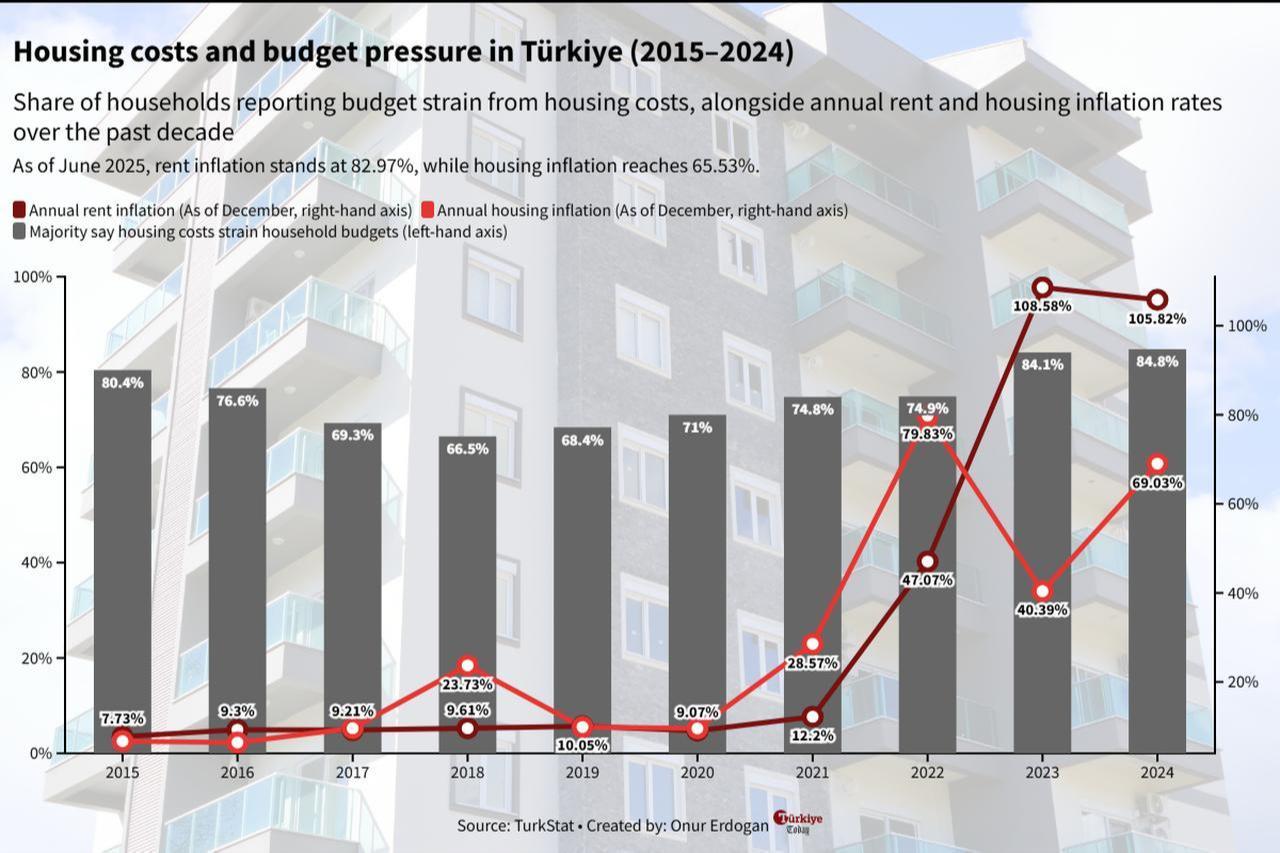

Economic policymakers, including Treasury and Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek, have acknowledged that rent hikes are now one of the most significant contributors to inflation. Yet despite efforts to curb inflation, rental prices continue to spiral, making it impossible for courts to handle the growing number of landlord-tenant disputes.

International benchmarks suggest that rent should not exceed 30% of household income. In Türkiye, that ratio has long collapsed.

Over the recent years, while official inflation data shows wage increases of 20%–30%, rent inflation exceeds 65%, meaning each year, families grow poorer in real terms.

Many now spend up to 70% of their income just to stay in rented housing. This imbalance deepens economic anxiety, forcing families to sacrifice savings and quality of life.

Buying a home is no better. Even assuming access to a mortgage—a challenge in itself—monthly payments can exceed a whole salary, and the total repayment after 10 years can surpass ₺11 million ($260,361).

Bank credit restrictions, high interest rates, and rising construction costs have created an environment where renting is unsustainable and buying is impossible.

Unlike the U.S., mortgages over 15 years don’t exist in Türkiye.

Recent data show why producing more housing is not the answer, as the wealth inequality is mirrored in property ownership.

The wealthiest 20% of the population now accounts for over half of the increase in homeownership over the past few years, while ownership among middle- and low-income groups has stagnated or declined.

This concentration of property in the hands of a few has created a feedback loop that inflates prices and keeps younger generations locked out of the market.

According to official data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat), housing sales have outpaced household growth, yet the share of families living in their own homes has declined. In contrast, the number of renters has sharply increased. This points to an unsettling reality: those who already own property are buying more, while new buyers are being pushed out of the market.

The transformation of housing into an investment vehicle is also visible in the number of vacant properties. Research by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality estimates that between 450,000 and 700,000 homes in Istanbul stand empty, most of them high-end properties serving as second or third homes for the wealthy.

Other countries facing similar crises have experimented with bold policy interventions. Spain, for example, introduced extra property taxes on multiple-home owners who keep properties vacant. In some regions, the state even reserves the right to lease unused properties directly. These measures aim to discourage speculative behavior and increase housing supply.

Türkiye could adapt similar models. Establishing a nationwide real estate data system to track market prices and rent averages would help counter manipulation by listing platforms and improve transparency. Moreover, stricter enforcement of listing regulations could prevent speculative inflation of rental and sales prices.

The country’s main public housing agency, TOKI, was originally designed to provide affordable housing but has drifted toward building luxury units that remain out of reach for most citizens.

In Istanbul, the Housing Development Administration (TOKI) has completed roughly 51,000 units, but only 678 of them were designated for low-income families.

To rebalance this, Türkiye needs a new wave of social housing projects tailored for lower-income households. These projects should include preferential loan rates, subsidies, and, in some cases, direct financial aid for renters.

Rent assistance programs, as common in Europe, should also be considered. Targeted support for low-income families can prevent homelessness and reduce the pressure on urban centers. However, such programs must be tightly regulated to prevent misuse and ensure that benefits reach those genuinely in need.

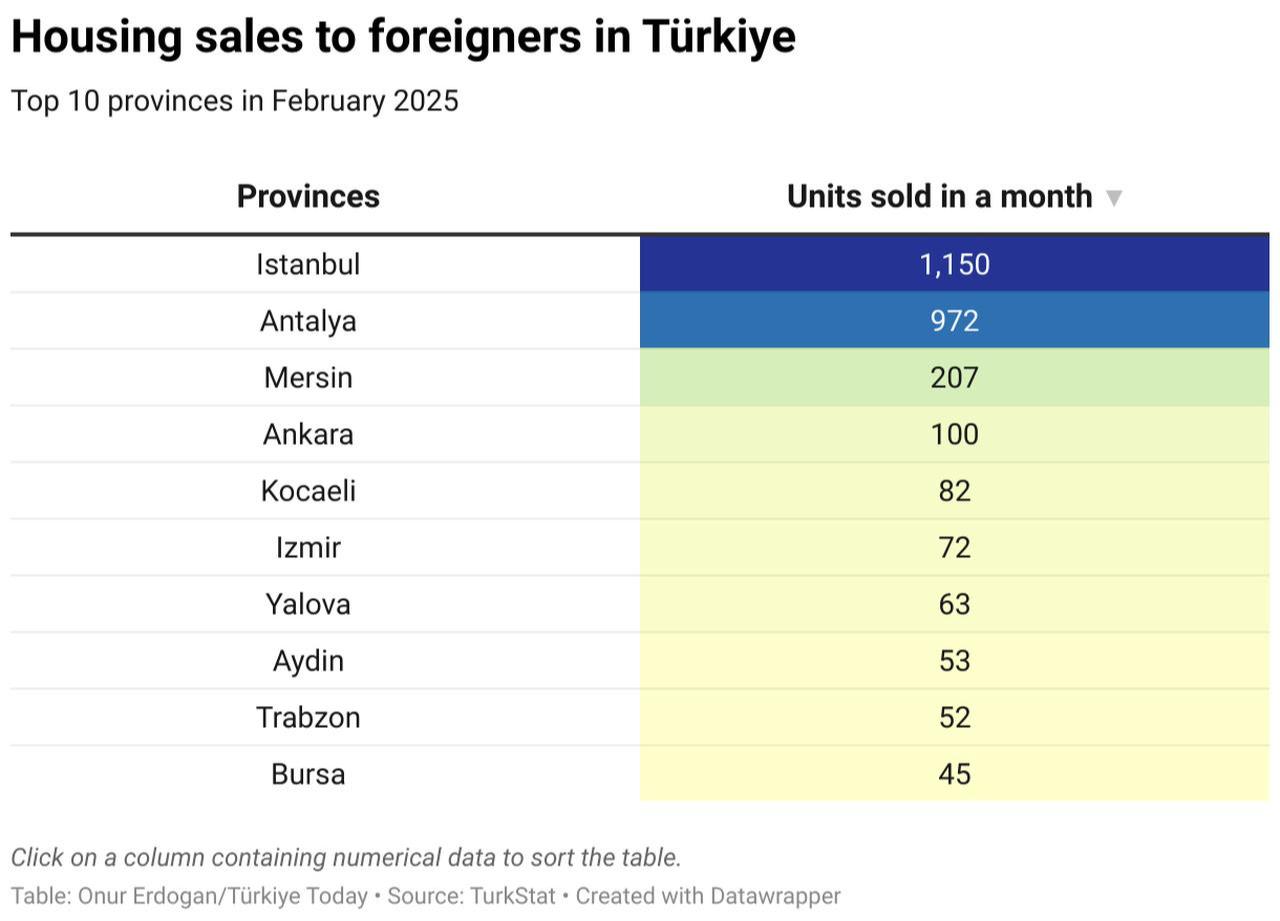

The sale of Turkish property to foreign nationals has also affected domestic affordability. Under the current system, foreign buyers can obtain citizenship by purchasing property worth at least $400,000. This policy, while intended to attract investment, has instead inflated prices in major cities and created speculative bubbles.

Unlike Türkiye, countries with similar programs, such as Greece and Portugal, apply strict geographic and price-based limits on foreign property purchases.

Türkiye could follow suit by introducing tighter restrictions on high-demand urban areas, higher thresholds for investment-based citizenship, or the removal of automatic citizenship rights altogether. Housing becoming a shortcut to nationality is not good, neither for the housing crisis nor for the citizens rights.

Cooperative housing presents another underutilized opportunity. Türkiye has a legal framework for housing cooperatives that offers tax advantages, but poor oversight has led to inefficiency and public distrust. Reviving this model—through transparent governance, public land allocations, and restrictions on resale—could provide sustainable, community-driven housing alternatives.

For many Turkish families, the inability to buy a home has become not just an economic issue, but an emotional one. Parents worry they cannot leave anything to their children; renters live under constant threat of eviction or steep rent hikes. The social pressure to own a home remains strong, yet the financial means to do so have evaporated.

The housing market’s transformation is not an isolated phenomenon but part of the country’s broader economic imbalance. As traditional forms of income generation, such as small business or wage labor, fail to provide stability, property becomes the only perceived refuge for capital preservation. This, in turn, fuels speculative cycles that lock out the very citizens the market was meant to serve.

Unless the government implements progressive taxation, enforces property-use regulations, and reintroduces social housing policies targeting low- and middle-income families, the divide between homeowners and renters will seemingly widen further, and the wider economic polarization is, the bigger sense of social despair, which is a sentiment now quietly shaping the nation’s urban and political landscape.