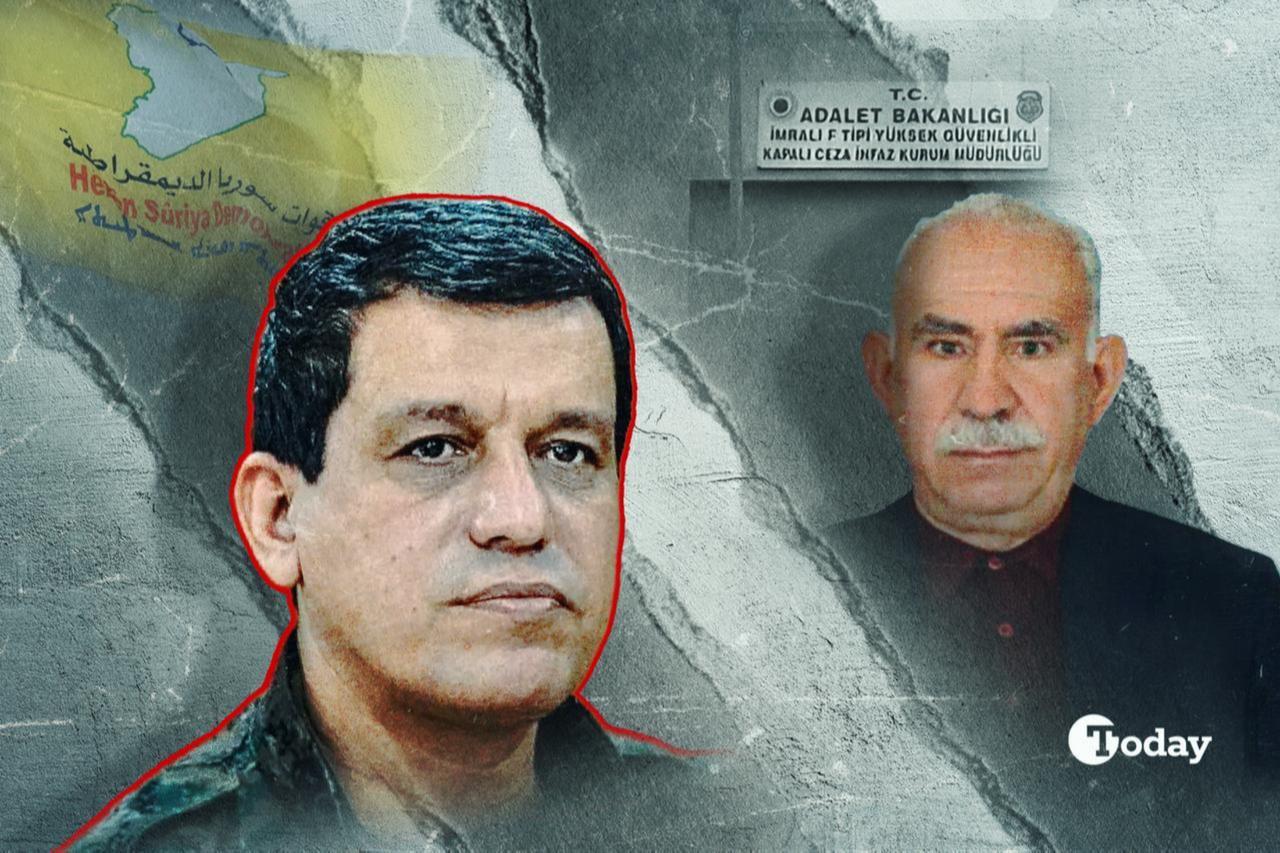

Mazloum Abdi, also known by his organizational name Sahin Cilo as a senior member of the PKK terrorist group, is neither a fully conventional head of an armed organization nor a wholly modern political actor. He is neither a pure bearer of PKK ringleader Abdullah Ocalan’s ideological legacy nor a representative of the "pragmatic politicians" aligned with the Barzani line. Rather, caught between history, geography, and organizational identity, he embodies a new psychopolitical category that can be termed a "hybrid" terrorist leader.

Abdi ordered dozens of attacks in Türkiye against Turkish security forces. After Assad’s fall, Abdi aims to position himself as a legitimate figure representing the Kurdish minority in Syria, and hopes that Türkiye’s internal peace process will wipe out Türkiye’s security concerns against his armed group SDF.

He aims to get the same political transformation as Ahmed al-Sharaa, who was once leading an insurgent group and became Syria’s legitimate president. However, he did not fight the regime to claim Sharaa’s prize, and his game of stalling the unification of Syria will not ease Türkiye’s security concerns due to the latter's internal peace process. Türkiye has leverage to run an internal peace process while running an operation against the SDF due to security concerns. Yet, Abdi thinks otherwise.

This analysis offers an in-depth exploration of Abdi, spanning his personal character, organizational behavior, psychological reflexes, and the potential for integration into Syria.

The “hybrid leader prototype” refers to a specific type of leader who emerges during moments of political and organizational transformation. These leaders are caught between the rigid shell of revolutionary ideology and the cold realities of realpolitik.

On one hand, they cannot entirely sever ties with the mystical authorities of the old order; on the other, they are compelled to make pragmatic adjustments in response to the demands of the international system. Abdi exemplifies this dynamic. While demonstrating emotional loyalty to Ocalan’s charismatic-shadow authority resembling a dictator, he also shows a tendency to gravitate toward the more flexible approach associated with the Barzani line.

A hybrid leader is both symbolic and operational but can never fully assume the role of the primary charismatic figure. Such leaders typically follow the path laid by the “ideological father” while making strategic adaptations to sustain the movement. Psychologically, they oscillate between dependency and autonomy, resulting in continuous internal tension and identity flux. Abdi’s voice, demeanor, and statements, together with his measured approach to organizational relationships, reflect this internal conflict outwardly.

The most accurate way to understand Abdi’s personality is through the archetypal shadow of PKK’s ringleader Ocalan. The Ocalan archetype represents absolute authority within the organization; he is not only a political leader but also a “father figure” occupying the psychological center. His presence channels the emotional and cognitive orientation of all organizational actors.

Abdi operates as a “second-generation leader” under this shadow. What distinguishes him is that he does not attempt to imitate Ocalan’s charisma. The tonal contrast between Ocalan’s emotional revolutionary intensity and Abdi’s measured diplomacy is the clearest marker of the hybrid leader prototype: a continuation of a cult leader’s legacy, but not a replica; a sustainer of revolutionary discourse, yet with a moderated rhetoric.

Abdi’s rapprochement with the Barzani line can be interpreted as an internal psychopolitical shift within the organization. Historically, the PKK and Barzani have maintained a competitive relationship. From Turkish analyst Yalcin Kucuk’s perspective, the PKK functions as a buffer against “Barzanization,” strategically keeping Kurds in Türkiye distant from Barzani-style nationalist politics. The ideological line represented by the PKK and the Kurdish nationalist line represented by Barzani have long been in competition. Abdi’s engagement in Duhok and calls for unity can be read as steps toward distancing himself from Ocalan’s cultic leadership and moving closer to the Barzani line. This shift increases both ideological flexibility and field effectiveness while generating tensions that challenge Ocalan’s central authority.

While Ocalan attempts to balance Iranian and Israeli influences over the organization, Abdi’s field practices and leadership simultaneously constrain internal Barzani-leaning tendencies. This illustrates the hybrid leader’s psychopolitical role as a decisive factor in shaping the organization’s future trajectory.

Abdi’s alignment with the Barzani line is not merely a pragmatic strategy; it is also a natural outcome of the psychopolitical need for autonomy, arising from Ocalan’s imprisonment due to 40-year old terror activities and the movement’s cautious stance toward Kurdish nationalism. Türkiye’s tight control limits the maneuvering space for PKK ringleaders, compelling Abdi to establish his autonomous path and preserve strategic initiative within the organization. This process has been restricting the operational flexibility of Ocalan’s ideological shadow and diminishing the impact of his authority in the field.

Moving toward the Barzani line does not only mean adopting the KDP’s pragmatic, state-oriented politics; it also ties directly to Israel’s use of Barzani/Kurdish nationalist structures as strategic levers in the region. Israel has historically engaged Kurdish actors through this line to maintain regional balance, deeply influencing the organizational evolution and ideological formatting of the YPG.

Abdi’s approach reflects a tendency to loosen classical PKK ideological constraints, introducing a flexible ideological cover. This reframing emphasizes Kurdish nationalism as a motivational force and accepts discreet engagement with Israel. Ocalan’s statement that the SDF is under Israeli influence, while Kandil aligns with Iran, highlights the fault lines in PKK geopolitics. Organizational discipline and field operations increasingly operate under Abdi’s pragmatically calculated relationships with the U.S. and Israel, rather than being strictly dictated by the Ocalan archetype. This model functions both to safeguard organizational security and to secure advantages in regional actor relations.

Even though Ocalan maintains symbolic authority, this authority has weakened in the field due to pragmatic necessities and ideological reframing. Abdi’s orientation toward the Barzani line generates a psychopolitical balance that simultaneously constrains Ocalan’s central authority and enhances the organization’s strategic autonomy. In sum, ideological reframing and field pragmatism emerge as the main factors reshaping both leadership capacity and power dynamics within the organization.

Abdi’s strategy toward the Syrian regime can be described as “proximate but cautious.” The regime still perceives him as a potential threat due to his ties with the U.S. and Israel, and its centralizing reflexes and control imperatives continuously constrain his maneuvering space. Abdi, however, understands that the regime’s bureaucratic rigidity offers limited flexibility for his strategic objectives. Consequently, he acts cautiously, avoiding abrupt or radical integration moves.

Full integration would diminish his limited but critical influence with Washington, weaken organizational autonomy, and reduce strategic maneuverability. Hence, Abdi prefers a semi-autonomous relationship with the regime, based on temporary alignments of interest. This approach allows him to maintain organizational independence while pragmatically balancing relations with Damascus.

He also relies on Türkiye’s domestic peace process. He bets that Türkiye would not attack SDF forces during the peace process, as such an operation would create unease in Türkiye’s Kurdish political circles, which would eventually derail the process. However, such a bet is risky, and could result in a renewed Turkish operation in Syria, as Türkiye is getting frustrated with SDF’s stalling, as for Türkiye, it means SDF’s real target is to declare statehood in the long-run.

Abdi’s engagement with Israel is calibrated on a delicate balance of regional power dynamics and threat perception. Excessive closeness would provoke deterrence by Iran and Syria, while total disengagement would weaken security partnerships with the U.S. and the West. Therefore, he pursues cautious, discreet, and controlled rapprochement.

This balance parallels Ocalan’s observation of Israel’s long-term influence over the SDF. Abdi’s subtle and cautious diplomacy acknowledges Israel’s strategic leverage while maintaining alliances with Western powers. High-profile statements are replaced by behind-the-scenes engagement—“low-noise diplomacy”—which preserves field autonomy and maintains security guarantees. Controlled cooperation, rather than overt hostility, enables Abdi to navigate both Iranian and Syrian pressures while securing Western support.

All these factors combined suggest that Mazloum Abdi’s future depends on the interplay of regional pressures, organizational constraints, and international dynamics. His leadership is not revolutionary in the sense of producing dramatic upheaval; rather, as a hybrid leader of a terrorist organization, he focuses on maintaining stability, preserving organizational autonomy, and delaying potential collapse.

This is the defining trait of the hybrid leader prototype: not a figure who shapes history dramatically, but one who is carried along within the historical currents, managing survival and continuity in a highly complex and dangerous environment.