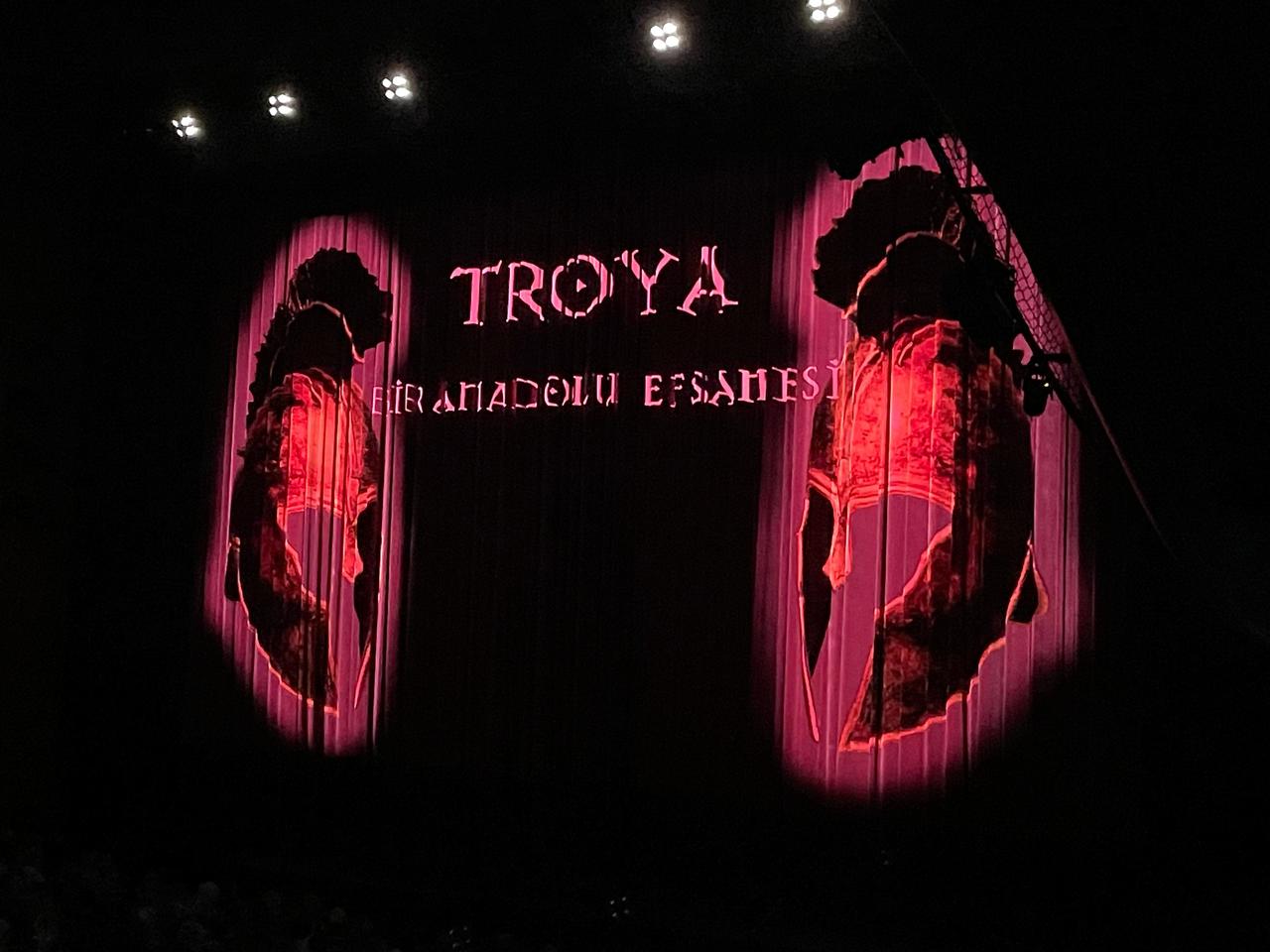

On Tuesday evening, Feb. 10, 2026, at Istanbul’s Ataturk Cultural Center, Fire of Anatolia, a Turkish dance group led artistically by Mustafa Erdogan, brought its long-running “Troy” production back into focus with a clear thesis: “Troy is Anatolia,” paired with the assertion that Homer was from Smyrna, today Izmir. Rather than treating the Trojan story as a distant Mediterranean myth, the performance positioned it as a narrative rooted in western Anatolia, and it carried that framing from the opening beats through to a finale built around peace messages.

Unlike many films and theater adaptations, the costumes and set design avoided a generic Greek visual vocabulary and instead presented Troy and the Trojans as a wealthy Bronze Age Anatolian kingdom, an approach that shaped how the story read onstage and how the characters moved through its key turning points.

International readers may know the Trojan War through familiar headline elements: the city of Troy, the wooden horse, Helen, and a long siege. The performance kept those anchors in place, while expanding the focus to show how the epic holds more than a single plot twist.

The story, described as traveling for roughly 3,000 years through storytellers before being put into words by Homer around the 7th to 8th century B.C., later took on lasting visual power through Greek and Roman artists, and it still draws attention today because it compresses love and loss, courage and desire, violence and revenge, victory and tragedy into one enduring narrative.

The plot unfolded through the familiar chain of events: Trojan prince Paris visits Sparta on a state trip, then exceeds limits and leaves with Queen Helen, the wife of King Menelaus. Seeking to bring Helen back and repair damaged honor, Menelaus gathers a huge army of Greek heroes led by his brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae.

The army sails to Troy, sets up camp, and places the city under siege, yet Troy’s walls hold, and the Trojans defend their home with determination across years of fighting. Raids on nearby Trojan cities and the capture of residents follow, including Briseis, a young woman given to Achilles as an honor prize.

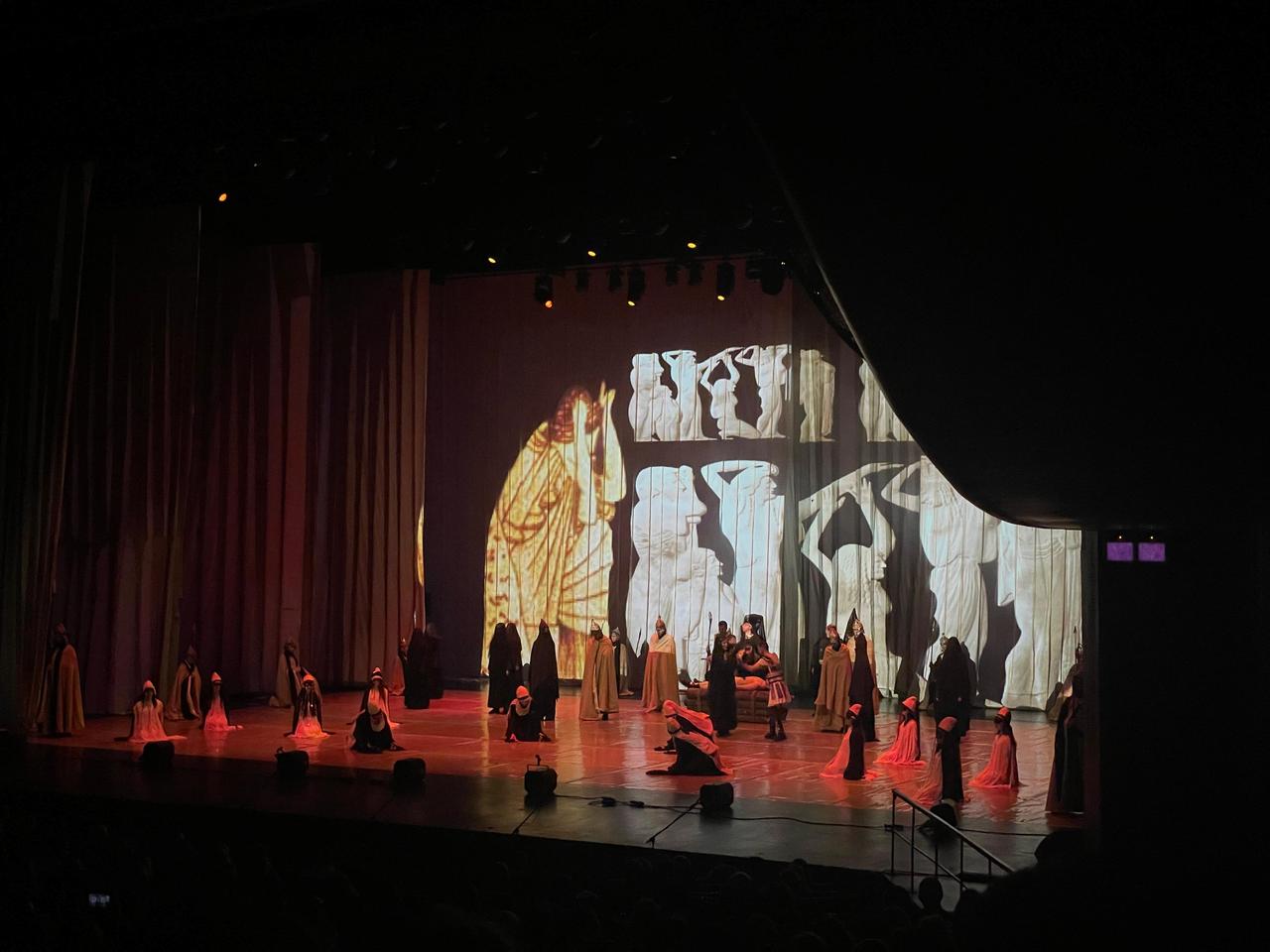

As the dance continued, visuals related to the narrative played behind the performers. One example cited during the show was a black-figure amphora dated to around 530 BCE, depicting Achilles killing Penthesilea, the Amazon queen who fights on the Trojan side, while onstage, Anatolia’s warrior women appeared in choreography aligned with that moment.

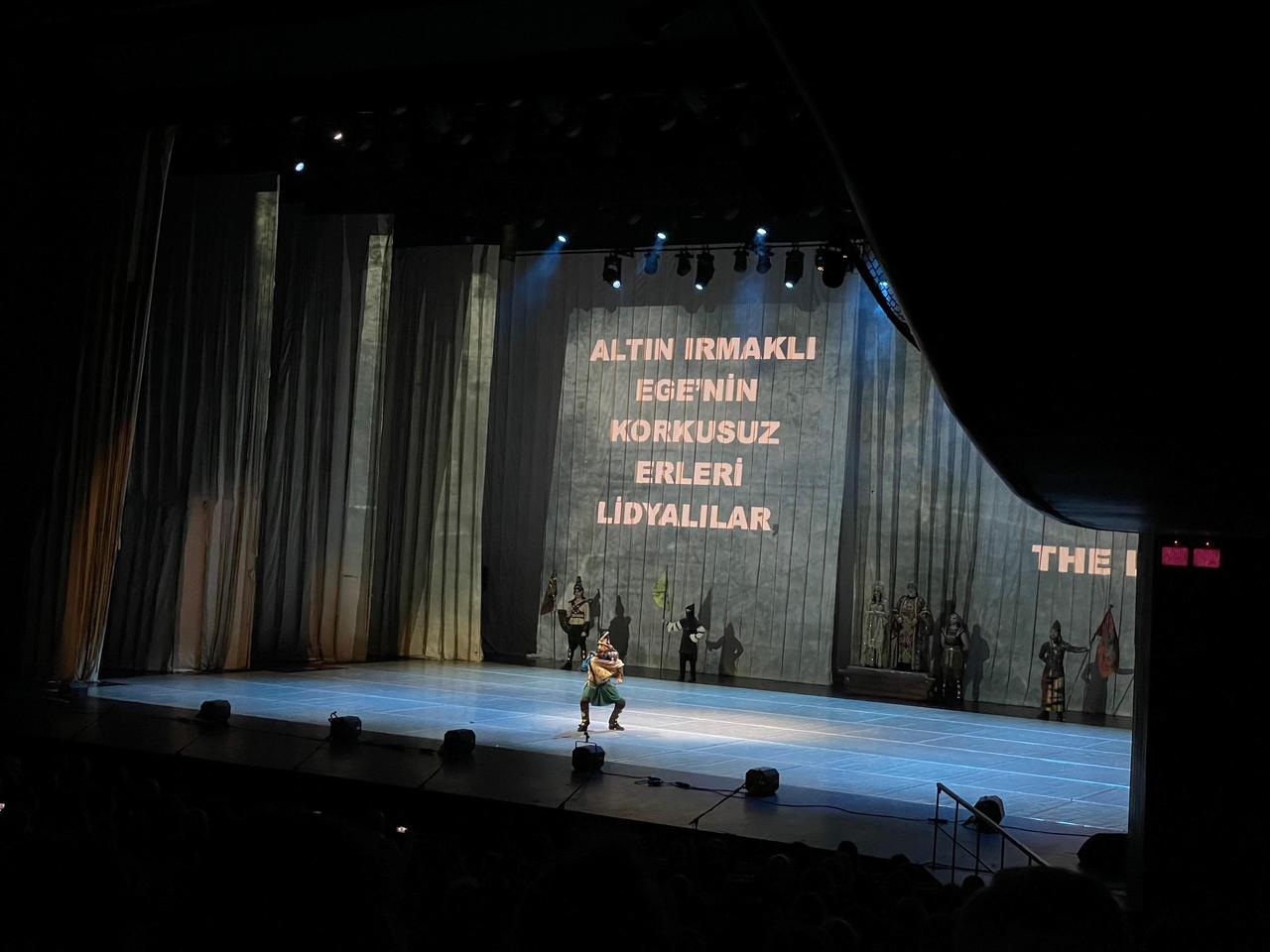

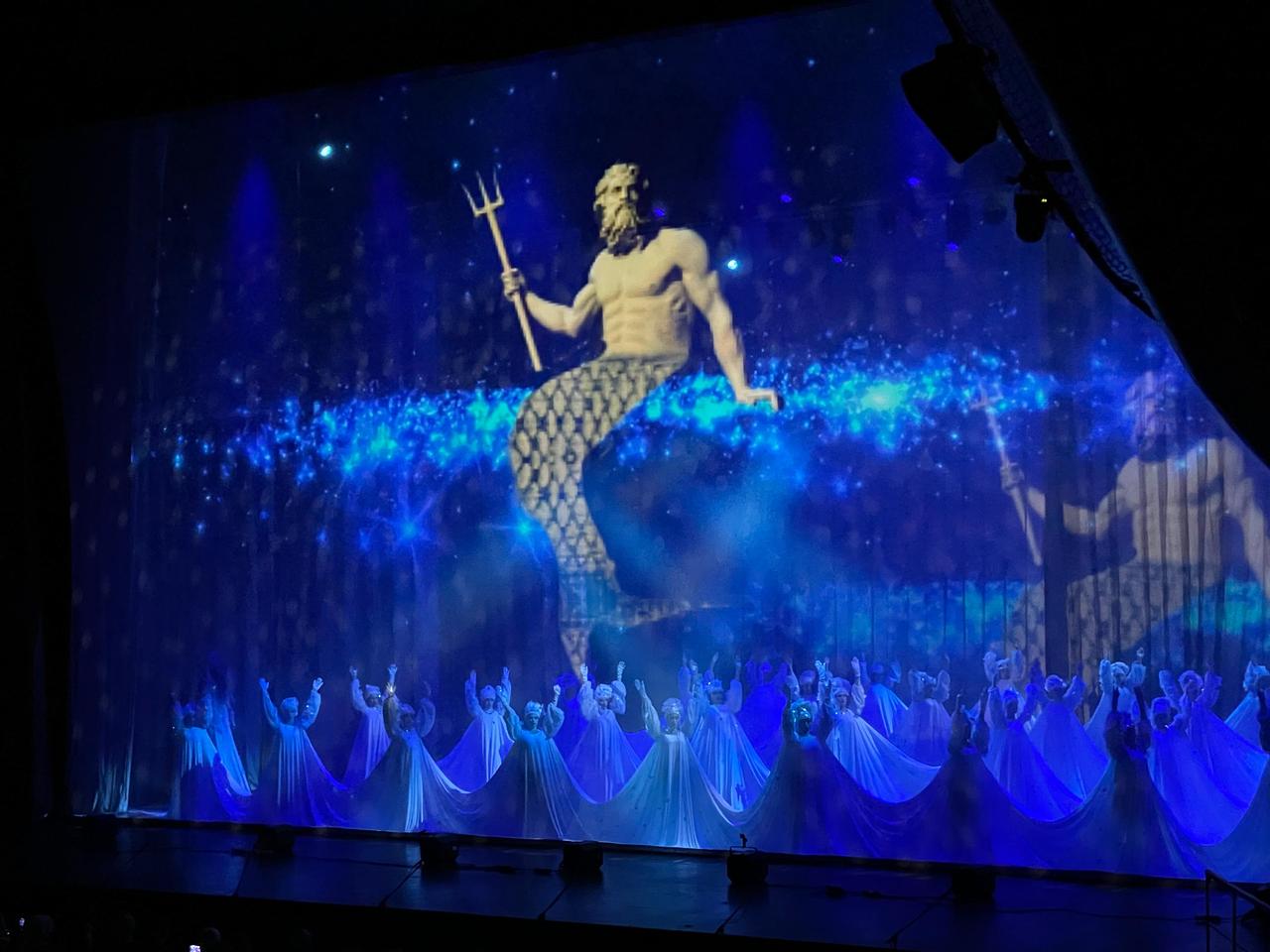

The production also brought in the idea of multiple groups fighting against the Achaeans, presenting a sequence of allies arriving to support Troy and, with each entrance, revealing a broader “dance mosaic” of Anatolia. The staging referenced assistance from the Hittites to Wilusa/Troy, Pelasgians coming from the nearby city of Larissa, and other communities said to have come from Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

Set to present-day melodies and dances, the effect aimed to merge modern Anatolia’s cultural texture with an imagined ancient world, culminating in the onstage message that “all Anatolia” stood with Troy.

Performers march in formation as projected narration references Anatolian allies in the Trojan War during Fire of Anatolia’s “Troy” performance at Ataturk Cultural Center in Istanbul, Türkiye, Feb. 10, 2026. (Video by Koray Erdogan/Türkiye Today)

In the war’s tenth year, the show moved into the dramatic episodes associated with Homer’s Iliad, and it mirrored key scenes through dance. When the Achaeans were onstage, Greek tunes and sirtaki dance appeared as part of the staging language.

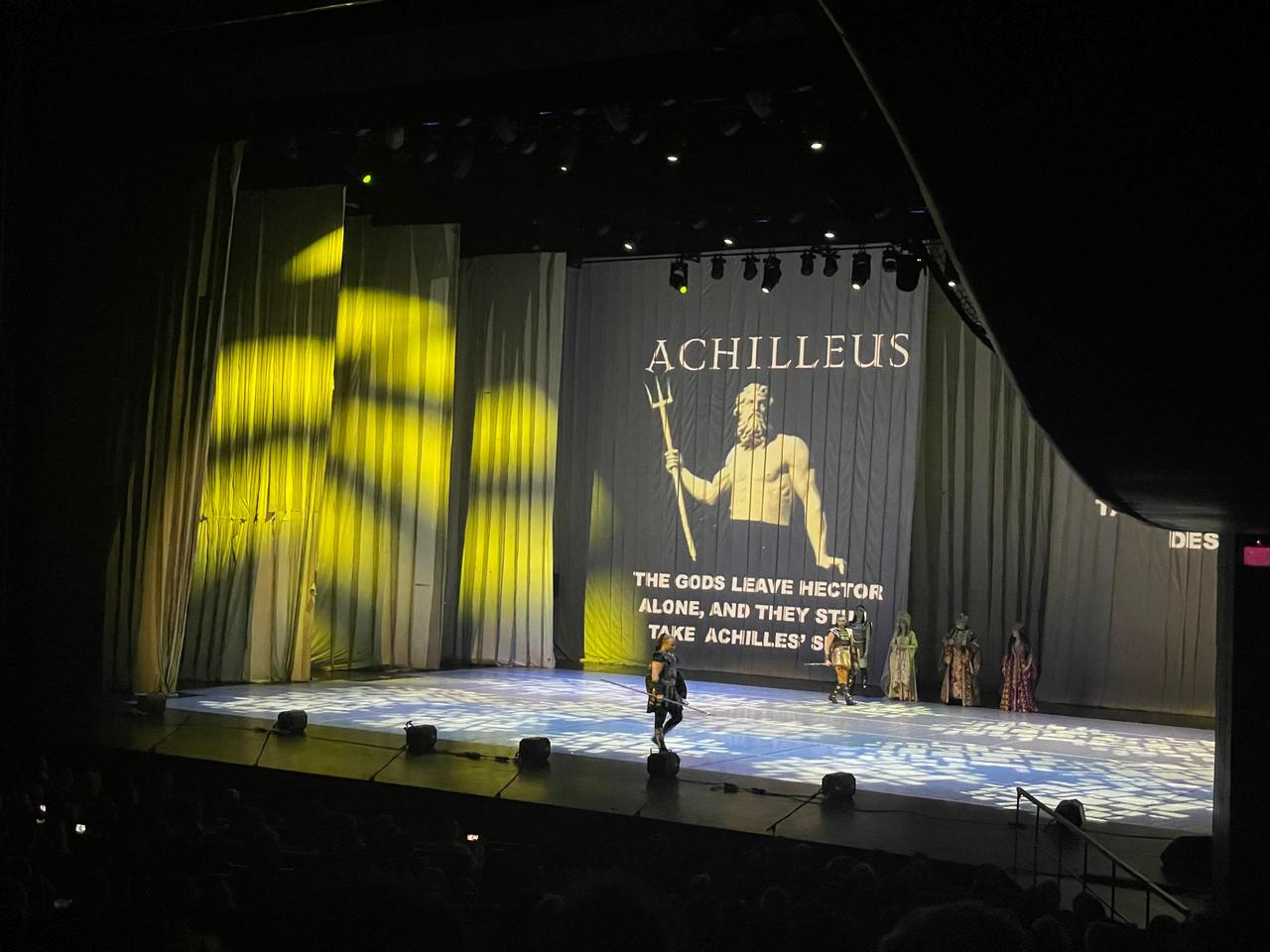

The plot then tightened around Patroclus, described as Achilles’ cousin or possibly his close friend, who wears Achilles’ likeness to raise Greek morale and intimidate the Trojans, only to be killed by Trojan prince Hector. Grief turns into rage, Achilles returns to battle, kills Hector, and takes his revenge, which the performance presented beat by beat through choreography.

Because Achilles is consumed by anger, he refuses to return Hector’s body for traditional burial rites until Troy’s aged King Priam secretly enters the Greek camp and begs for his son’s body in exchange for ransom. Achilles’ desire for vengeance eases, he accepts Priam’s plea, and Hector’s funeral becomes possible.

The staging described the ceremony as strikingly lifelike, with Hector laid on wood, surrounded by mourning music and lament dances by his mother and wife, matching the point where the Iliad ends.

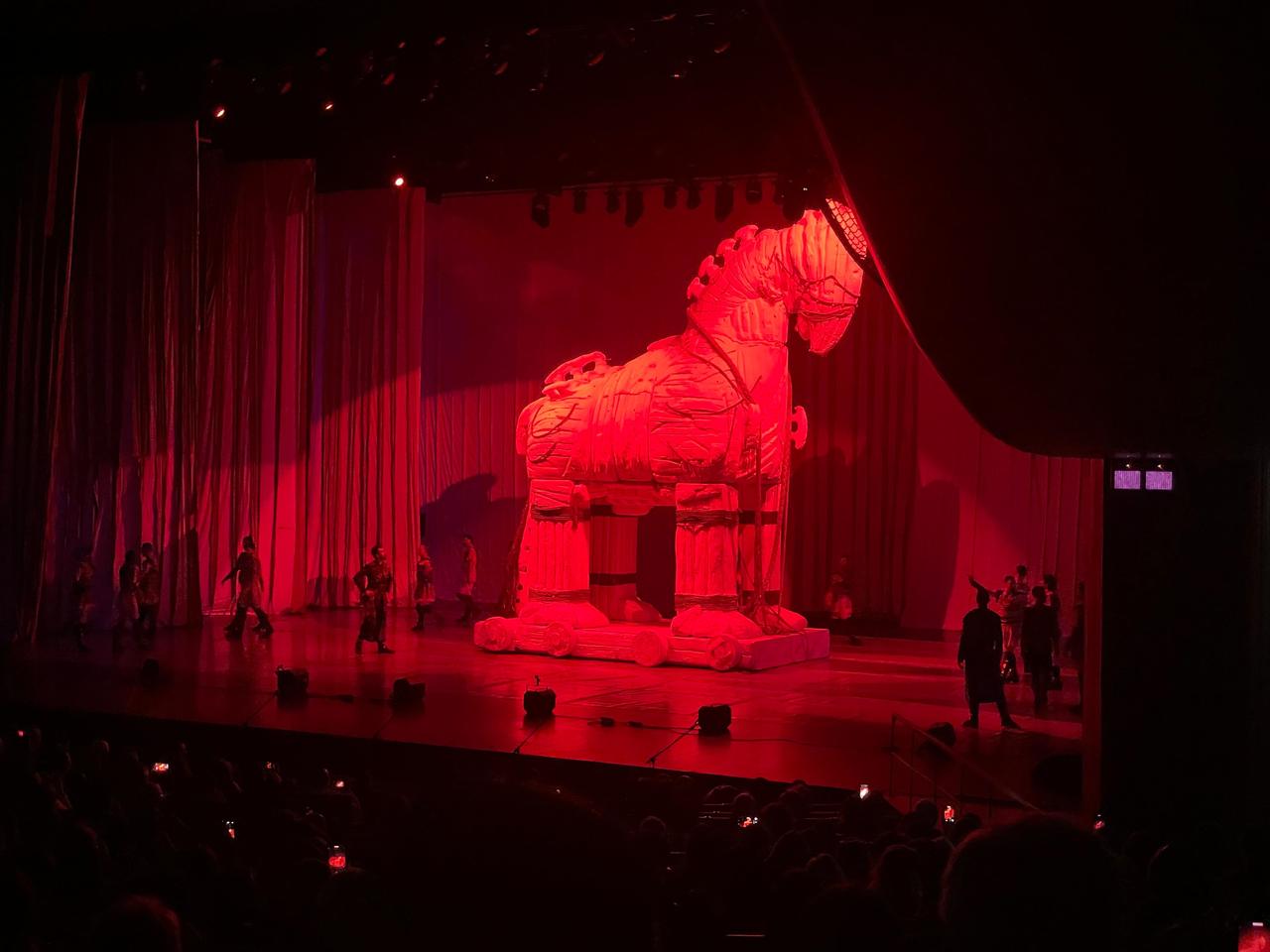

The war’s end turns on a scheme credited to Odysseus, king of Ithaca, famed for cunning. The Greeks pretend to withdraw and leave a wooden horse at Troy’s gates as an offering to the gods, hiding their bravest soldiers inside. The Trojans bring the horse into the city and celebrate.

When night falls, the hidden soldiers emerge and open Troy’s gates to the Greek army waiting outside. The city is sacked, and the account emphasizes mass killing of men and boys, including King Priam and Hector’s young son Astyanax, while women are taken captive.

Troy falls, and yet survival remains possible for some. Aeneas, identified as the son of Priam’s cousin, escapes with his elderly father, his own son, and a group of Trojans, a thread associated with Virgil’s Aeneid, and therefore not shown in this performance. The gift of the horse, the city’s joy, and the night conflict, however, are described as being conveyed to the audience with particular clarity.

Even with Hector dead, the story continues. Troy has not fallen, and allies still arrive, some from far away. The Greeks, aided by Achilles, defeat both the Amazons and the Ethiopians led by King Memnon.

Achilles then dies at the hands of Paris, the same Trojan prince whose actions began the war. The narrative offered the well-known explanation of Achilles’ vulnerability: Thetis dips her son into the River Styx, whose waters protect whatever they touch, but she holds him by the heel, leaving that spot dry and exposed, and Paris strikes him there.

The production also drew parallels between the Trojan War and the Gallipoli Campaign (the Canakkale War), suggesting that although they were fought in different eras and between different peoples, both conflicts produced consequences that outlast their own time.

For Anzacs, steep slopes and Turkish trenches above them can read like Troy’s unbreakable walls in this interpretive frame. Another cited example is poet and veteran Patrick Shaw Stewart, whose poem “Stand in the trench, Akhilleus” references Book 18 of the Iliad and expresses an identification with Achilles’ pain after losing Patroclus.

In the performance, Gallipoli references are delivered via spoken narration at the beginning and end, while the finale pivots toward peace messages, reinforcing the idea that the Troy epic has been presented for 18 years through Fire of Anatolia with an Anatolian perspective.